Playwright Neil Simon, who wrote more than 30 plays and nearly the same number of movie screenplays, and received more combined Oscar and Tony nominations than any other writer, died on Aug. 26 at the age of 91. At a memorial service on Aug. 30, speakers included the actors Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick and Simon's longtime publicist, Bill Evans, who donated a kidney to Simon in 2004. Below are edited versions of their remarks.

Nathan Lane, actor

Neil Simon was a giant of the 20th century American theatre, a meticulous craftsman who fashioned his own style of comedy, building on the work of his idols, George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, creating indelible characters with whom we can all identify, laughing with them one minute and crying for them the next. It is a formidable and unparalleled body of work that started with his teacher and older brother Danny, writing for radio and then joining the most famous writers’ room in television history for “Your Show of Shows,” starring the incomparable Sid Caesar. Then finally breaking into the theatre with his first play, Come Blow Your Horn, followed by a remarkable string of hits that defined the Broadway comedy for 30 years, culminating in his great autobiographical trilogy and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Lost in Yonkers. An extraordinary track record rivaled only by Shakespeare. Of course, Shakespeare didn’t have the advantage of working with Mike Nichols on his early plays. But it all sprang from the mind of one shy boy from the Bronx, Marvin Neil Simon.

I first encountered Neil Simon when, at the age of 11, I joined a play-of-the-month-club called the Fireside Theater. One of the first plays I ordered was a new comedy from the celebrated author of Barefoot in the Park called The Odd Couple. I was so excited when it arrived I could hardly contain myself; it felt like Christmas morning and my birthday all at once. It was a beautiful hard cover copy with many black-and-white Martha Swope photographs of the production and its two stars, Art Carney and Walter Matthau.

Many years later at a dinner with Matthau he told me, “If it wasn’t for Neil Simon and The Odd Couple I’d be an obscure character actor in regional theatre right now.” I assured him he was wrong, but he knew he would always be indebted to Neil and his work, and I felt the same way.

Anyway, when I was 11 I couldn’t wait to start reading this “hurricane of hilarity,” as it had been called, and wound up taking it to school with me. It was a strict Catholic school run by an elite task force of deadly Dominican nuns. During a world geography class, I had hidden my precious copy of the play inside my textbook and started reading it. At some point the hurricane hit and I burst out laughing, and the nun in charge, Sister Vin Diesel, angrily inquired, “What’s so funny, Mr. Lane?” Out of desperation I said, “The International Dateline is imaginary? Hilarious.” And she beat me senseless. But Neil was already influencing my sense of humor.

When it comes to Neil Simon, I admit I am not objective. I am an unabashed fan. He was and will always remain one of my theatrical heroes. Far too many years ago, I almost went to college and found myself at an admissions interview for the NYU School of the Arts. At a certain point, the interviewer asked me to name my three favorite playwrights. I said, “Eugene O’Neill, Samuel Beckett, and Neil Simon.” The interviewer looked slightly aghast and I said, “He writes about people in pain too. It just comes out differently.” I didn’t get in, but I didn’t want to go to college anyway. I wanted to work in the theatre. And eventually I was lucky enough to work with Neil Simon.

In 1987 I auditioned for the national tour of Broadway Bound, and later that day was offered the role of the older brother, Stanley. Neil was there, but I didn’t get to meet him. In fact, that didn’t happen until several months later at opening night in Los Angeles, at the Ahmanson Theatre. After the show there was a knock at the door and I opened it and there he was: taller than I imagined, with the famous horn-rimmed glasses and that mysterious Mona Lisa smile that seemed to say, “I know something you don’t know, and I’m probably going to write a play about it.” I was terrified to meet one of my heroes in the flesh, and I think he sensed that and immediately put me at ease. He was very kind and complimentary, and when he left I was walking on air. I felt I had pleased the master and it felt great.

To be honest, that was really the basis of our relationship. I never wanted to let him down or disappoint him. And when I did well by him it was incredibly gratifying. Several years later, Jerry Zaks asked me to do a new play by Neil about his time writing for Sid Caesar, called Laughter on the 23rd Floor. I was originally asked to play one of the comedy writers, but eventually wound up playing the Sid Caesar character, Max Prince. Neil said what I lacked in height, I made up for in anger. But I would have played any part just to get to originate a role in a new Neil Simon play. Plus I had the joy of going out of town and getting to see him in action. One day during a rehearsal, I saw him scribbling on a yellow legal pad in the theatre and I got up the nerve to say, “What are you writing?” He said, “A speech for you, actually. We’ll put it in a few days from now when you’ve had time to learn it.” He showed it to me and it was really funny, so I said, “Why wait? Let’s put it in tonight!” He loved my enthusiasm, and from then on he felt comfortable giving me new lines, even at the last minute, and I was thrilled at the chance to try them out for him. It felt a little like being in the actual writers’ room, with Neil whispering lines to me instead of Carl Reiner, as he used to do back then because he was so shy, and then Carl would call out to everyone, “Neil’s got it!”

