White Oak plantation, home to pine stands and palmettos, is located in a muggy small town in Florida. The property, which sprawls across more than 7,000 acres, was the project of Howard Gilman, a lumber and paper magnate. (It was later run by the Howard Gilman Foundation before it was sold in 2013.) Gilman, a supporter of the arts, built a dance studio for his friend Mikhail Baryshnikov; hosted playwrights from the Sundance Institute; and invited composers, actors, and musicians to his property to work. Gilman was also an animal conservationist, once sending a zoologist to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) to capture a rare okapi. Before being sold, the plantation was home to 270 endangered animals.

Gilman wanted to conserve the endangered. For him that meant both animals and the arts.

It was fitting then that in 2003, the Theatre Communications Group (TCG) convened its first Theatres of Color Gathering at White Oak Plantation. For three days, 21 theatremakers from Asian Pacific Islander (API), Black, and Latinx theatres met and talked about the needs and challenges of running theatres of color.

Artists and theatres of color have long been endangered. The 2003 gathering included a fiscal survey of 19 of the theatres present: TCG compared these theatres of color with Group 1 (budgets of $499,000 and less) and Group 2 (budgets of $500,000 to $1 million) nonprofit theatres across the country. The survey showed that while the theatres of color were productive, staging more than 110 productions, funding was a problem. Theatres of color relied more than white theatres on single-ticket sales for income; usually had no endowment, interest, or capital gains income; and had low rates of board and individual giving.

“Theatres of color have always pretty much lived on really thin margins,” says José E. Gonzalez, who came to the 2003 White Oak meeting as the executive director of Oregon’s Miracle Theatre Group (Milagro). “It doesn’t take a lot to tip you in the wrong way.”

But issues raised in 2003 went beyond funding. Theatremakers also felt they had to constantly justify their existence and explain their cultural perspective to outsiders. According to the report produced after that White Oak convening, the media, public and private funders, and educational institutions all failed to adequately understand or credit the “generative role played by theatres of color” in U.S. theatre. Critics often treated the work as an afterthought.

Given these special challenges, bringing together the theatres of color for that first convening was “momentous,” according to Gonzalez. “It was an acknowledgement in a big way that theatres of color exist and that we are a viable force to be reckoned with.”

Fifteen years later, Gonzalez, now executive director of Milagro, and a handful of others from that White Oak meeting convened again. This time, 47 theatremakers and individual artists of color attended the gathering, held in St. Louis in June 2018 as a pre-conference to TCG’s annual conference. They found that while many aspects of being theatremakers of color were the same as before, the assembled artists also realized they had a lot to celebrate.

New Alliances

When TCG staffers Elena Chang, recently promoted to be director of the organization’s EDI Initiatives, and Emilya Cachapero, director of artistic and international programs, started working on another major convening of theatres of color, they saw that the landscape had altered dramatically since 2003. One of the biggest changes was the development of collectives of color.

Almost immediately after the 2003 gathering, the six API companies that had been there created the Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists (CAATA) and hosted the first national Asian American Theatre Conference in 2006, followed by a performance festival in 2007. Now the performance festival and conference are rolled into one event colloquially called ConFest.

Mia Katigbak, artistic and producing director for National Asian-American Theatre Company, was at the White Oak gathering, and remembers the impact that seeing the other API theatre companies had. “We had never been in a room together,” she told American Theatre in 2016. “As we talked, we kind of thought, boy, we should really think about getting together in something similar to that convening.” She helped found CAATA and is currently a board member.

In 2012, playwright Karen Zacarías and eight other Latinx theatremakers came together at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., to create the Latinx Theatre Commons (LTC). The group aims to increase the visibility of Latinx theatremakers, and organized the first LTC National Convening in 2013.

“We work on collectively gathering resources,” says Abigail Vega, producer at LTC. “We define resources as space, as contacts, as food donations, as plane tickets. More knowledge is our biggest resource that we collect together.”

The commons, which is not a dues-collecting organization and represents around 3,400 people, recently organized the 2018 LTC Carnaval of New Latinx Work in Chicago. It featured readings of six new plays and gave the playwrights a chance to develop new work with a Latinx creative team, including a director, dramaturg, actors, and designers.

