Driving through Tahrir Square at dusk, crammed into a van with other U.S. and European theatremakers, headed to the conference-sponsored hotel, my eyes couldn’t drink it in fast enough: the lights, the people, the gargantuan propaganda billboards and television screens signaling the impending presidential “elections.” The heat, even in the dark of night, the smog, the crescent moon, the tall glass shop windows selling every item of clothing imaginable under fluorescent lights—“This is Egypt,” I kept reminding myself, awestruck as we pulled into the gates of the Marriott Hotel, a former royal palace.

I arrived in Cairo in late March 2018 to attend the 7th annual Downtown Contemporary Arts Festival (known as D-CAF), specifically for its Arab Arts Focus programming, along with 13 fellow members of the Fence, an informal network of playwrights and cultural operators based in 52 countries. I extended my trip to the seaside city of Alexandria, where I also attended several days of the Theater Is a Must festival, in its fifth edition.

Given the constraints of the military dictatorship under which Egyptian citizens are living, it is a testament to the dedication of artists—both to their craft and their civilian liberties—that theatre is still being produced at all. Playwright Rasha Abdel Monem describes the climate that has developed in recent years as “cold and fearful,” given the censorship barriers and lack of funding. You’re either with the regime, she says, or you’re against it. As an artist, you’re afraid to be labeled as a “threat to the state,” the same umbrella term applied to terrorists. Yet the repression has led to a competitive spirit among those artists still trying to produce work. Monem, for one, feels the “responsibility of writers to record history and reflect culture as it is.” The show, she is convinced, must go on.

At this point, censorship is operating on three levels. A state Censorship Panel, located in the Ministry of Culture, comprises civil servants (not literary people, playwrights are quick to point out). All scripts must be read and approved by the Censorship Panel before being staged, and even the smallest independent theatres won’t consider any script, even for self-production, without the censor’s stamp of approval. Ministry censors are sent to rehearsal and to opening-night performances to guarantee that their changes and redactions have been respected.

In response to the Censorship Panel, some state-run theatres have created literary offices with reading panels of “very bad theatre critics,” according to Cairo playwrights—panels that will reject some scripts before they are even sent to the state panel, citing morality concerns. Finally, given the risks playwrights take by dealing with controversial ideas and themes—particularly those pertaining to the military or government, which are the most likely to be targeted for censorship—many authors are self-censoring their work. Like other civilians, they are susceptible to prosecution in military trials under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s regime.

Of course, crafty theatre people are finding ways to work around the limitations of censorship. Or, as self-taught playwright, director, and journalist Dalia Basiouny puts it, “People have always found ways around stupid rules.” Some resort to bribery, and others use the system of omission, being careful not to use certain words when they know a censor is in the audience. As another model of artists evading restrictions, Basiouny cites the historical example of performers in 18th-century England inviting people over to their houses to have tea at the price of half a quid, while a performance took place, seemingly impromptu, in the background.

Of late, directors in Egypt tend to prefer foreign texts, so that if censors drop in and have an objection, they can claim the action of the play happens elsewhere, not in Egypt. What’s more, censors only have veto power over what is written in the script, leaving room for coded expression in the visual landscape of the play. Sara Shaarawi, an Egyptian-Italian playwright based in Scotland, says, “Given this huge crackdown on the arts, you see the classic Egyptian way of using allegory to relate historic events to now. Physical theatre and movement have always been a huge part of the theatre scene, since you can’t really censor that.”

As Shaarawi and others explain it, there was an explosion of free expression immediately following the revolution in 2011. (English-language critic Joseph Fahim has chronicled developments in Egyptian theatre before and after 2011 in AT, May/June 2014.) Of that post-revolution glow, Basiouny says, “So many people were finding their voices, artistically, theatrically, critically. Many voices were immature and not very well trained, but the energy creating worlds onstage was really fascinating. Not many people continued to do that kind of work, but it was amazing to witness. We were so alive.”

Now, Shaarawi says, everyone in her circles knows what tear gas smells like.

For some time now, theatre has been a way of trying to make sense of it all. “During the revolution, the theatre being made was all about ‘verbatim,’ the truth, the words of the real people there,” Shaarawi explains. “There was an urge to get the stories out as testimony, because of the bias in the media channels. No one was reporting it right, and so theatre was doing the reporting.”