One day he was giving me some notes on a scene in my dressing room and I noticed Neil kept looking over at this large humidifier sitting on my dressing table as we chatted. It was a big blue water-filled tank from which steam would slowly and steadily rise. He couldn’t stop looking at it. Finally we finished talking, he went to the door, and with perfect timing he turned back, pointed to the tank, and said solemnly, “By the way, Nathan, I think your fish is dead.” And I thought to myself, Neil’s still got it!

In 1995, I had the pleasure of performing a tribute to Neil when he received his Kennedy Center Honor. It was a sequence in which Christine Baranski and I would read monologues from Neil’s plays, and then the legendary Sid Caesar would speak in his famous double-talk foreign gibberish. You had to be there, but Sid was nothing short of brilliant and brought down the house. And I got a few laughs myself reading Oscar Madison’s tirade about all of Felix’s annoying habits. About eight years later, Neil wrote me a beautiful note saying he was remembering my performance of that speech and wanted to see me do the whole thing in a revival of The Odd Couple. Talk about a delayed reaction, but wow.

I almost fainted and my inner 11-year-old self cried. I leaped at the chance, and coming full circle, I used the very same copy of the play in rehearsal that I had hidden in a textbook when I was a kid, and sheepishly asked my hero to sign it. A long way to go for an autograph, but what an honor it was to perform that classic American comedy.

The last time I saw Neil, he and his lovely wife Elaine Joyce had come to see me in a new play on Broadway. He looked a little frail, and didn’t seem fully like himself, but was full of enthusiasm for the play and the performance and what we were trying to achieve. I was extremely touched by this and then we said our goodbyes and I got in the car that would take me home. As I sat in the back of the car I noticed Elaine and Neil trying to hail a cab in the hellish Times Square traffic, so I asked the driver to rescue them and he ushered them to the car and I jumped up front with the driver and we took them home. They were sweetly grateful and Elaine and I chatted all the way to their apartment building, while Neil was a little quiet. So many memories and thoughts flooded my brain. Here I was, this littl e kid from Jersey City giving a lift to Neil Simon, the famous and brilliant writer who had given so much to me and countless others, whose wit and craft and humanity had affected me as a kid, and was one of the reasons I wanted to be in the theatre, and here we were together in this car now, and he still made me feel 11 years old, and it all broke my heart a little. And then there we were at their apartment and the doorman was helping them out, and I said goodbye and Neil said, “Thanks, Nathan. By the way, would you mind coming up and tucking me in?” I laughed heartily and I turned to the driver and said, “You know who that was?” And he said, “Neil Simon? Sure. He made America laugh.”

If, as we’ve often been told in the words of beloved character actor Edmund Gwenn on his deathbed, that “Dying is easy, comedy is hard,” no one knew that better than Neil Simon. Unfortunately, he made it look easy, as most geniuses do, and did it so consistently, so prolifically, and so successfully for over 30 years that, in spite of winning every award known to man, with the possible exception of the Latin Grammy, he was often taken for granted or dismissed. Show business is not for the faint of heart.

But all he ever wanted to do was write plays. Nothing made him happier. Except perhaps hearing an audience roar in recognition of something being said by one of his characters, or the beautiful silence you can only hear in the theatre when you can sense a large group of people turn into a single organism, and they’re thinking and feeling and breathing as one, as Neil would hold up a mirror to show them who they are and who they might become.

In the words of Mike Nichols, “I remember those days the way we are meant to remember our childhoods and rarely can. We were really happy. Neil was a very great comedy writer finding his excitement and where it led him and those of us who did his plays were astonished and excited too. All this comes from Neil. He is never satisfied, always working on how it can be better. I don’t see how he could be better. I loved him then and I love him now. He stands alone in his category, he is the standard, but he will never be alone because of all of us who love him.” Amen.

Bill Evans, publicist

I woke up this morning feeling nervous. My left eye was twitching. My back was aching. Then it hit me, “This is perfect Neil Simon!” Every time I called Neil over 42 years, all I had to say was, “How are you?” Then I had three to five minutes free and clear to straighten up my desk and balance my checkbook while he expounded on his ailment of the day.

“I’ve got arthritis in my big toe!”

“All my teeth are out of alignment!”

“My creatine level is lousy!”