The Black Theatre Commons (BTC) is the youngest of the groups. According to David D. Mitchell, program manager for BTC’s programs and development, the group has been in talks and meeting since 2013, but officially formed in 2017.

“BTC started off as an affinity group at TCG conferences, and before that affinity group, Black practitioners and administrators had been meeting around the water cooler at each one of these conference for years having the same discussions about sustainability in Black theatre,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell describes BTC as an advocacy organization focused primarily on brick-and-mortar Black theatres. Recently BTC received funding for its first initiative: archiving the history of America’s regional African American theatres. According to JaMeeka Holloway-Burrell, program manager of logistics at BTC, the commons is hoping to also develop programs to help Black theatres with capacity building, offer aid to students in university theatre education programs, and create more mentorship opportunities.

“We want to make sure that the field is strong, so when future generations are up and coming they actually have a playing field,” she says.

In addition to being in conversation with members of each theatre-of-color collective, which represent the three groups that formed at the 2003 convening, Chang and Cachapero also reached out to Native American and Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) communities.

Indigenous theatremakers don’t have a commons, but in 2015 Larissa FastHorse, a Native American playwright, and Ty Defoe, an Ojibwe and Oneida performance artist and activist, created the cultural consulting firm Indigenous Direction. Jenny Marlowe, the firm’s artistic associate, helped TCG find Native and Indigenous theatres to invite to the gathering. As a result, this TCG pre-conference and conference had the most Indigenous theatremakers ever in attendance.

“I think to a certain extent, the Indigenous population has always been a bit invisible,” Marlowe says. “There are a lot of people out there in America who don’t even know Indigenous folks still exist. But in recent years there is a resurgence of Indigenous identity, Indigenous theatre and performing arts. This is just a really exciting time.”

Catherine Coray, program director for the Middle East U.S. Playwright Exchange at the Lark and a faculty member at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, says the MENA community doesn’t have any official commons or advocacy group, though she and some others are working toward it. She organized the first MENA gathering in 2007.

“It was literally eight people sitting around a table,” she says. She worked with Torange Yeghiazarian, executive artistic director of Golden Thread in San Francisco, to continue hosting gatherings. By 2012, there were 40 people in the room, and in 2016 there were 75 artists from across the country at the meeting.

“It was really inspiring,” says Coray. Three theatres—the Lark, Golden Thread, and Silk Road Rising in Chicago—started a playwriting fellowship, the Middle East America Initiative, to nurture a playwright of the Middle Eastern diaspora. After awarding it to three people, the fellowship went on hiatus and should be accepting applications again next year.

Coray says that one of the things she’s been most passionate about, in addition to bringing MENA theatre artists together and raising money for the fellowship, is getting plays translated “in both directions,” i.e., translating plays by U.S.-based artists into Arabic and getting Middle Eastern playwrights translated into English.

“There’s a kind of expectation that any art work from that part of the world is necessarily going to be about war and conflict and what we see in the headlines,” says Coray. “But of course what we’ve been finding is that the plays I’m identifying with are telling stories just of life and identity and relationships.”

In speaking with various theatre artists, Chang and Cachapero discovered that while grassroots organizing within a given community helped its members feel more connected to one another, there was a desire for more communication among the groups.

“One thing that seemed to be missing was this arc where folks would be able to connect with each other,” says Chang. “And part of our work with bringing this gathering together in June was to see where folks have been and to really understand more of the similarities, the complexities, the differences among the different communities within the theatres-of-color ecology.”

When conversations began in January 2018, Chang and Cachapero weren’t sure how many theatres they would be able to bring to the convening. They were hoping maybe 15, but as they secured funding, that number quickly rose.

“We worked very quickly to create a system where we could bring as many theatres of color from across the country,” Chang says. “We were thinking about artistic differences, years that they were founded. We were also looking at balance of representation, because we noticed that there were significantly more African American, Latinx, and Asian American theatres across the country than Indigenous groups.”

With research and the help of the different collectives, TCG identified 165 theatres of color, and sent invitations to 85 artists and companies. In total, 41 companies were represented as well as 6 individual artists—more than double the number of theatremakers at the 2003 convening.