But after June 30, 2013, when President Mohamed Morsi was overthrown in a military coup, “all unity disintegrated and felt superficial,” playwright Monem reports. She believes that writers’ solidarity is the only answer in fighting back against the constraints of censorship: “Theatre, out of all the forms of art, is the one most deeply rooted in community. It’s a celebration. If you don’t write for that community, what are you doing?”

Basiouny echoes Monem’s frustration with the lack of community, saying, “Funding is very limited, so if there are only three chances for something to be produced, the competition is real. There are 20 million people in the greater Cairo area, and the city officially has 16 stages, only 12 of which are in operation.” Further limiting playwrights’ agency, Monem adds, “Playwrights pay companies to give them the sole performance rights to their play for three years, so they can’t stage it anywhere else in that time.”

Basiouny also cites a lack of training for new writers as contributing to this dearth of community. “I believe in theatre,” she avows, “but organizationally and institutionally, there’s something seriously wrong—the way it’s run is not designed for it to improve; it’s designed to feed the status quo and have people profiting from it.”

Given this confluence of obstacles, it’s a struggle to find peers. Basiouny says, “There must be other people who are writing. Where are they? Most of the stuff we see is recycled material or classics.” Shaarawi agrees: “Egypt is stuck with issue plays, melodrama, works about artists expressing themselves rather than thinking about the audience’s place within the world of the piece. Egypt needs better writers—that hasn’t changed.”

Like many other global theatre markets, Egyptian theatre broadly falls into two categories: commercial, state-funded theatre, the more “popular” form; and independent thea-tre, which often takes more risks. Popular theatre tends to be satirical, often with sitcom-style humor. Carnivorous, by Issam Bou Khaled of Lebanon, in collaboration with Sarmad Louis, presented as part of D-CAF, is an example of this type of work. Egypt has a history of one of the biggest theatre industries in the Arab world—“Commercial theatre is still doing it, though it’s deteriorating,” Shaarawi notes—and there is a sense of carrying on that long-valued tradition.

But state-funded opportunities are extremely limited. There are no workshops, and playwrights must present a final version of the script for censors’ approval before the first rehearsal, which leaves no opportunity to make changes during the rehearsal period.

Independent theatres have more limited resources, although they do allow for a workshop process. However, if an organization agrees to accept any financial aid from the state, it is considered a state company—and, Basiouny says, “If you accept a grant from foreign sponsors, some consider you to be a spy.”

“The successful independent arts scene in Egypt is made up of people who have money through other means,” Shaarawi explains. “All the big names graduated from the same American University in Cairo program, one of the most expensive in the region.” Works thought to be more avant-garde tend to use choreographed movement to display their sophistication, since, as artists learn at university, that’s what will set their work apart. Aysha, by Egyptian artist Dalia Kholeif, also presented at D-CAF, demonstrated this trend.

I was surprised to see, in that work and others, that women’s stories, particularly pertaining to mental health, were so prominent in both festivals—so much so that the theme of this year’s Theater Is a Must was “Female Theater Practitioners and Feminine Narratives.” Basiouny and other theatre commentators do not see this trend as positive. “So much of the art that sells in certain parts of the world is catering to the notions of people in other parts of the world about the people being written about—it’s sad that women artists are responsible for creating that,” she reasons. “Women should not be reduced to one tone. And if this is the one tone, can we choose a different tone? If it’s only me, me, me, me—it’s a shame that this is the same trope that young theatremakers are falling into, and that curators are calling for that tone.”

Shaarawi agrees. “A lot of women are at the helm of making things happen and making shows—more women study the arts, fine arts and theatre, and for a long time it was seen as a women’s domain, although a temporary one, because eventually they would get married.” Now, what these playwrights see as stylized, pitiful self-expression is quite in vogue, and is even expected of artists trained with a Western education in Cairo.

