Harlem has always been a city of revival and renaissance. And by the end of this fall, Harlem will have seen two productions of Antigone revived for today, mounted by two different theatre companies with new twists that give power to artists of color. What is it about Antigone that speaks so well to this moment?

The story of a young woman who protests the Greek state’s prohibition on mourning her dead brother, to the point of sacrificing her own life, resonates in the age of the #MeToo movement and NFL protests of the national anthem, said Carl Cofield, who directed Antigone at the Classical Theatre of Harlem (CTH) this past July and is now the associate artistic director of the company.

“Antigone was a great choice because it’s a story of a woman who finds the courage of her convictions to speak truth to power,” Cofield said. “And I really thought that would resonate with a Harlem audience. I think unfortunately in our political climate now, we’re seeing a mentality of, ‘Those people don’t deserve compassion,’ ‘Those people are not us,’ and I believe Antigone’s thing is, ‘No, we should honor the dead, and they should be treated with humanity.’ And I think that’s something that’s sorely missing from our discourse now.”

CTH artistic director Ty Jones, who played Creon in Antigone and helped condense and adapt the piece (based on Paul Roche’s adaptation) alongside dramaturg Shawn René Graham, said that the Sophocles classic resonates today because Greek plays examine who we are as humans.

“Greek plays are unafraid to question everything we value—including life,” said Jones. “Antigone is a story where the people, who assert they are right, clash with a system whose leaders have the same assertion. After 2,500 years, Antigone still asks of us: Are we all players on an odyssey to find our shared humanity, or are we in a perpetual state of ideological warfare that will always end in inhumane violence?’”

Bryan Doerries, the artistic director of Theater of War Productions and the translator/director of Antigone in Ferguson, which will play Harlem Stage this fall, agrees, saying that this work has the power to start conversations.

“I use Greek plays not as a given good, but as a tool for social engagement,” Doerries said. “They’re so effective because they’re not documentary in their nature—they make you think, what do you see of yourself in this ancient text? It shortens the distance of time and the distance of the plays.”

While the specific structure and lenses of these two Antigones differ (CTH’s version was a full production with an Afropunk approach, Antigone in Ferguson will be a dramatic reading that incorporates real discussions and a choir), it’s clear that for both what matters the most is the humanity and potential for connection that this classic text brings. More than two millennia after it was written, Antigone speaks to a 21st-century audience’s sensibility, with open dialogue at the forefront.

At the Classical Theatre of Harlem (CTH), where its summer season is known as the “uptown Shakespeare in the Park,” the Afropunk Antigone ran July 7-29 at the Richard Rodgers Amphitheater in the Marcus Garvey Park. Director Cofield aimed to give voice to the black community in the age of #BlackLivesMatter.

“I was led by seeing some of the traumatic things that black people have been facing in the country,” Cofield said, “where people were being shot and killed by the agents of the state, and siblings trying to rush to comfort their shot siblings and were being restrained by the police. I think that’s something that has an equal parallel in Antigone.”

