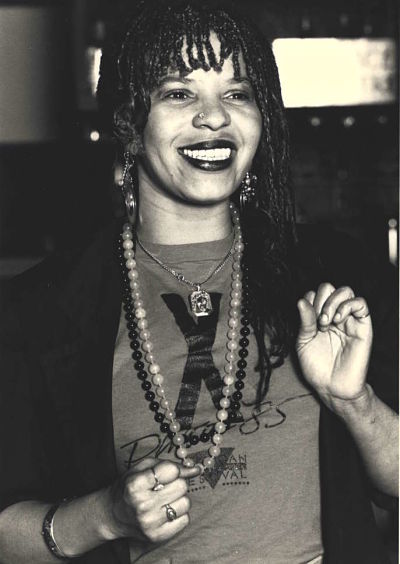

Playwright and poet Ntozake Shange, a founding poet of the Nuyorican Poets’ Café, best known for the play for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, died on Oct. 27 at the age of 70.

Strong coffee with sweetened condensed milk, grits with salmon stirred in. Rinsing out a tiny stovetop percolator she brought to college, she advised: “The most important part in making good coffee is to start with a very clean pot.” Ntozake Shange, then the 18-year-old Paulette Williams, was very definite about anything she had to say. After this advice I would never have any old grounds lingering in the coffeepot’s basket to leave a burnt taste in the brew. In reality, Zake wrote about those lingering bitter tastes in our day-to-day rituals from the moment she decided very definitely to write poems. She did not clean that pot, and the first poems were no drafts, but a poet’s work.

These sweet and pungent treats fixed in a Barnard College dorm seemed funny to me, as I was the Southerner and she the Northerner. “Geechees,” she said. She had a wonderful ear for the declarative rhythms not only of her forebears in the South Carolina Low Country but from Bronx salsa halls, St. Louis rhythm & blues, waitresses hounded in Jersey diners. She had an ear like Zora Neale Hurston for the sounds of secrets passed down from Angola, Jamaica, or Texas.

Even then her stories had an extravagance one would not immediately trust but rang true in some metaphorical way. Like telling an interviewer that we met on campus when she was singing a tune by Thelonious Monk and I finished it. Monk always; singing, no. We were going to model Lorraine Hansberry’s cool brilliance but take up the law and be the next Thurgood Marshalls. She was then the most buttoned-down, carefully coiffed woman I knew, navy suits with matching pumps. She would have definitely gone before the Supreme Court looking like that, but her sudden style change as she entered her 20s would have meant showing up in court with her bracelets ringing and the mixed printed cloths that became the Shange style.

One night in 1967 we went in a snowstorm to Judson Church to see what I recall being the last performance of Amiri Baraka’s play Slave Ship: A Historical Pageant. Where we sat we were staring through the wooden bones of the hull of a ship. People just above us were forcing others onto the deck and down into the hold. Only brutal shards of English; most words heard were Wolof. They stopped the show when an actor broke a leg being shoved. We walked back to the subway quite silenced ourselves, knowing that half a play had done what our essays did not. We saw a lot of plays, joined a Sonia Sanchez workshop, printed a literary magazine, performed in churches in East Harlem, and then went to California, she to the South, me to the North—and neither to law school.

Even in 1976, as for colored girls was going to Broadway, when we were thrilled to see an Adrienne Kennedy work in rehearsal with Cecil Taylor, I’m sure it never crossed her mind that she would find her face plastered on New York buses and subway walls for writing a play. After that she could not go out without people stopping to thank her. “Somebody, anybody, sing a black girl’s song.” This is what they were thanking her for. It is the line I have seen most in posts from friends and admirers of Shange since she died. And she spoke out, loving us all “fiercely,” and reached out to people around the globe from the prescient moment she grabbed that passé term “colored” for the title of her first theatre work.

Poetry was her place in the world. Or, as she put it, “i live in music/live in it/wash in it.” In an era when everybody was a poet sometimes, she was a poet for all times. Her theatre work brought what she was doing in bars, and basements to theatres—raw, joyous poetic language, music, dance, and space to improvise, let things happen. It is what we do when we find ourselves on the edge of life.

Her searing second play, A Photograph in Black and White, peers into a relationship between two artists, characters new to theatre—insular young black people treading the hazards of intimacy. They were familiars who lived behind the closed doors of our culture, and they were innocent precursors to the fabulous, haunted people of Bill Gunn’s play The Black Picture Show. Spell #7 introduced a number of male voices after their sheer absence from for colored girls had caused a shock not caused by the commonplace of plays only about men. She adapted Brecht’s Mother Courage to a wagon crossing the Southwest and let Gloria Foster loose with Brecht’s ideas and Zake’s vernacular rhythms.

She wrote of black writers, “Until we believe in the singularity of our persons/our spaces, language & therefore craft, [we] will not be nurtured consciously.” She was pointing to a particular absence of interiority in black literature, drama, and film that has always been in the solos of our musicians. But following the spoken word artists whose work we memorized and who taught us, some literally—Langston Hughes, Amiri Baraka, Gylan Kain, Felipe Luciano, Pedro Pietri, and others—and in the enthralling company of Toni Morrison, Adrienne Kennedy, Alice Walker, Irene Fornes, Toni Cade Bambara, Sonia Sanchez, she showed us it was enough to learn how to take a solo, stand up and say your truth.

Becoming famous at 27 years old took away her privacy, the space needed to write. Strokes attacked her ability to walk. A neuropathy took the dexterity needed to use a keyboard. Yet she was still the smartest person in the room and easily the most determined. I thank her for calling to say her new ambition was to be a body building champ, for doing poetry readings the last week of her life because that’s what she wanted, and mostly for reminding us to stay at it. When asked what she would be doing for the rest of her life, she said, “I’m going to be writing poems, what do you think I’ll be doing?” I’m grateful in a most definite way.

Thulani Davis is a playwright, journalist, librettist, novelist, poet, and screenwriter.