This story is part of an issue about abuse, harassment, and sexism in the theatre. You can read other #TheatreToo stories here.

In December 2017, Texas arts website TheaterJones published an article detailing allegations that writer/director Lee Trull had used his power to sexually harass young women in the local theatre community, costing him his job as director of new-play development at Dallas Theater Center. Katy Lemieux spent more than a year working on the piece; this is the story behind that story.

The shrill sound of the ringtone jolted through the sleeping house. I knew it was coming; still, the blare of my usually silenced phone caught me by surprise. Crises tend to happen when it’s inconvenient. Never on a lunch break or a quiet evening while scrolling Instagram. I had turned my ringer on and slept fitfully as I waited for the call.

“He’s going, you should come now,” said the somber voice of our beloved nurse on the other end of the line.

I threw on shoes and raced out the door in pajamas. Performing necessary and routine tasks in the midst of a panic is jarring. Start the car. Yield. Sign your name on the visitor’s log. Take the elevator to the fourth floor. Pass the nurse’s station and enter the room. Earlier that week my dad had joked that we should bring a game to play while we waited for his life to end. “Would that be macabre?” he mused.

It is something not unlike impatience, abiding death. No one wants to hasten the last moments you’ll ever spend with a person, but those agonizing days are blurry and fluid. Time is not quite suspended, and yet it is.

My father would not die for another 21 hours. My sister and I sat together and waited throughout the night. The “death rattle” had set in—a new term I learned once he became unresponsive and his breathing raspy and rhythmic. My mom called him the “percolator.” A sound that signals looming death can become oddly meditative. My stiff back and neck ached against the hospice recliner. As the morning light broke over downtown Fort Worth my mind began to wander.

I wonder what Lee is doing. I wonder if he knows.

Of course Lee knew.

Two weeks before I had scheduled a meeting in my home. The women who I knew to be Lee Trull’s victims were ready to get together. What was the action plan? What could we do now?

I didn’t want to write about it. Surely I could get everyone set up, determine a new point of contact, and then wash my hands of the whole thing.

It all started months before I found myself in that hospice room. I trace it to Kieran Lynn’s weird little play Crossing the Line, produced by Amphibian Stage Productions in Fort Worth, about a couple examining boundaries, both emotional and physical. My husband, the actor Justin Lemieux, came home from rehearsal one night in July of 2016. One of his castmates, Kelsey Milbourn, had told him she’d once received a lewd text message from Lee Trull, then casting director for Dallas Theater Center, when she was 19 and a freshman at Texas Christian University, and she now refused to ever work with or near him again.

I knew that Trull had been recently promoted to director of new-play development at DTC—the only LORT company in North Texas, one of only two in the state. The news of his behavior toward Milbourn came as a shock to me, but something about her story urged me to look a little closer. I didn’t even know Kelsey at the time, but I sent her a Facebook message.

What unfolded from that first message was a long and complicated ordeal, which is the only way I can express what the last two years have been.

My family is deeply embedded in the Dallas-Fort Worth theatre community. My husband was an SMU MFA graduate as this began to take shape; at the time I was grants manager for the Dallas Opera, housed directly across the street from DTC. I knew as well as anyone how Trull was connected to the university’s theatre program. The theatre center provides a two-year company position to one member of each graduating class of the MFA Acting program; Trull attended season auditions for graduate and undergraduate students at SMU as a representative of DTC, and at times he was the sole representative present. DTC frequently hires undergraduate and MFA acting and design students. His presence at the school gave him the ability to allow or deny its students entry to the prestigious stage of that now-Tony-winning theatre.

I confess that I too had hoped for Trull’s attention for my husband. “Ask him to get coffee!” I once urged. In short it was impossible to live and work in this community and not know the influence Trull had. As the wife of a Dallas actor and the theatre correspondent for the Dallas Observer, I knew this to be true from many interactions and interviews with theatre professionals.

It is because of this web of close connections that I worried about getting involved in reporting this specific story. I worried, for one, that it might damage my husband’s professional connections. And it would deeply complicate my professional relationships and friendships with scores of actors, producers, and directors in town: Are we friends? Colleagues? Do you think I’m talking to you just for the dirty details? Do you trust me? Can I trust you?

