In Jan. 23, 1955, the Milwaukee Journal reported, “Mrs. Richard John stood near the entrance of the Fred Miller Theatre welcoming the first nighters and receiving congratulations. She wore a low-waisted formal gown with a silver lamé bodice and a full white tulle skirt. Her stole was of tulle and lamé.”

The article goes on to describe the dresses of all the society women in attendance. But Mary John, as she would be identified today, was no mere society lady: She was in many ways the driving force behind the whole affair, as she had worked tirelessly for the previous two years to bring the Fred Miller Theatre, later to become Milwaukee Repertory Theater, to life.

John was part of the nascent regional theatre movement, which was led in large part by women: Margo Jones opened Theatre ’47 in Dallas in 1947, Nina Vance opened Houston’s Alley Theatre that same year. And in Washington, D.C., Zelda Fichandler co-founded Arena Stage in 1950. Pat Brown, who would later become the Alley’s second artistic director and a founder of Theatre Communications Group, started the now defunct Magnolia Theatre in Long Beach, Calif., in 1954. For the next 15 years many women like them would work to bring to life a new vision of regional theatre in a country that still mostly looked to New York City, and touring productions originating there, as the sole source of artistic quality and innovation. These visionaries wanted a theatre that was more alive, based in community, and not dependent on commercial success. When she was working to build her theatre, Mary John read Margo Jones’s book Theatre in the Round, and “followed her instructions word for word.”

Now 92, keenly intelligent, observant, and witty, John possesses an adventurous spirit and tells her story with generosity and warmth. Born Mary Widrig in Green Bay, Wisc., in 1925, Mary spent the summers of her youth at Chautauqua, a summer arts colony in upstate New York where her father’s family once owned a hotel directly across from the amphitheatre. Her passion for the arts was nurtured by her mother, who was a singer, and by her summers at Chautauqua.

She was always surrounded by music. In high school she participated in the renowned Cherubs program at Northwestern University and attended college there from 1943 to 1947. Ten days after she graduated with a degree in theatre, Mary married Richard John. He had been in the military, serving in Europe during and after World War II, after which he returned to the University of Wisconsin at Madison to earn his undergraduate degree. Mary went with him. There she earned a master’s in directing and wrote her thesis on arena staging. She describes this chapter of her life almost as an afterthought—she was there, so why not? After they both graduated Mary wanted to go to New York, and Richard agreed.

By that time the couple had an infant son. But twice a week she would hire a babysitter and make cold calls to producers’ offices in the hope of finding a way in. She finagled her way into the offices of Paula Stone and Michael Sloane, where the head secretary liked her and hired her as a receptionist. Duties involved taking dictation using shorthand, answering phones, and typing correspondence. Mary bought a book called Alphabet Shorthand to teach herself stenography. She had never seen a switchboard before and her typing skills were lacking in the area of, well, skills.

One day Bretaigne Windust, a prominent director known as Windy, came into the office. He had been hired to direct Carnival in Flanders and was looking for an assistant director. John jumped on the opportunity, with the blessings of her boss. John’s complete lack of qualifications to be a receptionist quite possibly helped her land a dream job. During the rehearsal process, Windy became ill and Mary took over many of the director’s duties. The show had a two-month run in California before he was replaced by the author of the play, Preston Sturges. The play ran for six performances on Broadway, starring Dolores Gray and John Raitt. Dolores won the Tony for best actress that year (and continues to hold the honor for shortest-lived Tony award-nominated performance in Broadway history). So began Mary’s career in the American theatre.

In 1952 Richard John left his job in New York to return to Milwaukee. Mary was still working on Carnival in Flanders at the time, and she stayed behind to finish, then moved back to Milwaukee herself. This presented her with a personal crossroads. As she put it to me, “I knew if I wanted to be happy and have a marriage that I needed to work in professional theatre.” But as there were no options for that in Milwaukee at the time, Mary decided to make something that would not only satisfy her need for theatrical acitivity but would create something for the city she considered home.

At this time McCarthyism had just reached its peak. Milwaukee was politically and socially conservative, known for “the 3 b’s”: baseball, brewing, and bowling. Indeed early press and publicity photos for the theatre show everyone dressed to the nines and drinking glasses of beer, making it look elegant. Into this town of baseball and beer-loving German immigrants, Mary John would bring forth a civic institution and model of regional theatre.

