We’ve always relied on great images to help tell the stories we publish in American Theatre, from headshots of theatre leaders to production images provided by theatres to original photo shoots (as well as occasional illustrations). When we launched a full-time website in the fall of 2014, that exponentially multiplied not only the number of stories we were able to publish but the number of images we needed to gather and place to accompany them. To give you an idea of just how many posts we’re talking about: In the 150-plus business days that have passed so far in 2018, we’ve posted 590 stories on this site. That’s an average of nearly 4 per day. Each story needs at least one image, and some need several.

We get most of these images from theatre press agents or from theatre websites, but we also get a fair amount from such services as Photofest, as well as our own digital and hard-copy archives. You may have noticed that our standard captioning protocol, as in any other publication you could name, is to tell you who’s in the photo, where and sometimes when it was taken, and who took it. Of course, many production photos also clearly show us sets, costumes, lighting, props, and projections. Doesn’t it make sense to also credit the folks who made those things? And would there even be an image of the show at all without the contributions of the whole creative team, which includes the director, the sound designer, and the stage manager?

This was the argument made to us last month by members of United Scenic Artist 829 (which comprises theatrical designers of all kinds), articulated in an open letter posted by sound designer Elisheba Ittoop, written with her design colleagues on the Guthrie Theater production of West Side Story. They wrote in part:

ATM purports to be “the nation’s only general-circulation magazine devoted to theatre.“ In the American theatre, designers are acknowledged to be core creative team members. When ATM denies credit to designers while simultaneously highlighting photos of our work, they minimize the role designers play in a production. Not crediting our work diminishes designers’ contributions to a production, denies them publicity and exposure that is rightfully theirs, and further minimizes the value of good design to theatre producers, directors, playwrights, and other theatremakers.

The letter also referred to an ongoing struggle to get The New York Times to list designers at the end of theatre reviews, a controversy we weighed in on at the time, and called on American Theatre to exercise its own leadership in the field. If not us, then who?

Our initial response to this full-court press campaign, as a small staff with a sometimes overwhelming workload, was not especially warm—and not because we don’t love and admire designers and their work. We had just that same week launched an entire special issue on lighting design and put two legendary lighting designers on our cover (a first in my memory), and we publish a regular column on designers and their work. Tune up your tiny violin if you like, but gathering and properly labeling photos for the aforementioned 20 weekly posts was already one of our less favorite chores—and now we were being asked to do more?

But there’s a kind of criticism I’ve come to recognize as a compliment—the kind that says, essentially, “American Theatre is better than this,” and holds us to high standards of accuracy, probity, circumspection, and authority. Put another way: If folks didn’t care about what our magazine is supposed to stand for, would they even bother to call us out? I damn well hope they care, because we certainly do. Whether we can live up to all those expectations is another matter, but I don’t take for granted the position we hold and the great responsibilities it carries.

So, after some consideration and conversation with my staff and with the designers behind the open letter, we announced a new policy that a) isn’t particularly difficult to implement, and b) addresses much of designers’ concerns. It is this: that when we write a story about a single production (especially but not exclusively like this regular feature), we will include a list with the names of all the creative team at the end of the story, in print as well as online. As Ittoop and others acknowledged in conversation with me, they weren’t expecting us to cram the equivalent of a playbill into each photo caption but to give credit where it’s due—and the “where” in our case may be in a listing in the story, not in each and every photo caption.

As for stories with images from multiple productions—like, say, this one or this one? (Not to mention this regular feature.) That’s going be a tougher nut, not only in terms of workload and logistics but print space. Perhaps we could rethink our every-story-needs-a-photo m.o.? The internet is already awash in photos, scantly credited and sourced (Chance magazine founder Fitz Patton said as much to us years ago, memorably calling the internet “the Sargasso Sea for great photography”). But the economy of digital attention, particularly in shares on social media, all but requires a photo as the price of entry. I’m not sure we’re equipped to be leaders against that tide.

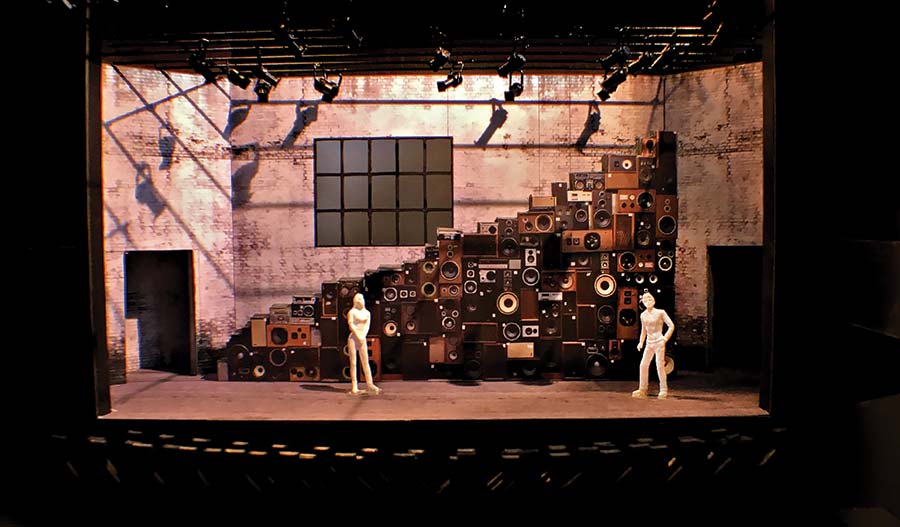

But we do feel called to leadership in recognizing and celebrating the work of theatre’s underpaid, under-recognized artists and craftspeople. In addition to the policy change announced above, we convened an advisory panel of designers to talk through this issue, and to broach other topics about the field that we should know about. It was a constructive, even collegial conversation. Consider our awareness raised all around. As I told scenic designer Christopher Acebo, another organizer behind the open letter, American Theatre may not be able to change our whole caption-credit policy overnight. But going forward, when we’re considering a photo whose impact owes a clear debt to theatrical designers, why wouldn’t we at least also consider tracking down credits for what we’re looking at? (And while I’m on this point: Theatre press agents, please include all these credits with your photos. More details on our photo specs here.)

Recording and reflecting the work of the field’s theatremakers is what we do every day with our editorial coverage—it’s literally our job. What has become clear is that we’ve been a bit too cavalier with the images we use to illustrate that coverage, and about the hard work of those who make those images possible. If a picture is worth a thousand words, we can certainly repay at least some of that value with some words of our own.