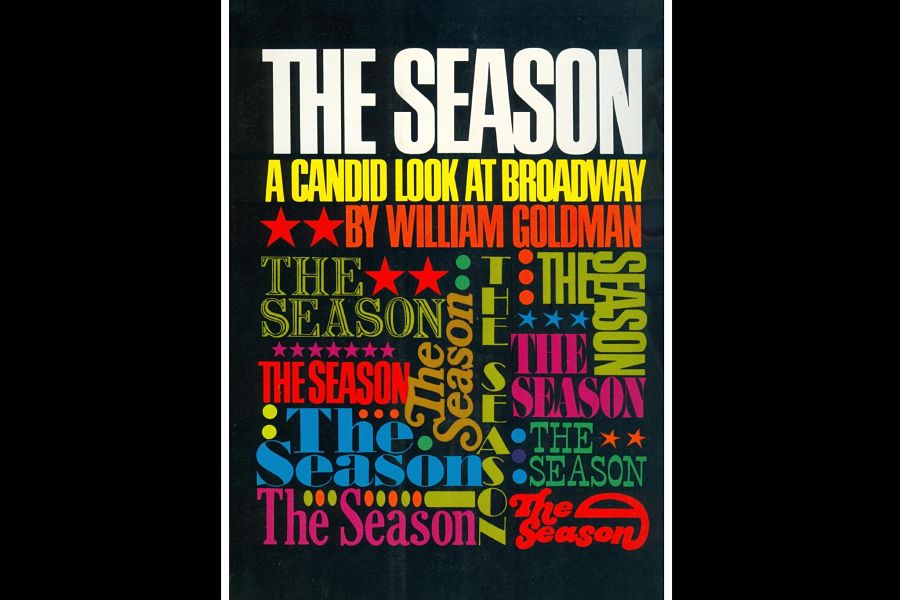

When American Theatre asked me to write an appreciation of William Goldman’s The Season: A Candid Look at Broadway, I thought, oh, what a welcome chance to dip into that book again. Structured around, and telling the story of, every show that opened on the Great White Way in 1967-68, The Season is my favorite book about the theatre—as gossipy as John Houseman’s Run-Through, as passionate as Peter Brook’s The Empty Space, as perceptive about theatrical craft as Moss Hart’s Act One. When Goldman died last week, most mourned him as a mensch, or as a novelist-turned-screenwriter (it’s hard to top a résumé that includes The Princess Bride, All the President’s Men, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid). But over here in the theatre-kids section, we mourned him for The Season.

And then…I couldn’t do it. There is no dipping into The Season. The only option when you pick up The Season is to read all of The Season, cover to cover, from its first bitchy account of a Judy Garland concert to its prudish account of Hair, in which Goldman tears his own hair out at the sight of a naked penis. It’s frank and revealing, not least about the mind of a 36-year-old writer who has recently co-written a not very successful musical with the great John Kander. In some sections, he writes with the cool-eyed interest you get from a participant-observer-anthropologist. But the book is mainly filled with the wonderfully stung opinions of a man who still felt the sizzle of being in the game. Goldman denounces director Mike Nichols as “brilliant and trivial and self-serving and frigid” in his “Culture Hero” chapter, because he doesn’t like the way Nichols accepts an award and he can’t bear how good Nichols is at staging offstage dialogue. Ah, human nature: Irrational loathing is still the greatest tribute one theatre artist pays another. (This is the chapter where I physically hugged the book like a friend.)

Goldman’s book draws you onward, laying cookie-sized crumbs for you along the path. How could you stop after the chapter on theatre sadists who giggle at a curtain bonking a Treasure of the American Theatre on her head? Could anyone read the account of how George Abbott (then helmer of 110 Broadway shows) behaves in rehearsal, then just close the book? Trick question—no one could do that. But if you’re too busy to fall down this particular rabbit hole, and while you wait for your copy to arrive at your local bookseller’s (visit the Drama Book Shop while you still can, New Yorkers!), here is a brief and biased list of the takeaways from this weekend’s rereading.

Lesson One: Nothing Changes

It has been 50 years—time enough for change, you would think. But one reason Goldman’s look into the ’60s biz is so useful is that it’s a window that reflects like a mirror. In a bustling critical atmosphere, The New York Times is the only review that matters? You don’t say. The ticket-selling business is a suppurating evil that erects needless barriers between the audience and the show, the artist, and her profit? Sounds familiar. In a theatre press agent’s office, Goldman listens to them talking about “the proposed use of computers to get people theatre seats, thereby possibly cutting down on illegal ticket speculation.” Would that make any difference to the theatre? “I don’t see why,” the press agent says. “We’ve created dishonest people; we’ll create dishonest computers.” Mirthless laugh.

