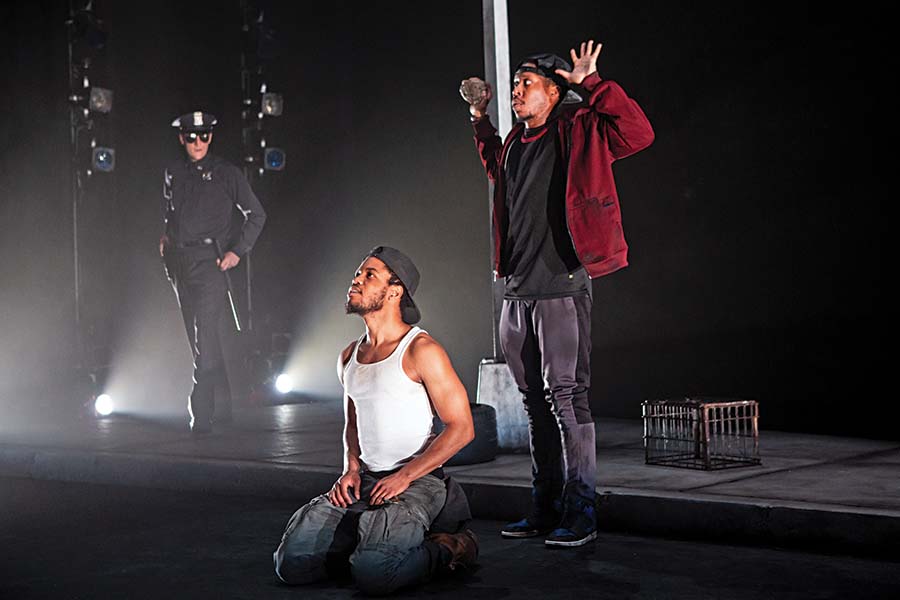

In Antoinette Nwandu’s new play Pass Over (published in its entirety in the September 2018 issue of American Theatre) two young black men, Moses and Kitch, hang out on a purgatorial street corner, alternately anticipating and plotting an escape from their circumstances, with occasional visits from an oblivious white man, Mister, and an aggressive white cop, Ossifer. But like the tramps in Waiting for Godot, their hopes are unrealized. Natasha Sinha is Associate Director at LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater, where it was produced over the summer.

NATASHA SINHA: What I’m most struck by in this play is how you identify something so deeply rooted in the fabric of America, and then you channel that through layers of theatricality to tell the story of two black men being hopeful, terrified, playful, entirely human, and unsurprised by the traps and the biases they face. Can you talk about how you landed on these characters and the constructs of the play itself?

ANTOINETTE NWANDU: The characters are super-loosely inspired by young men I had been teaching at the Borough of Manhattan Community College; also by the murder and then the trial of the murderer for Trayvon Martin. And as far as the constructs, one of my creative impulses is that I’m very drawn to the different ways that we create epic. One way is by making a play’s surface area vast—whether that’s huge ranges of time or tons of characters or locations. But with this play, I was like, how can I keep the surface area of the play small but give it very deep roots? When you compare contemporary young black men on a street corner to young slaves to young Israelites, what essential truths can we distill from all of these different historical moments?

The play’s tone smash-cuts from clowning to harsh reality, the use of repetition plays a big role, and you create a modern environment that’s steeped in realities from both biblical Egypt and a Southern plantation. Did you feel like you were trying to connect the characters to those sources in sort of a puzzle fashion while you were building a world that takes place on an urban street corner?

I think puzzle is a really great word. A lot of the times that’s how I describe my writing process, creating a puzzle for myself, and then the process of building the play is figuring that puzzle out. I did start with a lot of—I wouldn’t say rigid, but a lot of clear identity markers and demographic markers from these three layers of history. I was always very clear that these men were standing on the sedimented layers of history and that those identity markers were rising up into them and through them. One of the huge puzzle pieces I had to think through was, is Moses a literal reinterpretation of the biblical Moses, for instance? Or is he a young black man who knows what the biblical Moses means and then happens upon a version of that power for himself? Is this a world where the Bible actually exists and he’s drawing on something self-consciously? Which is what I eventually landed on.