But I found I couldn’t avoid the story. Every interview I conducted in the theatre scene during that time was tinged with reporting on Trull. I wanted information from everyone I spoke to on what they knew, and who else knew. Sometimes the bait was taken heartily and readily. Discussions with female playwrights, actors, and directors often very naturally led to the subject of sexism. I guided conversations about access and representation to sexual harassment.

“Have you ever experienced anything in this town that made you feel weird…?” I’d casually slip in. The response was often a shift in tone, and a mutual understanding that this was now about specific instances of harassment. “I know who you’re talking about.” So many women repeated this statement.

Eventually I got bold enough with friends to talk about it openly, and I put out a call through a friend who was an SMU grad and very connected to the alumni community: Get at me with your stories of sexual harassment. I never said Trull’s name. I didn’t need to.

Soon after I got an email from Katy Tye, co-artistic director of Dallas’s Prism Movement Theatre, and an SMU graduate. She’d experienced gender bias and harassment many times, as people assumed she was the girlfriend of her co-director. And she had a story about her time as an undergraduate student and a sexually explicit Facebook message conversation with Trull. She had saved the screenshots.

This was it, I was sure of it. Here was proof. I was emboldened to do the work now, though I had no roadmap or guide. I partnered with several other Dallas writers, women who knew just as intimately the stakes and the score. I reached out to Aimee Levitt, the journalist who helped break the Chicago Reader story about the history of abuse at Profiles Theatre under the hands of Darrell W. Cox. She gave me some names to contact, including Laura T. Fisher and Lori Myers, who co-founded the Not In Our House movement in Chicago and thus developed the Chicago Theatre Standards for theatres to circumvent and report abuse. Aimee’s advice: There is safety in numbers and lawyers. Lori guided me to ask the women exactly what they wanted to do about it; what I wanted didn’t matter. Maybe these victims wanted to walk away and never think about this again, and that had to be okay. (That option was secretly a little appealing to me.)

By October 2016 we had a meeting set with a group of women who had experienced harassment from Trull, including Katy Tye. I tried to be as careful as possible: I blind-copied the survivors on the emails so they wouldn’t know about each other. I didn’t even attend the meeting, which was held by a friend offering her home as a safe space. I didn’t want them to feel even remotely that a writer in the room could make them unsafe or expose them.

Somehow Trull knew. On the day of the meeting I received a text from him: “What are you doing in the Arts District? I saw you walking today.”

I had seen him that day on my lunch break as I walked past the theatre center. I avoided him by looking at my phone. I was terrified that somehow he knew. But who would have told him? We had been so careful not to expose anyone’s stories. How could he know there was a meeting that very day? Maybe he didn’t know, and it was a weird coincidence. But Katy Tye also happened to receive a text that day too, and then his donation to her theatre company.

Now the stakes were higher, and we were all scared. I could not offer anonymity in the ways I had hoped. I was not a protector. The Dallas Opera and the theatre center share a parking garage. Every day I would look for his car, worried that I might end up alone with someone who knew I was out to expose him. The times I happened to see him paralyzed me with fear. What at one time might have been a hello or stiff chit-chat turned to a curt nod, and finally no acknowledgment whatsoever. I felt like a coward, terrified to even hold eye contact with him.

Little action was taken again until December, when we organized a second meeting at my home. This time I involved some women I considered to be leaders and advocates in the theatre community. But by mid-month I had to cancel the meeting and prepare to admit my father to hospice. He died two weeks later.

That marked an end point, and I wasn’t sure if there would be another chapter in this story. By the new year I was too consumed with grief and too overwhelmed with the minutiae that comes when a parent dies to think about anything else. Every minute of my free time—and many minutes of the time I was supposed to be working—went to straightening out the mess my father left us in his wake. (Including a woman we learned had been his stalker.)