Of course, the lack of mobility for Egyptian theatremakers, and Middle Eastern/North African (MENA) artists in general, limits their access to what is happening in global contemporary theatre, thereby making their practice quite insular unless they have the means to go abroad—and, in the bargain, it deprives international audiences of their perspectives. Monem adds that in Egypt there is no market for published plays, and translation of plays both in and out of Arabic tends to be of low quality, which further limits the international exchange of new work.

“The image of ‘the Arab’ is highly stigmatized and highly mediatized, and Egyptians want to fight that image of terrorist, victim, and refugee,” Monem asserts. “We do have stories, and we don’t need white Hollywood people to represent us. In our own little way, it’s a means of fighting the government, the lived oppression—finding ways to get the plays on, that’s a little victory, a little giving-the-finger. We can still do it, say what we want, be free a bit.”

In that sense, contemporary Egyptian theatre serves as a reminder of the power of art as an act of resistance. Just cleaning up a space and presenting a show is in itself revolutionary. “I am a rebel,” Basiouny says flatly. “Revolution transformed me.”

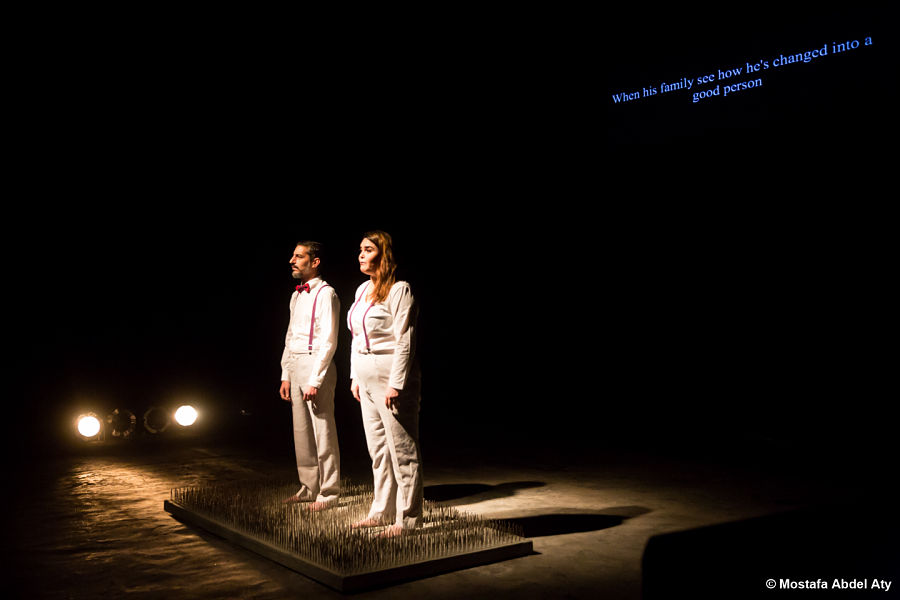

Some works included in D-CAF, such as And Here I Am, written by Hassan Abdulrazza and performed by Ahmed Tobasi, were explicit in their weaponizing of art. Tobasi, on whose life the show is based, grew up in the Jenin Refugee Camp in Palestine and trained there under Juliano Mer Khamis of Palestine’s activist Freedom Theatre. Another D-CAF show, Before the Revolution by Ahmed El Attar, provided an avant-garde take on that radical spirit, with two performers standing barefoot in the middle of a bed of nails, voicing snippets of text and song from Egyptian culture before the Arab Spring, creating a unique sonic landscape from recent history. (Since I don’t speak Arabic and have never lived in Egypt, much of the specificity of this piece was lost on me.)

Nevertheless, when artists are perceived as threats to the state, their voices and their art become their armor, if not their weapons. Adel Abdel Wahab, founder and organizer of the Theater Is a Must festival, says, “I don’t have anything to lose [in producing shows].” This mentality, left over from the revolution, is a striking example of the courage and resilience programmers and artists bring to their work, championing what they know to be important. Basiouny agrees, “Anybody who’s still doing it is defying the odds. There’s a beautiful Egyptian proverb that says, ‘The wise woman can weave with the leg of a donkey.’ If you’re a smart, nifty woman, you can make do. I weave as much as I possibly can.”

Amelia Parenteau is a roving writer, theatremaker, and translator. Recent publications include HowlRound and Contemporary Theatre Review.