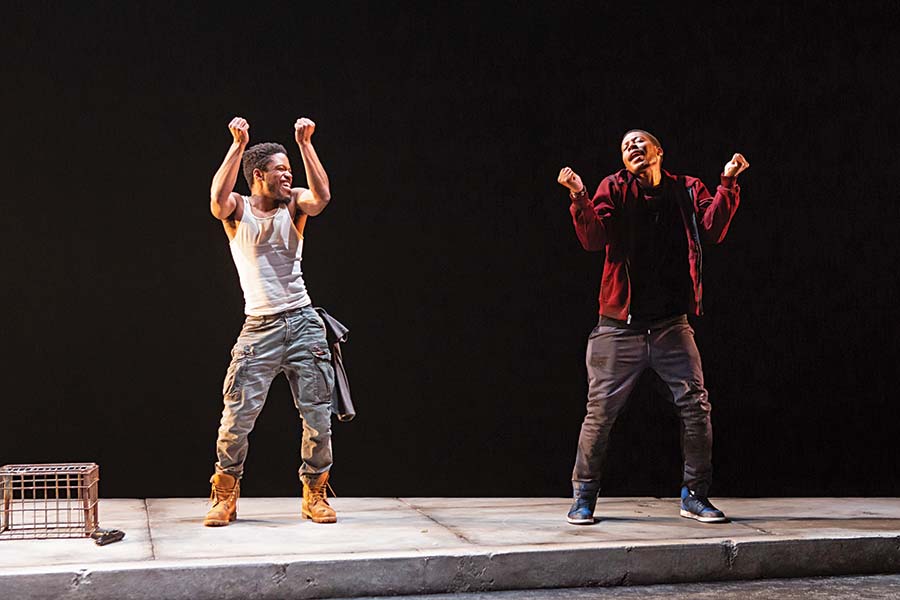

Thinking of Moses and Kitch, what role, if any, does radical joy play in Pass Over, and maybe in all of your work? I’m thinking of those radiant moments of dancing and silliness between Moses and Kitch, and the big climactic moment of justice before the ending. The ability to see that imagined onstage is so powerful.

I think the playfulness of the characters is partly just their age—they’re young men coming into their own who I would barely think of as adults in the first place. That said, I do think there are crucial moments of intentional joy, of choosing to be hopeful as a means of survival. The radical nature of that act, of that choice, is a form of resistance—of continuing to promote and honor your own humanity when every single voice and person says you’re not a human. To say, “No, I choose joy in this moment for myself, I choose to create my own reality, I choose to be hopeful in this moment”—those are incredibly defiant acts.

At the end, when Moses and Kitch get to that moment of levity, it’s a bit more spontaneous, like they’re not choosing joy to cope with the mess of their situation and the mess of their country, but it’s like, “Oh, something has actually changed—I genuinely feel hopeful and happy right now .” I think that’s very evocative for anybody who remembers the previous administration. The joy seemed a lot more spontaneous, like the natural course of things.

Systemic racism seems to be finding its way into the spotlight these days, though, of course, it has always existed in America. Oppressing black bodies, the casual default of white supremacy–all part of what brought us to this moment, and also to the final moments of the play. Why didn’t you want Pass Over to end with the moment of joy? Why did you want it to go further?

Emotionally, yes, it would have been wonderful to end with Moses and Kitch literally getting off the block. Kind of like giving the audience an emotional high-five. But I wanted to root out, in myself first and foremost and then in every audience member, this notion that just because we, as a nation, did one sort of morally cool thing—I think we can very narrowly call voting for Obama a moral good insofar as it pushes back against the notion of the black body as merely property—but just because we did that, or because half of us did that, it doesn’t mean there isn’t still pus in the wound. Emotionally, sure, every time we rehearse it, I’m like, “Why can’t we just do lights out here?” But then it’s like, “Why can’t Trump just not be president?”

Also, on a macro scale, the structure of the play tells a pretty macabre joke: Let’s say that a miracle happened tomorrow and a Moses-type figure were able to call down plagues to eradicate the police state in the United States as we know it. So the state-sanctioned murders of black people, people just like me, whose murders are on my mind in some capacity every moment of every day, just stop. That would be amazing. A true miracle. But then I’d still have every other white person to worry about, you know what I mean? All the ones who aren’t wearing a uniform. At least a police officer announces their power with a badge. But if I’m walking down the street, I’m like, in an anonymous crowd at any given time, half of the white people I encounter voted for a man who literally wants to disappear the laws that ensure my equity in this country. And increasingly, we hear accounts where many of them are taking it upon themselves to make it happen, either by calling the police unnecessarily or directly committing violent action. So that’s the shitty joke of it: Yeah, it would be great if we could dismantle the police state. And then we’d have everybody else.

It’s not a play where you get uplifted into this dream moment and everything’s perfect and then you leave. And that’s not at all to disparage those kinds of plays! But your particular way into storytelling holds a mirror up to the audience and forces folks to see ugly truths.

Absolutely. I know who I am and I know what my job is. I’m grateful when there are other writers, especially writers of color who, in this moment, it seems like their job is to bring joy and to bring those positive endings. I need those plays as much as anybody else, because I know that right now in this moment, that’s not what I’m doing with this play.

Tangentially, I think that’s part of what we miss out on: the diversity within “diversity.” Whenever I say “diversity,” it’s always in quotes, because I don’t fully understand what it means to many white theatre folks beyond a buzzword. The “diversity” conversation is flattening, and we don’t get to really dig into the fact that, yes, of course, there are some plays by black playwrights that give you a positive uplift, and then there are plays like Pass Over that don’t let “allies” off the hook, and also there are countless other kinds! What do you think is missing from the “diversity” conversation, or what would you like to see as the next step?