Still, the Trull project was never far from my mind. I lived in near-constant paranoia that my plan had been exposed. I suspected that many in the community knew what I was up to (I would learn later that yes, they did), and I worried what this might mean for me or my husband professionally. I was aware that I was now walking a dangerous line between reporter and advocate. And I was starting to realize how many people wanted nothing to do with this, including one of my investigative partners. I worried that everything I was doing had been wrong. Remember: Harvey Weinstein was still not yet exposed. There was no clear guide for this, and the national conversation was still months away.

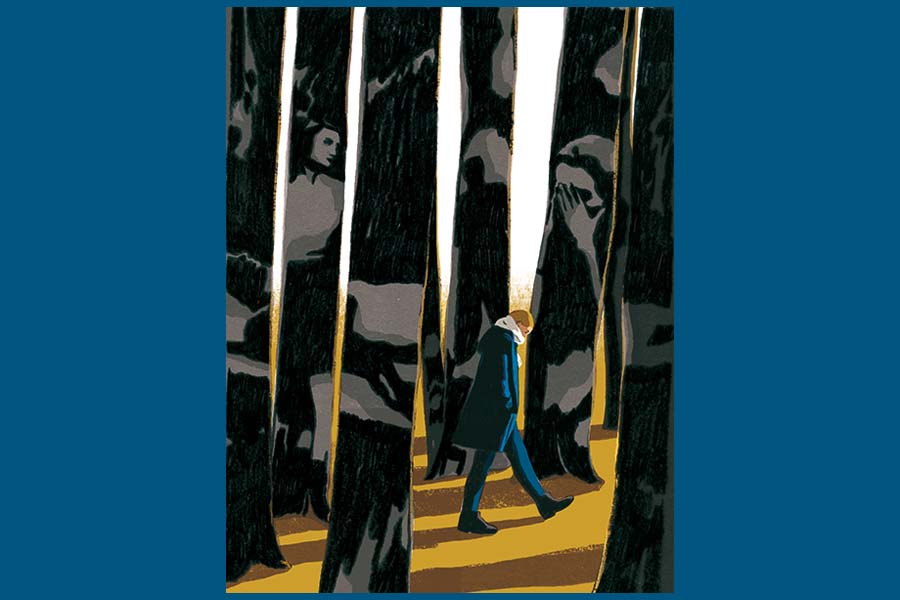

I felt like a voyeur living in lurid stories that were not my own. I was drawn into them, felt their insidious power consume me. They made me so angry that I found it hard to think about anything else. I could not fix the problem and worried that the fight was lost. Meanwhile I was still receiving new allegations about Trull’s abuse. I tried to hand off the story—all of my sources, my documents and pages of notes—to editors I knew. No one wanted it. Too risky, they said, and the women’s stories, though numerous, were not enough proof in themselves.

By spring and summer of 2017 the investigation had halted. I stopped talking about it and let my communications lapse.

I felt a guilt that took my breath away at times.

And still it nagged me. Still it crept into my dreams. My grief over my father’s death had morphed into something weird. I cannot separate the death of my father from this experience. Like one of Pavlov’s dogs, whenever I hear the bell of Lee Trull’s name or see his face, I cannot help but feel overwhelming sadness. It is a failure of my brain and heart that I have linked these two terrible experiences together.

As the summer of 2017 gave way to autumn, something changed and I had a chance to act. In the fall of 2017, Shelby-Allison Hibbs, a theatre professor at the University of Texas at Dallas, contacted me about a series of essays she was working on about sexual misconduct in the Dallas/Fort Worth community. By now Harvey Weinstein was a household name and #MeToo perpetrators were being called out daily. I was rejuvenated by Hibbs’s dedication, and the moment seem opportune. Mark Lowry, the editor of the website TheaterJones, joined Hibbs and myself, and we spent a furious six weeks putting together a roadmap from the puzzle of nearly a decade of abuse stories. We triple-checked each story and corroborated the sources. Mark assembled a team of lawyers to guide us through it and to protect survivors from any fallout that might arise.

Around that time a woman I had first tried to reach in 2016 responded to my message. I wept and held my phone with wavering hands as I read her statement. She told me her story again that night over the phone through shaky breaths and tears. She said she was revisiting a terrible trauma in the hopes that we could stop Trull. I have never breathed her name to another human being apart from my co-writers. My heart stopped when I read her words, and the fierce desperation that I now know to be akin to when one of my children is hurt broke me down. We had to stop him.

