If you ever want to meet some really patriotic Americans, you should go into immigrant communities. More specifically, you should meet my father. He loves Budweiser (and sincerely believes it’s the “king of beers”). He has a fast food preference (Burger King over McDonald’s). He puts out an American flag every July 4th.

As a Vietnam War vet and an immigrant, my father believes in the promise of America. “You are living in the greatest country on Earth,” he would tell me growing up. “You can become anything.” On our first trip to Washington, D.C., when I was 10 years old, among the souvenirs my parents bought home was a mug with photos of every American president. It survived through my high school and college years. After 2008, they took another trip to D.C. and bought a new mug with Barack Obama’s photo on it. I was raised assuming that of course the Constitution protected me—that as a permanent resident and then, in 2000, as a citizen, I was entitled to the same rights and protections as anyone else in the U.S.

I was thinking about patriotism when I sat down for Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me at New York Theatre Workshop last week. It was the day after the Brett Kavanaugh Senate hearing, and Christine Blasey Ford’s voice was ringing in my ears. I thought of the faces of the white male Senators in that hearing, unmoved by her words. What does patriotism mean when your country, your government, is giving you so little to feel patriotic about?

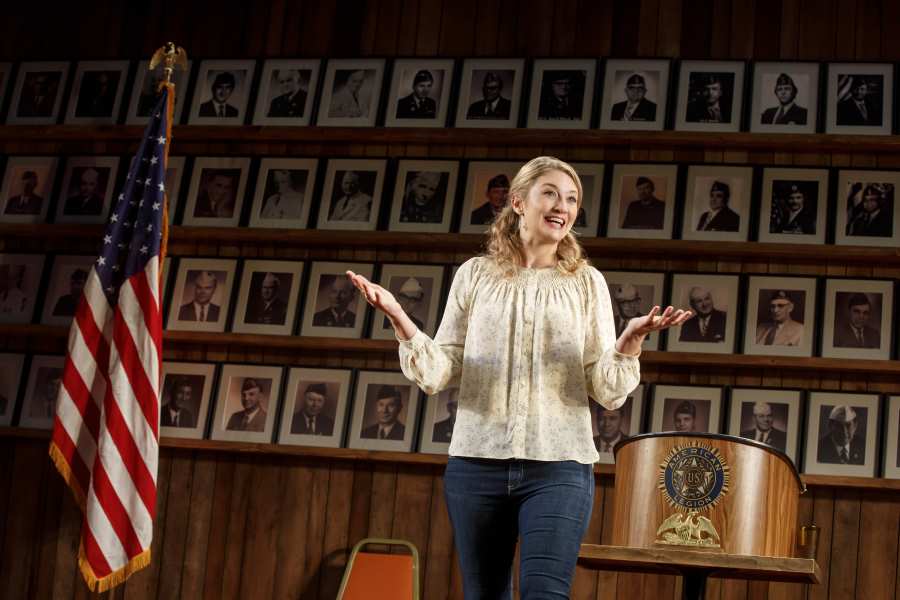

What the Constitution Means to Me is partly playwright/performer Schreck’s revisiting her 15-year-old self, when she gave speeches around the country at American Legion halls about the Constitution, and took home prize money that paid for her entire college education. But in addition to giving us some of the exact speech she gave at 15, Schreck also gives us a dissection of the Constitution as she understands it now, as a fortysomething-year-old woman. (Schreck’s plays include Grand Concourse and she has written for the TV shows “Nurse Jackie,” “I Love Dick,” and “Billions.”)

What she discovered in the 10 years she spent working on the show, and in reflecting on her own life and those of the women in her family, a number of whom were abused, is that for all the progress the Constitution has made possible—the 14th amendment’s equal protection clause, for instance, which has enabled the Civil Rights movement, the legalization of same-sex marriage, and workplace rights for women—the document has overall fallen short in protecting women from violence. Women and marginalized bodies are left out of the Constitution, and that “equal protection” has only been won in some cases by acts of judicial interpretation. And currently, the question of who can become a citizen is being debated, with denaturalization a very real threat.

Which brings us back to Dr. Ford, who has gone into hiding because of death threats after her brave testimony, and who was ridiculed earlier this week by the president at a rally where the crowd chanted, “Lock her up.”

“When I started making this 10 years ago, I had fundamental faith in this document,” Schreck tells the audience. “I knew that the people who made it were slave owners who didn’t think women and people of color were fully human. But I believed in the genius of this document, in its ability to evolve over time. Now I wonder, though, what does it mean that the document will not protect us from the violence of men?”

Indeed. And what does it mean when the most powerful man in the world is an alleged sexual predator? And that soon there will likely be two Supreme Court justices who are alleged sexual predators? What does it mean to live in a country that tells you your pain is meaningless in the face of male ambition?

I guess this is a question those of us on the margins have been asking for centuries. We continue to ask it now: What does it mean to be a citizen in the face of such soul-crushing antipathy?

Several people have compared What the Constitution Means to Me to Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette, particularly the way it takes the one-person, autobiographical show and morphs it to make a wider commentary on our general culture of misogyny.

https://twitter.com/HalleyFeiffer/status/1046234443571232768

Sure, you can compare it to Nanette. But you can also compare it to another piece of storytelling. Last week two women confronted Arizona Senator Jeff Flake in an elevator after he announced that he would support Kavanaugh’s nomination. Maria Gallagher and Ana Maria Archila each told him their own stories of assault in a video that went viral.