Lesson Two: Data Is a Drug

The most exciting part of Goldman’s book isn’t the interviews (not even the heartbreaking one with Tennessee Williams, who feels the whole world is against him) nor even the exquisite cattiness. It’s the metrics. Goldman commissioned a theatregoers study from the Center for Research in Marketing, and salted through the book are cold, hard numbers about who comes to the theatre, why they come, and what they’re looking for. His last chapter, “What Kind of Day Has It Been?,” crunches those numbers—charting the commercial theater’s increasing revenues and declining attendance, the amount of money lost on shows (you can hear the drumbeat coming for non-musicals on Broadway), and the death of the walk-in business. The single headiest finding: When people were questioned about what they thought “Broadway was actually like…the only word that came close to satisfying them was ‘light.'” He goes on: “Almost half of the New York goers wanted the theatre to be important, while barely 10 percent thought it was.” We’re in the age of sabermetrics and search engine optimization, but the clarity of this 50-yaer-old study still feels revolutionary.

Lesson Three: Critics Are the Absolute Best

Oh ho, I surprise you there. You have perhaps heard about the section in which Goldman calls critics “failures as people” and “putrescent.” You have, if you’re lucky, read his scalpel-sharp dissection of the Times then-chief critic Clive Barnes, and you have (even if you despise critics) bled a little sympathetic drop for Barnes as Goldman carves him into dog food.

But there are two things happening over the course of Goldman’s long year in the plush seats. First, the book itself is a mash note, in code, to all those slogging souls who go to everything. Goldman makes us feel the hard labor of writing the book: He dramatizes his wild-eyed fear for his life and sanity at Leda Had a Little Swan; he tells us about the tornado of garbage sex comedies like There’s a Girl in My Soup! and How Now, Dow Jones that people were pitching in the late ’60s. As we sympathize with him for surviving a year of that dreck, we spare a sudden kind thought for all those critics who do that every year, with no book contract giving them a helpful push.

Second, and as every critic knows, Coverage Is Advocacy. There’s no more loving gesture than paying very, very close attention to something, and that Barnes chapter—read in a certain light—is a thorny bouquet.

Lesson Four: Your Hero Will Disappoint You

This is the hardest stuff to grapple with—I have encountered people who feel that Goldman’s attitudes toward gay artists poisons the entire book for them. Without a doubt there’s offensive, blinkered stuff in here. What apologia can I offer? There’s the “man of his time” argument, or there’s the close reading you could do, showing that for every time he calls same-sex love “unsettling” he also calls for more frankness, more candor and bravery in producing gay work. His outrage at the play Staircase is actually about the feeble, pandering gestures of the production team and performers, who all suddenly felt the need to talk about their wives and children in their bios. That kind of nonsense is still happening. But really, if you’d like to have the curated experience, skip the chapter called “Homosexuals” and pages 127-129. That’s what I did this time around, and I fully recommend.

Lesson Five: God, Theatre Is Hard

If you are not stupidly, stupidly in love with the theatre already (you are already reading the American Theatre website, which…welcome, my people), you will be after reading this book. Most of the book is about work. You certainly get a contact high from how much work went into it—the 1,000 interviews, the investigative work, the nights at the theatre. And Goldman, in turn, is getting his thrills from the proximity to other people working as hard as they can. He writes about how hard an actor works to get the role of a lifetime—which then does nothing for his career. He writes about the no-pretension-allowed labor of working on shows out of town, with great minds like George Abbott and Jerome Robbins and Hal Prince and David Merrick all trying to fix something that won’t be fixed. He conveys, across these 50 years, the sheer heat of time invested, brains whizzing, bodies sweating in service to a show.

On this reading, it actually reminded me of going down to Florida to watch a rocket go up at Cape Canaveral. Even at failed launches, the tower goes through its setup: everything shudders and roars; gouts of flame and steam and fuel pour down; the whole world vibrates. Read Goldman’s book—and it’s like suddenly transporting to the theatrical launchpad. Not every show takes off, sure, okay. But you’ll want to feel that power all the same.