Meet Me in St. Louis

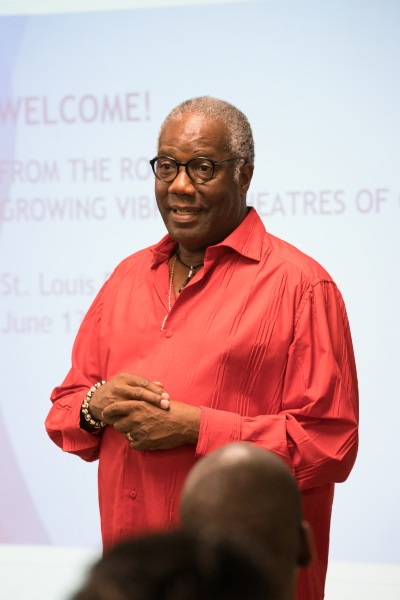

On a steamy Wednesday in June, the parking lot in front of the St. Louis Black Rep’s offices was nearly full. Inside it was even more crowded, as theatre practitioners from all over the country grabbed lunch and name badges for the Theatres of Color Gathering. While TCG has hosted gatherings for theatres of color since 2003, this was only the second major one. It was both larger and—at six hours—longer than any since White Oak.

It was rather poetic that the Black Rep played host. The Black Rep’s founder and producing director, Ron Himes, was part of the reason for the first convening. In 2001, Himes called Ben Cameron, then executive director of TCG, and asked, “What is TCG doing for African American theatre companies?”

Recalls Himes of that call, “TCG is the major service organization for the field. They have the ability to be advocates. My hope was that they would somehow facilitate a conversation that would move beyond talking about technical assistance and move to helping us get more access and build relationships with the philanthropic community.”

The events of Sept. 11, 2001 delayed the initial convening, which in any case didn’t turn out to be quite what Himes had envisioned. It included more than just African American companies and wasn’t focused on improving ties with the philanthropic community, but instead offered theatres of color the chance to network and discuss fiscal, organizational, artistic, and technical challenges.

The aim of the 2018 meeting was similar: to offer people a chance to connect. Theatremakers had nearly 90 minutes to chat over lunch. By way of introduction, moderator Khanisha Foster, associate artistic director of 2nd Story, asked people to share what song would play if they were cracked open.

“I loved hearing about everyone’s song—I want that playlist,” says Randy Reyes, artistic director for Theater Mu and a member of the CAATA board. “To me the initial introductions were a moment when I could take notice of the beautiful diversity in front of me, not only in terms of ethnicity but also in experience and focus and expertise and spirit.”

After discussing some theatre history with each of the groups in the room and hearing from several people from TCG about the impetus behind the convening, a representative from each collective or affinity group gave an update.

“One of the things that inspired me about the gathering was to get in a space with the Black Theatre Commons and the Latinx Theatre Commons and CAATA, because we don’t have anything official like that,” says Coray. “I think it galvanized those of us who were there to want to make that happen sooner so that other groups would be able to reach out to us and have an idea of who makes up this affinity group of Middle Eastern American theatre artists.”

Next Foster got the group talking.

“Tell us a moment in the theatre when, as an audience member or a participant, you were moved to turn your magic all the way up,” she said. People shared stories at their tables and distilled what they’d heard into just a few words, which were then collected. Words that emerged included “community,” “representation,” “revelation,” “recognition,” and “energy.”

“This is why we do theatre,” Foster said.