“Don’t look away from me,” said Gallagher to Flake. “Look at me and tell me that it doesn’t matter what happened to me, that you will let people like that go into the highest court of the land and tell everyone what they can do to their bodies.” Though it’s not clear if it was a direct result of this confrontation, Flake later requested that the Kavanaugh nomination be put on hold so the FBI could investigate Ford’s claims.

In an interview with Pod Save America, Archila explained why she had spoken up, saying that women like her and Ford are “forcing the country to include women in the promise of freedom. By not ignoring the violence that is imposed on us, the intimate violence and the sexual violence. By not continuing to perpetuate the political violence that diminishes our voices.”

What women like Ford, Archila, and Gallagher are doing now is what historically women and marginalized people have always done: Look at these documents of law and demand that those in power write us in.

Of course, having the power to change the law requires lawyers, organizers, and politicians. But What the Constitution Means to Me reminded me that it also requires regular people having the courage to tell their stories. Ford described telling her own story as her “civic duty…It is not my responsibility to determine whether Mr. Kavanaugh deserves to sit on the Supreme Court,” Ford told the Senate judiciary committee. “My responsibility is to tell you the truth.”

In the last 11 months, as numerous people have reached out to me with their own stories of sexual harassment and abuse, I have been reflecting on the importance of storytelling, and why artists tell stories. Schreck told Slate that her goal with the play every night is “to get through it and speak the stories out loud, because I think there’s great power in that.”

The #MeToo movement didn’t just expose the sexual predators among us and force society to have a wider conversation power abuse and consent. It also showed the reason why those stories have been historically stifled by threats of violence, non-disclosure agreements, and payoffs—indeed how the legal system has been used to constrain rather than liberate women.

It was women’s stories and their courage in telling them that took down Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, and they are what have called Kavanaugh’s character into question. A woman telling her story and demanding to be heard is a powerful and political act.

The most patriotic thing a person can do is tell her story.

My favorite two words in the Constitution are “more perfect,” as in, “We the people, in order to form a more perfect union.” The country has never been perfect or even “great,” and making it “more perfect” would be part of the ongoing struggle of America. As someone who comes from Vietnam, a country where free speech and dissent means imprisonment, my dad always told me that the ability to speak is one of the most valuable rights we have as Americans.

Since Trump was elected, many artists have been wondering aloud on social media and to me in private conversations: What is the role of art? After all, live performance is severely underfunded in America and is seen by many regular Americans as frivolous or elitist.

Does great art affirm, challenge, or provide answers? Maybe, as in the case of What the Constitution Means to Me, it’s all of the above. The play begins as an affirmation of the Constitution’s reputation as the oldest active constitution in the world, then turns into a challenge of what the document represents, then turns it back on us to make up our own minds. It ends with a parliamentary-style debate between Schreck and a girl of color (two local teens rotate the role every night) about whether we should abolish the Constitution and write something better. The audience is the judge.

The night I went, Schreck was arguing for abolishment, and 17-year-old Thursday Williams (who goes to school in Queens) argued for maintaining but improving it. If I came in wanting to burn everything to the ground, it was Williams who pulled me back from the brink.

“Why not just think of the Constitution as a human being?” she said, explaining that the document was, after all, made by human beings. “Just like us, this document is flawed. But just like us it is also capable of getting better and better. With every generation.”

Then she paraphrases Abraham Lincoln: “The people should not overthrow the Constitution, but to overthrow the men who abuse it.” On the night I attended that line received cheers from the house, and from me. And the most radical thing was: I didn’t know which side I supported. I couldn’t follow with blind gut, I had to think for myself. Schreck and Williams was redefining what political theatre could be, something that was not polemic or didactic, but personal and urgent. America was founded on dissent and debate, and through dissent it has been made “more perfect.”

In a week where the overriding emotion for myself and many women was the fury of a thousand Medeas, What the Constitution Means to Me underlined the value of staying engaged, of continuing to tell our stories, even when the outside world is telling us to be silent. It was something I heard repeated over and over again this past year, as more women came forward with their #MeToo accounts: “I tell my story so other women won’t go through what I’ve gone through.”

This is what previous generations of feminists did for us in demanding the right to vote, for equal rights, for the right to birth control and abortion. So that girls like Thursday Williams and my own nieces, 6 and 9 years old, can look at the Constitution and see themselves not in the margins, but in bold text.

President Obama has described progress as a pendulum that swings in one direction before swinging back from where it came. In What the Constitution Means to Me, Schreck describes progress as a woman walking on the beach with a dog. “If you watch the dog it keeps running ahead and then running backwards, so that if you only keep your eye on the dog it seems like progress is constantly being undone,” she says. “But if you watch the woman, you can see that she is moving steadily forward and forward and forward.”

Women have pulled, and will continue to pull, this country forward, and we’re going to lead with our stories.

What the Constitution Means to Me is currently running at New York Theatre Workshop through Oct. 28.* It will next travel to Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company in Washington, D.C., April 1-28. The play is directed by Oliver Butler and features scenic design by Rachel Hauck, costume design by Michael Krass, lighting design by Jen Schriever, sound design by Sinan Zafar, dramaturgy by Sarah Lunnie, and stage management by Terri K. Kohler.

*Edited to add: What the Constitution Means to Me will now play Nov 27–Dec 30 at the Greenwich House Theater. Considering that Gloria Steinem; Hillary, Bill, and Chelsea Clinton, have all seen it, we consider this extension a great move.