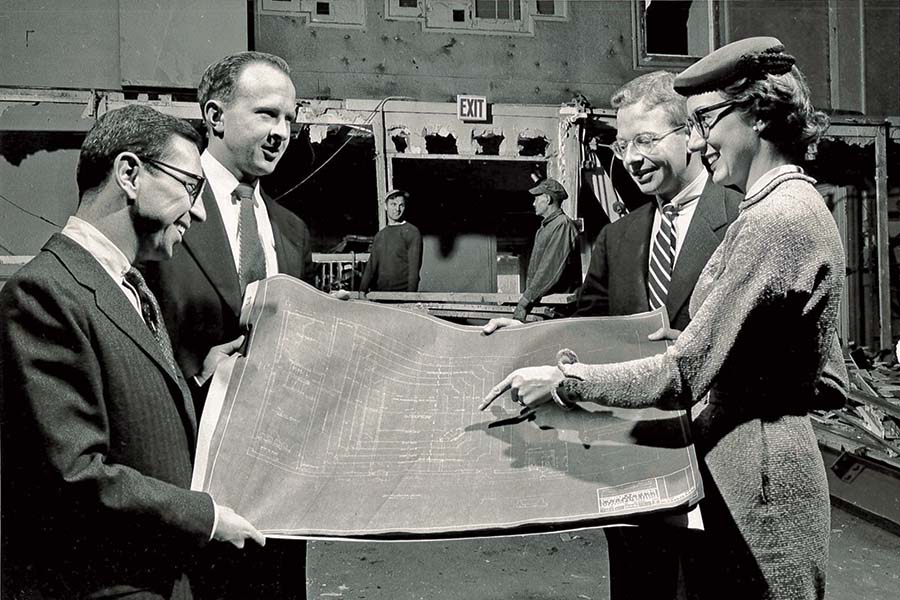

John insisted that everything about the theatre was up to the highest professional standards. She engaged board members from the community. The theatre and an associated school were established as a nonprofit stockholding corporation named Drama, Inc. Because she was really passionate about the civic importance of the theatre, John was determined to have a school associated with it. So she founded a professional school and engaged many involved with the theatre, including visiting artists in teaching there.

John was the major stockholder of the new corporation, holding 51 percent of the stock with the seven board members dividing the rest. She hired Clair Richardson, a public relations and fundraising professional, as the first paid staff person. Richardson would go on to found the Skylight Music Theatre. Together with the community they raised $115,000 to start the theatre (the equivalent of nearly $1.5 million in today’s dollars).

Jane Bradley Uihlein was one of the first to join the cause. A major civic force, she convinced Frederick C. Miller, chairman of the Miller Brewing Company, to chair the fundraising campaign. Miller was responsible for two of the three Milwaukee B’s: beer, of course, but also professional baseball, which he was responsible for bringing to town. He took his civic responsibilities seriously, and John remembers him fondly as one of the few men who took meetings with her and did not make or receive phone calls or otherwise distract himself during their colloquys.

Then, on a day when Miller had gone out of his way to arrange for John to meet a Schlitz executive, she got in her car and turned on the radio to hear the devastating news that Miller’s plane, headed for a fishing trip, had crashed on takeoff and that Miller’s son had been killed instantly; Fred Miller died the next day from injuries he suffered in the crash. Many people donated in his memory, and the theatre was named for him. The project was referred to in the press as “Miller’s last community task.”

The Fred Miller Theatre was known as a “star system” theatre. They produced 10 plays a year, each with a two-week run, and as a ploy to attract audiences, they would allow well known actors to choose their own vehicles: Uta Hagen in Cyprienne, Geraldine Brooks in The Philadelphia Story, Geraldine Page in Summer and Smoke, Florence Reed in Night Must Fall, Eva Le Galliene in her own translation of Ibsen’s Ghosts. Notably, though she disclaims any direct influence, John’s leadership did seem to make a difference on which plays got produced there: In 1954 the theatre produced two plays by women, in 1955-56 six out of 10 plays were written by women, and in 1956-57 four female playwrights were featured. But after she left the theatre the following season, replaced by a male artistic leader, another play by a woman was not produced there until 1961. And no plays by women were produced again until a production of Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes in 1973.

The theatre was a success from the start—or, as Variety put it on March 9, 1955, “Milwaukee Stock Co Away to Boffo Start.” The theatre had grossed $25,900 on a potential of $28,200. In the second season, to accommodate more patrons each production played for three weeks instead of two. According to all press accounts, Milwaukee was very proud of its new addition. John was lauded for her work, referred to as “a Milwaukee girl” who “had it all.” One article from the period describes a day in her life as a glamorous homemaker with a day job. Another describes her as “a woman of great patience, perseverance, and astonishing capacity for tough work,” which, according to John, was more like it. “I worked so hard I didn’t have time to do anything,” she recalled to me. “I had a screened porch where I collected papers I didn’t have time to read.”