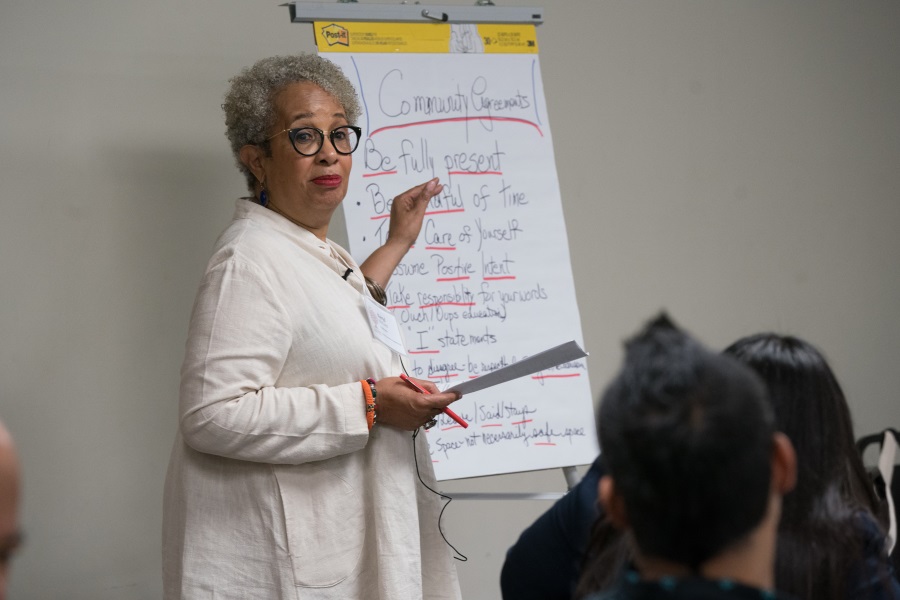

Co-facilitator Keryl McCord, president and CEO of Equity Quotient (EQ) and one of the founders of the arts organization Alternate ROOTS, pointed out a word that wasn’t up there: grants. “There’s a disconnection between why we do theatre and how it gets done,” McCord said. “We need to talk about the 800-lb. gorilla in the room: funding.”

McCord cited the 2017 report “Not Just Money: Equity Issues in Cultural Philanthropy” by Helicon Collaborative, which found that 58 percent of all foundation funding goes to arts organizations with budgets of $5 million or more, despite the fact that arts institutions that size make up only 2 percent of all arts and culture organizations. More to the point, across the country there are fewer than 50 cultural organizations serving people of color that have enough funding to maintain a $5 million annual budget. The study also found that just 4 percent of all foundation arts funding is allocated to arts organizations that serve communities of color.

“These numbers tell us scarcity is real,” McCord said. But given the constraints and goals of the meeting, McCord took funding off the table that afternoon. “We all know it’s an issue, but we don’t do theatre for grants,” she said. “Liberation will not come from a grant.”

“I’m glad they took money off the table so we could dream,” says Leilani Chan, founder and artistic director of TeAda Productions.

Marlowe agrees. “As important and complicated as funding is, I know that there are ways to support each other using our own voices collectively, rather than haggling over the funds that we’re competing for.”

But others were disappointed that the money talk was cut short.

“Funding should have been part of our conversation,” says Himes. “I feel like there should have been funders in the room. Yes, we can have these conversations, and yes, all of our theatres of color do tremendous work and have done tremendous work with limited resources. But it was an opportunity for us to have some access that many of us are not able to get on our own, and I just felt like that opportunity was missed.”

Gary Anderson, producing artistic director for Detroit’s Plowshares Theatre Company, agrees. “Money is not the whole picture,” he concedes, “but money communicates where our strengths and weaknesses are.”

He also thinks that not discussing funding skirted another complicated issue. “For us to be successful at what we came together to do, it is going to cause harm for the larger community, and we need to be aware of and comfortable with that,” Anderson says. “Because if the pie is this big, and they’re getting 58 percent of it, for us to be doing better means that we need more, which means that they have to get less. That’s just the reality.”

For her part, McCord went on to discuss the nature of U.S. institutions and the ways they support white supremacy. The lack of funding for theatres of color, she said, is actually how the system is designed to work. “It’s important that we understand that in the arts, the predominantly white institutions are the result of the systems working just fine,” McCord said. “They are designed to support the status quo.”

In 2011, Helicon Collective did a similar study of arts organizations and found that 55 percent of arts funding went to organizations with budgets of $5 million or more. Despite funders stating a commitment to diversity and equity, the 2017 study showed that the numbers actually got worse.

“What does white supremacy bring to the table?” McCord asked. “It brings the table.”

McCord paraphrased Adrienne Maree-Brown—an editor, activist, and facilitator—who said that social justice work is like science fiction, because we’re trying to create a world that doesn’t exist. Still, she insisted, “It’s vital. It’s on us—it’s our job to do.”

So she asked the room, “How do we organize? How do we plan? How do we agitate to create a different future for ourselves and our communities? Anything we want to achieve, we can do it together.”

A Way Forward

The meeting then turned to focus on developing action items to help others in the room. People started out having one-on-one conversations, then broke into group conversations, and finally broke out into their affinity groups.