Then we’d get to the business at hand. Neil and I clicked from the beginning. Manny Azenberg took a chance and hired me in 1976 on California Suite. I was 26 years old. I had never handled a show as a senior press agent. Manny and Neil called me their token WASP. At one point they made me an honorary Jew—this was many years before Neil had my Presbyterian kidney.

Neil and I became friends. Neither one of us has an easy time of letting our emotions come up to the surface. So much was just understood. He saw me through some very rough times, and I learned how to be there for him. My goal was always to be Best Supporting Actor in the movie of Neil Simon’s life—a comedy, a drama, but never a tragedy.

One time when he was depressed, I showed up unannounced at his apartment in the Ritz Tower. He opened the door and said, “What? Did you think I was going to kill myself?”

“Yes,” I replied. “Let me in!”

Of course I was witness to one of Broadway’s longest-running productions, The Neil and Manny Show. Their partnership began with The Sunshine Boys in 1972. Manny masterfully rolled out Neil’s plays on Broadway through the next 30-plus years. Eventually Neil and Manny became the Sunshine Boys themselves. I played the Richard Benjamin part.

I’ve been thinking of all the extraordinary people who assembled around Neil’s plays and films—Mike Nichols, Bob Fosse, Gene Saks, Bob Moore, Cy Coleman, Marvin Hamlisch, and Michael Bennett, all brilliant collaborators who sparked Neil’s imagination during the realization of each project.

The list of actors who distinguished themselves playing roles written by Neil Simon is very long. There are a few who must be named: Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, Carol Burnett, Phil Silvers, Walter Matthau, Jack Lemmon, Lee Grant, Robert Redford, Maureen Stapleton, Peter Falk, Marsha Mason, Linda Lavin, Mercedes Ruehl, Nathan Lane, Christine Baranski, George C. Scott, Katie Finneran, Penny Fuller, Anita Gillette, Lewis J. Stadlen, and Elizabeth Ashley. I apologize to those I’m leaving out.

In 1979, Lucie Arnaz was starring at the Imperial in They’re Playing Our Song, while Larry Luckinbill was in Chapter Two at the Eugene O’Neill. They fell in love over between-show dinners at Joe Allen, got married, and named their first child Simon. That’s the kind of genuine devotion Neil inspires.

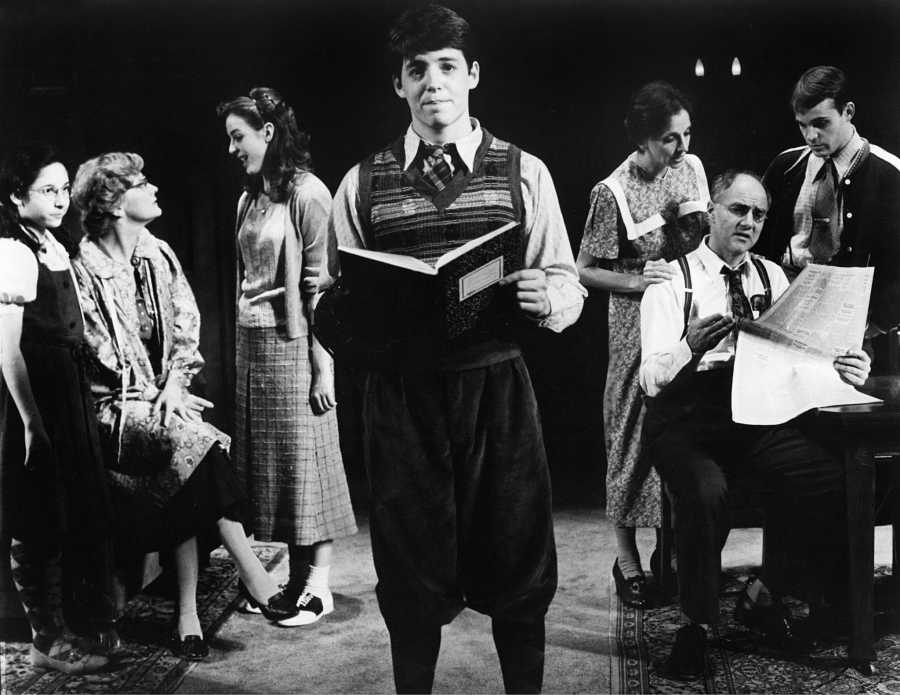

In the universe of Neil Simon, it’s not possible to overstate the significance of Matthew Broderick. He brilliantly introduced Eugene Morris Jerome to the world, enabling us to understand Marvin Neil Simon more intimately than before. Matthew’s Broadway debut performance gave wings to Brighton Beach Memoirs, inspiring Neil to write Biloxi Blues and Broadway Bound.

I have a vivid memory of Matthew onstage in his baseball cap and knickers, addressing the audience, taking us inside the mind of Eugene, whose ambition was to play for the Yankees, or, as a second choice, become a writer. We embraced Eugene, and by extension Neil Simon. That affection lasted a lifetime.