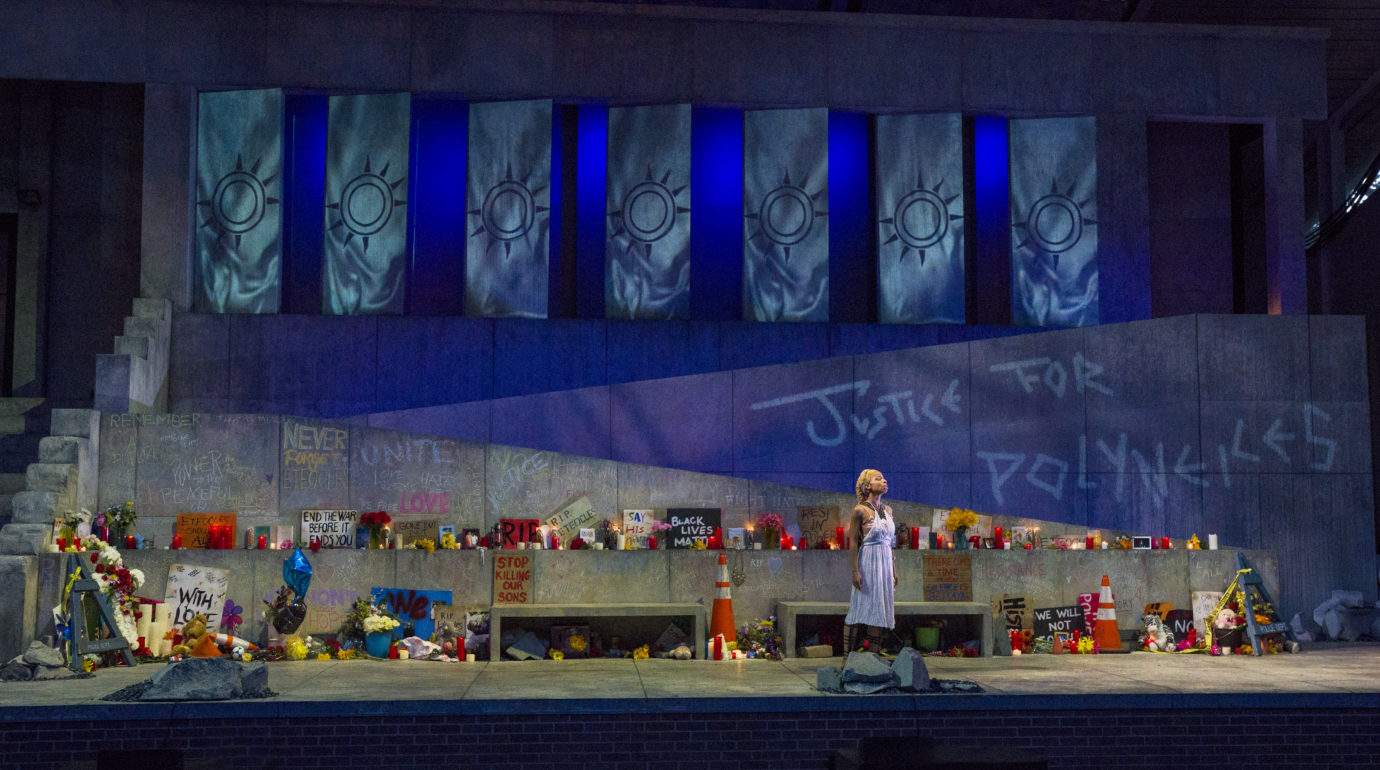

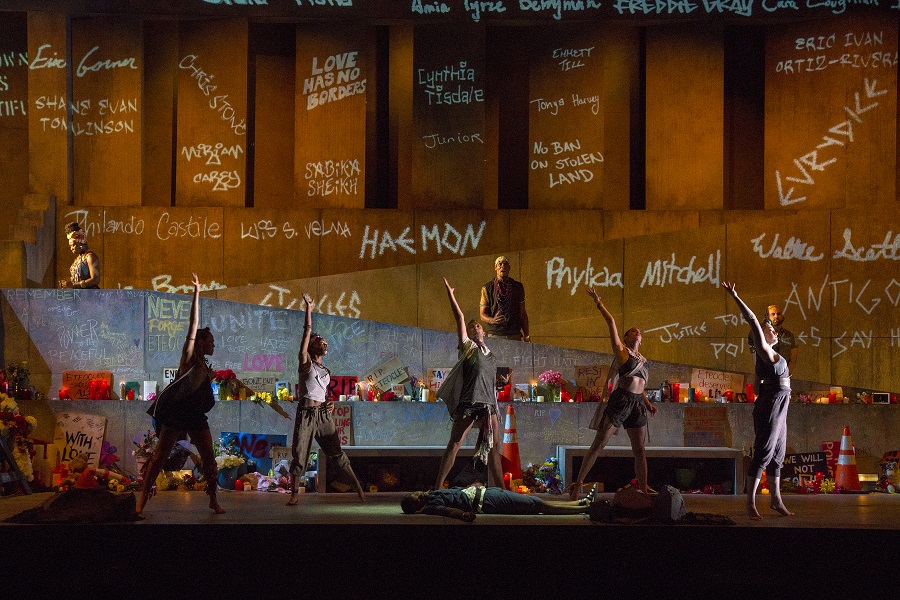

Cofield coordinated with scenic designers Christopher and Justin Swader to realize his vision of a “wailing wall” with candles and memorials as a place where the community could mourn and share their grief for the fallen of the war. Before the show, the wall contained eerie news tickers of headlines conveying a false peace in a dystopian future; by the end, projections of graffitied names, designed by Katherine Freer, filled the wall: Polyneices, Antigone, and many black victims of state or vigilante violence, including Trayvon Martin, Freddie Gray, and Sandra Bland.