“When we were breaking up into theatres—Black theatres, Asian American, Native American, Arab American, and Latinx—I had a little bit of inner turmoil there,” recalls Moses Goods, artistic director for ‘Inamona Theatre Company. “I was there representing Native Hawaiian theatre, but I’m also half Black. I thought, where do I go? Where would I feel most comfortable going? And right as I thought that, someone yelled out, ‘Well, what about those of us who are Mixed?’”

Foster encouraged those who identified as Mixed Race to start their own table. It was one of the biggest in the room. “That to me was the most valuable thing about the whole convening,” says Goods. “We were able to sit together and talk about being Mixed Race. And that’s America, really—a large part of America. We’re not just one race. We’re a number of things.”

Kyoung Park, founder and artistic director of Kyoung’s Pacific Beat and the first Korean playwright born in Latin America to be produced and published in the United States, agrees that forming the Mixed Race space was transformative.

“It was the first time I felt that I could be in a space with people of color and not have to force myself to be in one specific space or another, but actually have the ability to be with other people who felt like they belonged in multiple spaces, and yet at the same time maybe no space.”

The group remains in touch and wants to continue its conversation at future conferences. Goods hopes that forming a Mixed Race alliance can act as a bridge between the existing affinity groups and also push the issue of intersectionality in the theatre community.

Chang says that TCG hopes to work further with Mixed Race theatre artists, saying that the development of this affinity group was one of the biggest things to come out of the gathering.

The now six affinity groups—Black, Latinx, Asian Pacific Islander, Mixed Race, Middle Eastern and North African, and Indigenous—worked to develop six action items. The subsequent discussions proved fruitful, participants say.

“Other things came up in our conversations that were unexpected, that didn’t have to do with the action steps, but were revelations about what perhaps we needed to do next to strengthen the community that we came from,” says the Lark’s Coray.

Seeing everyone working together to figure out ways to help one another was powerful in itself for Khanisha Foster. “I’ve never seen affinity spaces happen right next to each other like that,” she says. “I was really moved to see people go back to people in their communities and say, ‘Hey, we’re not just talking esoterically. The people we’re talking about building up are sitting across the table from us. They’re across the room. There are five other tables where people are talking about what they can do for us. What can we offer in return?’”

In the end, after making a lot of tough choices, the gathering hammered out a final six action items. There were:

- Open a call to a particular community, embracing intersectionality, for a collaborative storytelling project or story circle. Historically marginalized people would take the lead in a space of their own making.

- Organize another TOC meeting in NYC or another location, and/or convening for a pre-conference. Rotate meetings at theatres of color all over the country.

- Create a culture of inclusion by sharing resources, including events, social media, and websites.

- Arrange a call/initiate contact with your local organizations of color. Let the ripple effect keep extending.

- Challenge organizations to create a Mixed Race space of real conversations informed by the Mixed Race Bill of Rights with the clear end in mind that future audiences will be based on mixed racial identities.

- Identify affinity groups inside and outside your organizations.

Many participants say they were inspired by these action items.

“The item that resonated with me was just sharing each other’s events and projects through social media,” says Samson Syharath, co-founder and producing ensemble member of the Oregon-based Theatre Diaspora. “It’s a simple solution, but it helps us stay connected to one another.”

For Muriel Miguel, artistic director for Spiderwoman Theatre in New York, which focuses on Indigenous work, the action items opened up ideas for new collaborations. “We were talking about having readings of different Indigenous people,” Miguel says. “But looking at the room, I thought: We’re all different types of people of color. So it would be interesting to have readings from a lot of us.”

But others point out that the items were similar to ones that came out of White Oak, which included collaborating on storytelling projects or creating a culture of inclusion by marketing each other.

“I think a number of the action items, specifically in regards to collaborating on production, are things that we talked about before,” says Plowshares’ Anderson. “So these are not new. But it will be good if we act on them.”

At the start of the gathering, Himes mentioned that issues from White Oak were still on the table today. He hoped that the gathering would help change that, but “as in the past, many of those action items need funding,” Himes says. “They are very motivating and inspiring and galvanizing. But ultimately, the big question is, how do we get the resources that we need to accomplish them?”

The way forward to an answer wasn’t entirely clear by the end of the day. But as people started to clear their tables and help clean up, conversations spilled out into the hallway and in the parking lot. People who had been strangers were connecting on social media and sharing rides back to the hotel.