As an opening night gift for Laughter on the 23rd Floor, Neil gave me a framed window card, with the inscription, “To Bill Evans, my consigliere.” I bid the fondest farewell possible to the Godfather.

Matthew Broderick, actor

The first movie I ever did was written by Neil Simon.

I had been reading for a final callback for his play Brighton Beach Memoirs,

and at the end they handed me a film script and said, “Read this too.” It was like someone had told me, on my way out, “Here, take a film career too.”

And so I found myself in L.A., rehearsing in a fake house built inside a sound stage at 20th Century Fox. Neil Simon, Herbert Ross, Jason Robards, Marsha Mason, and me—gulp. We were staging a scene in the fake kitchen, and there was a break while we were figuring something out and I looked at Neil. He was standing over

the sink looking in. He reached in, pulled out one of those rubbery suction cup drain covers, showed it to me, and said ,”These are good in salad.”

I first met Neil a year earlier, in 1981, I believe, when it was my incredible luck to have a chance to read for Brighton Beach Memoirs. I had read for the assistant casting director, then the casting director, Marilyn Szatmary, many, many times—the process was quite long, but finally I was going to be reading for Neil Simon and Herbert Ross, in an actual Broadway theatre. Before that audition, they at last let me read the whole script. I went to Mann Azenberg’s office (they wouldn’t send it out). I was put in an empty room and handed this thick, hand-typed script. It said “By Neil Simon” on the cover. I was suspicious of that, because I wasn’t entirely convinced there was an actual person named Neil Simon. I think I thought Neil Simon was more a type of play. Or maybe Neil Simon was a factory somewhere in Newark, with smoke stacks and floors of writers, typing away. No one person could have produced so much beautiful, hilarious material.

Finally (I’m a slow reader), I finished the script and I sat there, holding it. I felt I was holding a beautiful cigar box filled with diamonds and rubies. It was absolutely perfect. Hilarious, moving, and at the center this wonderful part, Eugene Morris Jerome. The best part I’d ever read. 1937, Brooklyn. Not my life, but it felt exactly like my life. How did he know so much about my life? I was pretty pissed off reading it, too, because I knew they would never cast me and I’d have to watch some less talented person than myself get the part, and get all the accolades.

The next day I went to the Belasco Theatre, stood on the set of Ain’t Misbehavin’ and read for Neil. He was, it turned out, a real person. I was onstage, he was in the darkened theatre, but I could see him: a clean, pressed cashmere sweater, a collared shirt, and glasses. He was quiet, but during the reading, I did hear him laugh—at his own material, but also at me. A soft giggle kind of laugh that lasted a long time. That’s a sound I’ll never forget.

I still can’t hardly believe it happened, a dream come true.

But Neil was was quite serious too. I remember I would try something new in rehearsal, a new approach, a new reading, and out of the corner of my eye, bam, I’d see Neil lean over to the great director Gene Saks and whisper, “Is he gonna do that?” Gene didn’t even have to give me the note, I’d take it out.

Another acting note from Neil once: He came to my dressing room before a preview and said, “I don’t mind when you make little mistakes in your monologues or skip little things—I don’t mind that, but I don’t think you should say, out loud, ‘No, that’s not it.'”

We worked together five times. Our relationship of course had ups and downs; we were both pretty strong-willed people and the stakes were always so high. There were arguments and a few things I regret, but a compliment from Neil, often in the form of a beautifully hand-written note, sitting on your dressing room table was absolute heaven.

Speaking of long laughs, there was a moment in Brighton Beach where Kate, Eugene’s mother, says: “Go to the store, get a quarter pound of butter.” Me: “I bought a quarter pound of butter this morning. Why don’t you buy a half pound at a time?” Kate: “And suppose the house burned down this afternoon? Why do I need an extra quarter pound of butter?”

She goes back into the kitchen. Eugene turns to the audience and says: “If my mother taught logic in high school, this would be some weird country.” And the laugh would go on so long, I could get myself all the way from stage left to stage right to exit. Neil said, “I can’t believe that laugh, it gets you all the way across the stage.”

I loved those notes but no more than I love his plays. His plays are a letter to all of us, in a way. Intimate letters of his life, his loves, his dreams, his parents, his children, his brother, his friends. His virginity and loss of it.

I am so honored to have been a part of his life. I feel a deep loss right now, the loss of a voice, of a perfect ear, of an era, a way of life. But those big beautiful hilarious plays and movies are still there for all of us—that’s a writer’s gift. We can cherish them and perform them and remember the man who wrote them.

The man who was much more than a factory in Newark.