Many prominent citizens wrote John notes of appreciation and admiration. On April 10, 1955, she was awarded the Outstanding Service Award by Theta Sigma Phi Sorority “for bringing Milwaukee its first winter stock company since the old German theatres.” In 1958 John was awarded the Modern Spirit Award by the Milwaukee Newspaper Guild, the first woman to be so honored.

But the high times came to an abrupt end. Later in 1958, the theatre was forced to shut down, and by 1960 John was back at work in New York. The huge initital success of the theatre had led some board members and community leaders to think a summer season of plays in a new venue would be successful as well. John disagreed; she was skeptical that Milwaukee audiences could support two theatres. A summer season, she felt, would hurt the success of the Fred Miller Theater. She also thought that the staff needed a break from the grueling 30-week season of 10 plays. So she refused to take part in the formation of a new theatre. Her intuition proved accurate: The new summer theatre, the Melody Top Tent, which shared top board officers with Drama Inc., was a disaster, plagued by tent collapses, low ticket sales, and various other problems. It closed after one season (though some years later it was revived).

As no minutes from board meetings from the time are available, it is difficult to know exactly what happened. According to John, one of the leaders in the summer theatre who in fact was the same board member who drew up the articles of incorporation for Drama, Inc., brought suit against the company, charging that it had been illegally incorporated. He implicated himself as “making a mistake.” Indeed a law had recently been passed making nonprofit stockholding corporations illegal, though it has been legal when Drama, Inc., incorporated. Some correspondence indicates that certain board members may have been coerced into joining a campaign with the goal of convincing the Wisconsin Attorney General to force a reorganization of the theatre on a non-stock basis. The board members sent postcards to ticket-buyers, supporters, and citizens enlisting support for such a move. Many returned the postcards agreeing with the plan, including the lawyers who drew up the original papers of incorporation.

And none of the original board members wanted to be involved with the Fred Miller Theatre any longer, apart from except Doris Hersh Chortek. Dori, as she was called, had helped to start the theatre and stuck with John through thick and thin. They remained friends until Chortek’s death in 2014.

A judge reorganized the theatre as a non-stockholding corporation with a board of 30 directors, and ordered John to surrender her stock. He also offered her the first seat on the board, which she refused. Less than three years after opening the theatre and enjoying tremendous success and a reputation as a civic leader and entrepreneur, John was forced out of the theatre she founded. She left the theatre with $115,000 in the bank. She had promised the community that they would not have to raise any more money, and it is a strong point of pride for her that she kept her word on that.

After she left the new board hired a new director who lasted for just one season; the company struggled through the next few years. For a time the “star system” was kept in place, but in 1961 the company became a resident theatre company, and while it took many years and scores of dedicated staff and board members, it eventually became the extraordinary resident theatre we know today. In the first program Mary had written, “Whenever applause is sounded in this theatre, it is a tribute to these far-sighted citizens.” She was referring to those who helped found the theatre with her, but her words could be applied to all those who continued and continue to do the work she began.

The Johns’ marriage also fell apart around the time she left the theatre she founded and moved back to New York. John says it had nothing to do with the dissolution of the theatre but more to do with marrying too young and growing apart. She now admits that she may not have been happy running a theatre much longer than she did, as her interest and talents lay in the creation of something new that would be of value to the community. She went on to earn a Ph.D. from New York University and produce a number of plays in New York, including Colette with Zoe Caldwell at the Ellen Stewart Theatre and Dear Oscar on Broadway. She fondly recalls producing shows in Monaco at the invitation of Princess Grace. She ran the Ballard School in New York, a continuing education school. While there she worked in a government program that trained secretaries to become managers.

She also directed a musical theatre studio affiliated with Northwood Institute of Dallas for 17 years. She was passionate about teaching actors about the business side of the theatre; in that program tudents studied and rehearsed for part of the day while learning about the business side for the other part. Many graduates of this program are still performing on Broadway and across the country, including Victoria Clark, Kevin Ligon, and Rebecca Eichenberg. She met her second husband at the age of 70 and married him at 77.

John does not think of herself as a groundbreaking. And though she was presented as a debutante and “put in her time at the Junior League,” she does not think of herself as a society lady either, no matter what the Milwaukee Journal records. Instead she thinks of herself as a professional theatremaker. Indeed her trailblazing work was essential to what we know today as regional theatre: her impulse to create something of civic value, her insistence on excellence, and her determination continue to serve the American theatre in ways she could not possibly have foreseen.

Deb Clapp is the executive director of the League of Chicago Theatres and has a particular interest in researching and writing about the important stories of women founders in our industry.