“What I realized during the gathering was that so much of what we are all talking about in our own affinity spaces is the same,” says David Mendizábal, producing director of New York City’s Movement Theatre Company. “I liked coming together to embrace that we are writing our narratives collectively, not just individually.”

Still, he adds, “I think there’s a lot more work to be done, and obviously once every 15 years isn’t enough. I don’t know that once a year is enough.”

A Test Case of Solidarity

That evening everyone reconvened, this time at UrbArts, a venue in St. Louis’s North St. Louis, a historically Black part of town. UrbArts also supports youth and community development programs. The event featured works from local St. Louis artists, poets, and dancers. But the main draw was the chance to cement the friendships and bonds that had been started at the Theatres of Color Gathering.

“I was really proud of how the arts showcase happened in the evening, because it was a way to highlight local St. Louis artists as well as celebrate a very long, intense session with leaders of color,” says Chang. “It brought me joy to see folks like Jackie Taylor [founder and CEO of Black Ensemble Theater] and Woodie King [founder of New Federal Theatre] coming together, connecting.”

For many, this was their last chance to catch up with old friends or solidify new connections. Many of the theatremakers at the gathering did not stay for the subsequent conference, either due to work commitments or monetary constraints.

But for those staying and others just arriving, the work was just beginning. Just two days later the TCG conference would offer an early, and to many unexpected, test case of the bonds formed at the day’s gathering. But first, one day into the conference, the leaders of theatres of color met over breakfast to further refine the action items they’d produced at their gathering, as well as include in the discussion artists who could not attend the pre-conference.

Foster and McCord moderated the breakfast. Since it was just a little over an hour, things went quickly. After introductions, Foster and McCord called for a share-back where people who had been at the gathering could speak about the highlights.

“We wanted it to be in their words rather than us telling them what had happened,” explains Foster. They also put up a piece of paper with the words “cultivate abundance” as the theme for the day. McCord once again shared some background about funding disparities.

The main aim of the breakfast was to discuss the six action items from the gathering. The idea was not only to get feedback from people in the room, but also to make the action items more concrete, to discuss how some of the ideas would look when folded into the day-to-day work of running a theatre.

“That was one of the most exciting parts of the week,” Foster says. “It was a yes-and situation. There was a lot of building in terms of, how do we create space for each other and how specific can we get?”

People discussed, for instance, how promoting other theatres of color on social media would look. Was this going to happen once a week? Once a month? Which day would it be? Other people suggested entirely new ideas, such as having theatres host scholarship sessions for youth of color to teach them how to apply for scholarships.

Other ideas were to support people of color trying to get into master’s programs for theatre, to explore connections with HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), and to better support the leaders of theatres of color. Another idea was to help theatremakers hold their own organizations accountable. White supremacy could be internalized and manifest itself as homophobia, misogyny, and, of course, racism.

“People were like, ‘This is a great first draft, but here is what I really need,’” says Foster about the feedback.

For Foster it was exciting. But McCord says it was a difficult breakfast to moderate.

“You’re not giving voice to the people who are new to the room,” she says. “And at the same time, you’re not doing justice, full justice, to the people that you were with for more than half a day. It turned out okay—it was good. But there’s this sense, to me, of the necessity of giving time, full time to these really important, momentous gatherings.”

Something truly momentous happened toward the end of the meeting, when Foster remembers being handed a piece of paper that mentioned something about yellowface at the latest production of the nation’s largest and oldest outdoor theatre, the Muny. The Muny, which was staging Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, also happened to be giving free tickets to conference badge holders.

“We asked people in the room who knew what was going on to speak to it and then we adjourned,” Foster says.

A Step Back to Bring People Forward

Word about yellowface at the Muny spread quickly. People found out via social media or word of mouth, and plans for a protest were formed. In Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, a revue featuring some of the choreographer’s most well-known dances, actors in the show play multiple parts; and in a scene from The King and I, Tuptim, an enslaved woman from Burma, was played by a white actress.

While this did not seem like an egregious transgression to some, such representational choices continue to make people of color invisible, and indeed in many cases literally unemployed. To understand the thinking behind the protest that would soon take place at the Muny, it’s important to consider the points of view of some who gathered at the Theatres of Color Gathering.