On Dec. 4, 2017, Lee Trull was fired from Dallas Theater Center, a year and half after my husband’s conversation with Kelsey Milbourn. TheaterJones reported the firing, with a statement from DTC, saying the “full story” was “coming soon.” The next day TheaterJones published our multi-sourced report. By then we had more stories than we ever could have imagined. Every publication in town followed up on the story. Laura Fisher of Not In Our House traveled to Dallas to lead a public discussion about sexual misconduct in theatre. More than 100 members of our local theatre community attended.

Trull did not respond to Mark’s request for comment and went effectively silent. But four months later rumors crept back into the community. He was preparing a statement. He’d hired a PR firm to help him rebuild his image. I did not know what was true, but soon we would all find out: He had contacted The Dallas Morning News in response to their request for comment on the story in December. He was ready to talk. Perhaps he was ready to atone.

I initially found Sarah Mervosh’s Morning News story to be a fair and honest examination. But it didn’t sit well with me. Ultimately I’ve come to believe a gratuitous profile of a sexual abuser to be gauche at best, damaging and triggering to survivors at worst. The story got a lush spread in prime newsprint real estate and an interactive feature online, with Trull’s face glaring out at the reader. Few of us who spoke out against him were quoted. And a firsthand account alleging that Trull raped an unconscious woman was glossed over in an uncomfortable he-said-she-said sort of way.

Mervosh did hit on a theme that I’ve asked for a long time about my own father, even before he died: What do we do with men like this?

My father was not a sexual predator, abuser, or anything even remotely of that nature. He was a lifelong addict, frequently hovering around sobriety. His attempts to quit were always cold turkey and always horrific. If you’ve ever experienced an addict trying to detox you understand this. My father eventually traded his addiction to synthetic opioids for Suboxone, the “blockbuster” drug meant to aid opioid addicts through withdrawal. He then refused all pain medication, which nearly got him kicked out of hospice before his death.

I’ve often mused about what should happen to men like this. Men who betray our trust. Men who hurt their families through selfishness. Since my father’s death I have learned what happens: We just go on with our lives. The memories come whenever they want, and the many consequences of being a child with an addicted parent are ours to deal with the best we can.

My father was also a gifted storyteller, hilarious beyond all measure, and an artist whose 200-pound wooden bear sculpture now adorns my patio. He was a teddy bear bleeding-heart dad of two girls and three granddaughters, and he broke our hearts over and over and over.

From an investigative point of view, Trull’s story had the outcome we wanted, and the result we needed. As I walk down this path in my mind and revisit each avenue, picking apart conversations, I remind myself that we did something right. But it is a terrible, gnashing, complicated victory. When a person’s wrong deeds are exposed, the fallout feels unending.

For the women, the survivors, the hours spent living in these stories aren’t quantifiable. They must simply be part of the process of living.

When a person is dying, every day has the potential to be an emergency. An action plan is always in place when preparing for the worst. But those breathless moments fade and our shoulders slacken as the storm passes. Now we are marked by this pain. It becomes a part of our DNA, coloring the lens through which every moment of the day is viewed. Are we—as readers, advocates, writers, survivors—doomed to perpetually respond to the words and actions of sexual predators in a similar way? Must it always consume our minds? Where do we make the head space for grief and anger after the emergency has passed?

Years before his death, my dad apologized to us. His recovery was open for discussion and we talked about it all the time. But he never self-righteously asked what he was supposed to do to go on with his life. He was well aware that he had done irreparable damage to us as a family, to himself, and to countless other relationships. He didn’t test the waters to see if the time for atonement had passed, if we had forgotten. But he asked me on one of his last good days how I could ever forgive him.

He shook his head and mouthed “no” seconds before he died. I took his hand with an absolute and terrified fury and said, “We had a good life. I will see you again.” I will spend my life continuing to wonder if those words are true.

Katy Lemieux is an arts writer based in Dallas.