”I wanted it to feel like that the majority of our audience, the minute they saw it, without hearing a word, would understand exactly where we are, and it would tell a story nonverbally,” Cofield said.

He was inspired by the Afropunk movement’s cornucopia of beautiful colors and reclaiming of hairstyles and makeup applications. References to Harlem culture (such as a mention of the Whole Foods on 125th St.), contemporary choreography performed by an ensemble that included dancers from Elisa Monte Dance, and soloists singing gospel hymns as a way to “mitigate their grief,” rounded out his vision.

“People of color come in many different hues, many different body shapes, and all of them are celebrated through their lens,” Cofield said. “I was so taken aback by their passionate commitment to regaining their own narrative and tell beauty through their lens and not have it be dictated by an outside influence or an outside culture. I find it extremely powerful when marginalized voices regain control of their narrative.”

Alexandria King, who played the title role, said that doing this version of Antigone in Harlem makes the piece even more powerful.

“I think black people are a revolutionary people, and are greatly oppressed in our country,” King said. “And yet to be black is to be gifted, to be blessed beyond measure, with so many wonderful truths, and we’ve come past so much. To perform [Antigone] in Harlem, it speaks to the truth of who we are, that we do not give up, we will continue to fight for our equality in this world and through our art, we can confront these issues head on together and heal as a community.”

Jones, Cofield, and King all said that they are glad that the conversation will continue this fall, with Harlem Stage and Theatre of War’s Antigone in Ferguson.

Just a few blocks down and two months later, Antigone in Ferguson, an adaptation of Antigone conceived in the wake of Michael Brown’s death, will have its first sit-down, long-running production. Originally produced in 2016 at Brown’s high school in Ferguson, Mo., it aims to bridge divides and heal the trauma of police violence and racial injustice. It features a rotating cast of actors in a dramatic reading of the play, including Samira Wiley, Paul Giamatti, and Tamara Tunie, and uses gospel music composed by Phil Woodmore that will be performed by a live choir of activists, police officers, young people, concerned citizens from Ferguson and New York City, and rotating Harlem choirs. Above all, audience discussion is the main impetus of the production, which is not a fully staged production.

To Doerries, Antigone in Ferguson is not just about Ferguson—it’s about something bigger than that: a shared humanity. “It’s a production that brings together a group of people who are deeply connected and were all deeply impacted by Ferguson, and then starts a conversation,” he said. “We’re extending the platform to other cities because Ferguson has come to mean so much more.”

Since the original production, it has toured all over the world: to Brooklyn, Baltimore, the university circuit, and most recently Greece. Harlem Stage will present Theater of War’s production Sept. 13-Oct. 13. The five week production is the longest run either company has ever had. Harlem Stage xecutive director Patricia Cruz said Harlem Stage wanted to be the venue for this piece because it was right in line with the company’s mission of doing exciting works that make you think.

“It’s a project that is very important to be done at this point in history,” she said. “It’s really looking at the issues of how individuals and groups can respond to power that can in fact be harmful to the moral values that we hold and looking how that is manifest by the kind of conflicts that have risen between police departments and communities of color around the country.”

Doerries believes that the central conflict of Antigone can resonate with audiences of different perspectives. “What I love about what Sophocles does in Antigone is that all the characters believe they are right,” he said. “We’re talking about life and death questions. It models and reaffirms what’s at stake.”

“Within the music itself, we can really dig into the depth of this story,” Woodmore said. “I wanted to create art that is transformative, open, and honest.”

One particularly transformative moment, according to both Woodmore and Doerries, happened after the Manhattan production in 2016*. During the post-reading discussion, local choir member Marcelle Davies-Lashley spoke with police officer Lt. Latricia Allen; both had sung as part of the choir. At first Davies-Lashley made her distrust of the police clearly known, saying, “I don’t have a lot of love for the police.” By the end, the two women were holding each other and crying with each other.

“Each performance, each discussion is different,” Doerries said. “It heals very deep divides and really shows the human connection that is possible.”