For one, says Theatre Diaspora’s Syharath, when he was younger he “thought theatre wasn’t for me—I felt like theatre was for white people,” in part because he rarely saw anyone who looked like him onstage or in the audience.

And when Randy Reinholz first started staging plays as artistic director for Native Voices at the Autry, he found himself in a Catch-22, which was that he was repeatedly told “there weren’t any Native playwrights, because there weren’t any Native actors to play the roles, and there weren’t any Native actors, because there are never roles for them to play. So we had to get rid of that self-fulfilling paradox and start demonstrating that the work is there.”

According to a 2017 study by the Actors’ Equity Association, female actors and stage managers and actors and stage managers of color get fewer Broadway and Off-Broadway jobs and often wind up in lower-paying positions. That diminished opportunity for people of color was on full display at the 2018 Tony Awards, according to Plowshares’ Anderson.

“People patted themselves on the back for inclusion because an Asian American actress was nominated for a role in Mean Girls and a Black man was starring in Carousel as Billy Bigelow,” he says. “That’s not real inclusion. Real inclusion is me being exposed to Native work from their own voice and Asian American work from their own voice. Not somebody in a show that was originally written for a white actor. That’s not going to change our appreciation or understanding of one another’s cultures.”

Armed with this sense of representational inequity, about a dozen protesters headed to the Muny, Leilani Chan among them. It was her first time at the Muny, which, with 11,000 seats, feels more like a stadium than a theatre. From the start, she says, it was unsettling.

“They sing the national anthem before the show,” she says. “So just the pressure of, do I put my hand on my chest? Do I take a knee? Do I not participate? I was already feeling greatly outnumbered by the general whiteness of the audience. So I thought, if I take a knee, am I putting myself in a vulnerable position?” She settled on a neutral stance, but “before the show even started, I was keenly aware I wasn’t in California anymore.”

Chan was equally disappointed that Mike Isaacson, artistic director and executive producer for the Muny, offered no context in his opening remarks.

“I get that we’re trying to historically recognize the choreographer in these musicals, but not to bring a contemporary lens to that…” Chan trails off. “I see those representations of Indigenous people and immigrants as directly connected to headlines right now, as children are incarcerated trying to cross the border. It’s these historical images and stereotypes that allow people to think of people of color as inhuman.”

The show included not just yellowface but also redface, as sailors danced around in Native American headdresses and plastic hula skirts and leis, and brown face, when many Puerto Rican characters from West Side Story were played by whites. Though the redface came first, the TCG protesters waited until the King and I scene before they began booing and shouting “no yellowface.” Security asked them to leave the theatre and they peacefully complied.

“It is very overwhelming to be in a theatre with 11,000 seats and know that this work is happening and it’s been happening and no one has said anything,” says Reyes. “There was a feeling of helplessness.”

By the next morning video of the protest had already gotten 20,000 views, and a social media firestorm had begun. Protesters and others gathered at the Theatres of Color Working Meeting, watched the video, and discussed what they’d witnessed. “It wasn’t until that meeting that we realized we had to draft some kind of statement,” says Chan.

Several people from different affinity groups started drafting a statement, while others kept working on what had been started at the Theatres of Color Gathering. They kept chipping away at how theatres of color can help each other.

“I said at the working meeting, ‘We came here to get some things done, but now we’re having to respond to this,’” Chan says. At the time she was frustrated. “But that is the work. We have to politically respond to something that’s going on at a major institution. Meanwhile, we’re not taking care of our small organizations.”

The attention of the meeting was divided. A few ideas emerged in relation to the action items from the gathering: to send out a survey to assess each theatre’s capacity and how much help they can offer, and to use the group hive mind to help map theatres of color across the U.S. But the rest of the energy in the room was focused on the statement about the Muny protest. Artists from every affinity group were pitching in.

“I have never seen people organize so quickly,” says TCG’s Elena Chang. “But this happened during one of the strongest programming arcs we’ve had specifically for theatres of color and people of color. So if anything, it just felt like a moment to catalyze. POCs that I spoke to were just really empowered.”

Foster, who moderated the meeting alone, was also impressed. “It wasn’t just one community saying, ‘Hey, this is not okay. It’s very hurtful.’ It was all of us across communities saying, ‘Hey man, I got you.’ And I think that’s an important part of how we create change. Instead of being divisive, we build together.”