I feel like the diversity conversation gets strangled because we think about diversity in capitalist terms: “Okay, I have a benchmark. I’ve got to have three of those to get that money over there.” Not that I have the power to make people think morally or critically about equity, about justice, about words that actually have to do with many of the old religions and wisdom teachings from all the around the world, this very simple idea of the Golden Rule and treat other people the way you would like to be treated—but I think that’s where all of these “diversity” conversations fall flat. We’re looking at benchmarks and checklists instead of how we actually treat people who are different than you, how open you are to hearing their stories. And yes, that difference does exist within these broadly devised demographic markers. I think any time you attempt to solve questions of inequality using means that are also driven by that inequality, like capitalist means, then the conversation is going to stagnate.

Then where would I love the conversation about diversity to go? I do think, especially in theatre, we’re language people, and I think language matters. There are a few things that I long for and that I hope for. A couple of days ago, for instance, I went with two other black women to Brooklyn Museum to see the poet and playwright Claudia Rankine in conversation with the visual artist Alexandra Bell and Doreen St. Félix from The New Yorker. And while we were there we ran into another black woman, all of us working in theatre, in entertainment, in different ways. And the conversation was about whiteness and specifically the Racial Imaginary Institute that Claudia Rankine is very involved in. Anyway, I’m sitting there and it’s this very intellectually stimulating conversation about whiteness and what whiteness is. But it’s also like three black women onstage, and I’m there with two black women. We run into another black woman while there. My question, which I didn’t even get up to ask, is, where are the white people? Where are the white artists who are grappling with their own whiteness?

One of the things that kept coming up during the conversation, and is obvious in my play, is that whiteness is experiencing a schism right now. It’s in identity crisis. What does it mean to say, “I believe in white culture,” or, “I have white culture,” or, “I’m proud of white culture”? You know what I mean? Are you a white supremacist? Are you a white person who completely dissolves and disappears into another culture? Are you just a capitalist? Is being white just like American Psycho: You’re just a capitalist who doesn’t give a fuck about anything but making money? What exactly is whiteness? How do we tease out the performance of whiteness? How do we think about the power structures within whiteness? How do we deal with the immigrant thing, that people who weren’t “white” 50 years ago are all of a sudden white now? Is that what the American Dream really is, being able to call yourself white?

I want the “diversity” conversation to start including white artists who are grappling with their own whiteness, which would mean, I think, relinquishing the term “ally,” which I’m pretty much done with. Because I’m like: No, no, no, I don’t need you to be an ally in my fight. I need you to take full responsibility for your place, your part, and your responsibility in this shared American question. I don’t own the race conversation. It’s yours as much as it is mine. We’re still in the place of, “Oh, ally, ally, ally, I’ll march with you, I’ll be sad with you.” You know what I mean? I don’t need an ally, actually. I’m doing okay. I need you to come in and talk to me about your whiteness. Struggle with it. Admit it exists as a construct that makes life much easier for you. I want to see that play. I want to hear that poem. You might “get it wrong.” It might be really confusing. It might be 30 minutes of silence, I don’t know. But I want someone to pick up the mantle who is white and needs to deal with whiteness. I’m waiting. I’m waiting.

The final monologue of the play is so stunning because of the way you confront the audience with this immense failure of “good intentions.” Can you talk about how you landed on it? It developed further during our LCT3 rehearsals, and to me, it speaks to the timeless and casual reality of racism.

The first version of the monologue, which I imagine is maybe the more widely seen one, since it’s now on the filmed version of the Steppenwolf production—that was so specific to that summer and that moment. At that point the whole Trump thing was like six months old. People were marching every weekend; there was this sort of white-hot rage that felt very apropos to that moment. Then a year passed and I took another look at that rage and that sort of “hit them over the head with a sledgehammer” and “it’s you.”

For the new monologue, to be perfectly honest with you, I remember thinking about my own privilege. We’re in the middle of one of the most egregious transgressions against immigrants and refugees, for example. And I’m a citizen. I hold an immense amount of privilege because I’m not directly targeted by that. So I had to tap into some of the worst feelings that that privilege begets. It’s like, even in those moments where you’re writing a character who’s so abhorrent—”Oh, I hate this guy, how could I even be in his mental space?”—I was able to find his humanity, because I obviously had to connect it with my humanity. That’s the only way it’s going to happen. Holding space for that humanity, I think, was the kind of scary but necessary step in the evolution of that monologue.

Do you want to talk about the future of the play and in what kind of spaces you hope to see it produced?

I mean, what can I say? I hope this play goes to every city in the United States. I hope it goes to big regional theatres. I hope it goes to small theatres. I hope it goes to theatres in majority-white cities where they have to fly in black actors from other places. I hope it goes to college campuses. I hope it goes to high school campuses, though I think that that would probably be a little bit harder, ’cause parents would probably go crazy. I hope it goes overseas. I hope it goes to the U.K. I hope it goes to, I don’t know, Australia. I really want it to go to Israel and Palestine. I would love to know what this play would do in cultures and communities that are not defined by the black/white binary but who have their own binaries.