With these two Antigones, human connections extend from company to company and beyond. CTH and Harlem Stage mutually support each other in a neighborly way, according to Cruz, often alerting the public of each other’s programs and listing them in e-blasts. “We are a community, and with that we rely upon one another,” Cruz said.

Jones has worked with Theater of War in the past, and at the beginning of rehearsals for CTH’s Antigone, he invited Doerries to visit a rehearsal and speak to the CTH cast about Antigone in Ferguson. The two have discussed the piece together, opening up dialogues with each other in the same way they hope audiences will keep talking and keep the conversation alive.

“A takeaway from my conversations with Bryan was that the reason why Greek plays resonate 2,500 years later is because they are meant to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” Jones said. “Black communities and other marginalized communities have been afflicted socially, economically, and politically for centuries.”

“We view it almost as a complementary effort,” Doerries said of the CTH Antigone. “I love the spirit of Classical Theatre of Harlem—I love that it shares our values, the fact that you can just walk into the space and don’t need a tangible ticket.”

Accessibility is a vital component of why both CTH and Theater of War Productions do what they do. CTH’s summer shows are done outside for free—which draws a diverse crowd. “It brings together audiences that have no agenda other than seeing art come to life,” Jones said. “I’m proud to say that we have the most diverse audience in New York City.”

One audience member stuck out to Cofield. A little boy who came to the last Saturday night performance with his father sat through the whole show, enraptured despite a torrential rain, then came back the next day for the Sunday closing performance, bringing along his mother.

“To see a five-year-old boy from the Bronx get so fired up by theatre—to me, that is the beauty of what we do, and I don’t take it very lightly,” Cofield said. “Hopefully, we’re exposing the next generation of theatremakers, or even just opening up opportunities for young people to think differently about art. That it doesn’t have to be one way. That there is a place for them and they should not feel intimidated by classical work.”

Theater of War Productions presents all of its work free to audiences as well. Because Harlem Stage is a smaller space, there will be a system to reserve the free seats. But Doerries still wants as many people as possible to be able to come and be part of the dialogue. “We want to make sure the audience is really in the room,” he said. “The discussion is not a talkback—it is the performance. We don’t think that discussions should be monetary or ‘consumed.’”

In fact, half of the seats (about 90) will be offered to individuals, groups, and communities who will receive transportation and dinner in addition to the performance. The other half will be available to the general public. According to Cruz, Harlem Stage is engaging in huge outreach at community boards, local churches, and public schools that the company works with on a regular basis to ensure that they know that they are special, invited guests.

“We’re opening the doors of Harlem Stage and the Gate House,” Cruz said. “This production and its accessibility allows us to do the work we’ve wanted to do. We want to build a community within a community.”

During his post-show speech to the community at CTH’s Antigone, Jones spoke about Antigone in Ferguson. “If this performance stirred a desire to talk, go continue the conversation at Antigone in Ferguson this fall at Harlem Stage,” he said.

He also referred to the insert placed in every audience member’s program that spread the word about Antigone in Ferguson.

“I’m glad the conversation is continuing and allowing for further discourse,” Jones later said. “I think Bryan and myself are like-minded in that we assert our art is a reflection or an extension of what is happening in the world. I hope our work encourages folks to think critically rather than criticize thinking. Antigone is the appropriate platform to ignite that very conversation.”

And what were his triumphant last words to audiences after every performance? “Let’s tell the world what’s happening in Harlem!” Indeed, history is happening in Harlem.

The Classical Theatre of Harlem presented Antigone, inspired by Paul Roche’s adaptation from the classic Greek tragedy by Sophocles. Direction by Carl Cofield, producing artistic direction by Ty Jones, choreography by Tiffany Rea-Fisher, music direction by Kahlil X. Daniel, dramaturgy by Shawn René Graham, scenic design by Christopher and Justin Swader, costume design by Lex Liang, lighting design by Alan C. Edwards, sound design by Curtis Craig, projection design by Katherine Freer, props design by Samantha Shoffner, and assistant direction by Amandla Jahava.

Theater of War Productions and Harlem Stage presents Antigone in Ferguson. Direction and translation by Bryan Doerries and music by Phil Woodmore.

*A previous version of this story had the wrong location for a pivotal performance of Antigone in Ferguson. It’s been corrected.