The plan was to present the statement at one of the conference’s afternoon sessions, How We Move Forward. There theatre artists of color would explain why the situation was hurtful, read the statement, and show the video “Beyond Orientalism.” Online a flurry of messages asked as many people of color to show up to the session as possible to offer moral support to those speaking out.

That afternoon the room was full, and about two-thirds of the people were white theatre professionals. Members of different affinity groups explained why yellowface, redface, brownface, blackface, and cripface (casting a non-disabled actor for a disabled part) are wrong.

“These are not acceptable ways to deal with any material, no matter how it was done when it first came out,” says Marlowe. “An argument that I heard a lot is, ‘But that’s the source material. That’s the way it was written in 1951.’ That’s never an excuse. It wasn’t okay then, and it’s not okay now.”

Native American playwright Larissa FastHorse talked about how feathers in a headdress are earned via good deeds and acts of bravery, and that one headdress could have feathers from generations of family members, each feather a story of an accomplishment.

“Imagine someone taking that beautiful physical representation and putting it on as a joke and dancing around in it with the intention of making people laugh at the ridiculousness of it—laugh at your family, your ancestors, you,” FastHorse said as people began to audibly tear up. “Now imagine being in a theatre surrounded by thousands of people laughing at that history, turning your loved ones and their life accomplishments into a joke.”

When members from each affinity group stood up to read part of the statement that had been drafted earlier that day, they invited others in the room to stand in solidarity. The entire room rose to its feet.

Just a week after the conference, CAATA drafted a more formal statement and published it online. It garnered hundreds of supportive signatures.

“My takeaway from the experience was the need to organize,” says Kyoung Park, who helped draft the statement read at the conference. “I think it is becoming clearer and clearer that us being isolated in our own regions can be ameliorated by organizing at a more national scale.”

Adds Marlowe, “We found a great amount of collective strength in that moment.”

The moment also reaffirmed that the work theatres of color do remains just as critical now as it was 15 years ago. But now more than ever, theatremakers of color are stepping up and demanding to be heard.

“We are living through a moment where people are feeling empowered to use their full voices and bring all of themselves to the table,” says Marlowe. “And in the midst of everything terrible that is happening in the world around us right now, that is something I actually find very encouraging. We are hearing a lot more stories that we may never have ever known were out there. And we need those stories. We can’t find common ground until we hear each other’s stories in each other’s full and authentic voices.”

Takeaways

Theatre professionals who were able to convene for the Theatres of Color Gathering took away a lot from the experience. Here are some of them.

“The gathering felt like a moment and an opportunity to really build a much stronger collective movement across our different communities and theatre organizations. And that was surprising in a very positive way.”

—Kyoung Park, founder of Kyoung’s Pacific Beat

“I think now it’s up to us to keep up those connections and push it further. I’m involved in a process right now where we have to consider which director would be working on a project. I said, let’s go to the African American and Latinx community and see if somebody is available there first. I’m fully intending to do some joint playwriting work when I can find a playwright or a collaborator outside of my community.”

—Heather Raffo, Iraqi American playwright and actress

“The biggest benefit of the gathering is feeling like you’re not working in isolation. A lot of us, we work in our little silos. The other benefit was to see all of the young people ready to go.”

—Randy Reinholz, artistic director of Native Voices at the Autry

“It was a good start. As the representative of the Black affinity group, I’m really glad that these other groups are stepping up and demanding some of the same things that we are as far as equity and resources are concerned. I think it’s timely. And I think that for us as BTC members, we’re looking at it as a two-part thing. We have a lot of work to do within our community and a lot of work with other community groups at the same time.”

—David Mitchell, program manager, Black Theatre Commons

“I want people to know how much thoughtfulness and joy is in the room when we gather. I think people might feel like, what is this secret space? But what it is is a lot of people who care deeply about their craft, who have dedicated their lives to it. And who are lifting each other up, and it’s a really magical thing to be a part of, and I’m grateful for that.”

—Khanisha Foster, associate artistic director, 2nd story

“I’m longing for the time when we’re not a pre-conference and we are in the conference, because quite frankly, the rest of the conference was not nearly as exciting or interesting to me as the pre-conference itself.”

—Leilani Chan, founding artistic director of TeAda Productions