On their first pit stop, with the air as sticky as boiled peanuts sold at a roadside shack, a cherry red minivan stuffed with four playwrights and one artistic director pulled over between Montgomery and Mobile, Ala. They were out of gas. Another problem: The vehicle was a rental, and no one knew how to open the tank. Five highly educated theatre artists in a rural Alabama service station were trying to spring open a gas cap. It was a situation as contradictory as the reality of what these artists were investigating: the “State of the South.” After several minutes skimming the manual and trying to find the button, the gas tank was opened with a mere plunge-and-pull of the finger into the hatch’s lilted crevice. The tank got filled, the trek continued—another town was awaiting their arrival.

For a theatre of Alabama Shakespeare Festival’s size—with a campus, built in 1985, modeled after the English countryside, with a castle-like panorama complete with rolling hills, a Thomas Kinkade lagoon, and a roof nippled with festival flags—the irony of this peripatetic initiative’s premise is notable. After all, this red-brick theatre in Montgomery was built as a destination for families to road-trip to. Now the building is the van’s departing port. The destinations are the towns. The grand old theatre is going grassroots.

The road trip is a vision from artistic director Rick Dildine’s Americana palette. Dildine, the Arkansan former a.d. of Shakespeare Festival St. Louis, has an affinity for relationship-building. Dildine believes that people teach the institution, not the other way around. This mindset was the premise behind Shakespeare in the Streets—an annual season slot where a Shakespearean play is adapted in the zeitgeist of a St. Louis neighborhood and performed in the community outside, free of charge. For Dildine, now in his second season at ASF, institutional structures require sculpting in the same spirit of creative alchemy as directing a play.

The current initiative had its seeds when Dildine happened to notice something odd about the mission statement of the theatre’s flagship new-play initiative, the Southern Writers’ Project. Composed in 1991, it read, “The Southern Writers’ Project has featured both acclaimed Southern and African American writers”—as if “African American” was somehow distinct from “Southern.”

“I think it’s automatically coded white,” says Atlanta playwright Addae Moon of the lore of the Southern writer. “Normally, when people frame the idea [of a Southern writer], they don’t think of people who look like me….I had to claim that identity for myself. I’m an American writer, I’m a black writer, I’m a Southern writer. All at the same time.”

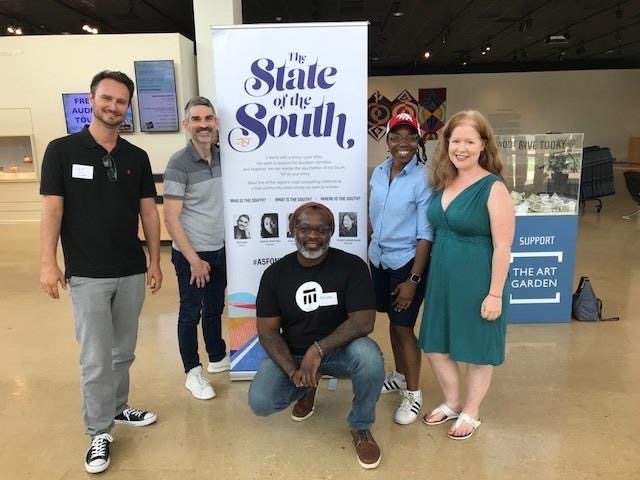

Moon was one of the four playwrights in the van, along with South Carolinians Donnetta Lavinia Grays and David Lee Nelson (who got his MFA at Alabama Shakes), and Elyzabeth Wilder, an Alabamian who has a long production history with the ASF and the Writers’ Project. It was a team balanced with the precision of conscious casting: a representative mix between black and white, male and female, gay and straight, ASF vets and new faces. The common denominators were that all playwrights see themselves within the Southern identity and all have innovative writing styles. There was not a jot of Foote, Henley, or Williams aboard.

“The tour was meant to stoke our imagination about what it means to be Southern,” says Dildine. “The time is ripe for a new Southern canon.”

The team was to visit 12 locations from Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Georgia, both big cities and tiny towns. With each artist captaining a stop, they collaborated with hosting venues like local theatres, art museums, and chamber centers to entice people out. Their charge? To research and rethink the mission of the Southern Writers’ Project to reflect the realities of the South in 2018. For many Southern communities, today’s reality is one of overwhelming contradiction, filled with beauty and oh so much pain, pressurized through the generations.

“I’m very interested in this push-pull of heartache and celebration inside of what it means to be a Southerner,” says Grays.

The South’s contradictory nature was on full display at the first stop of the tour: Montgomery, the theatre’s hometown. But the State of the South road trip didn’t launch at the State Theatre’s palatial venue but 8 miles away, on Dexter Avenue.

At the top of Dexter Avenue, in front of the plantation-white State Capitol, is a defiant and haunting statue of the racist Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, gazing down the avenue where his inauguration parade once marched. Another march took place on Dexter: the March from Selma by Civil Rights activists. Directly across the dome of the Capitol is the humble steeple of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. changed the world from the pulpit. At the foot of the avenue is where the telegram announcing the Civil War was sent; it’s also the site where Rosa Parks boarded and defied a segregated city bus in protest, rallying the fight for human rights.

The launching pad of ASF’s first town hall as part of the project was in the revitalized Kress building on Dexter, an old segregated five-and-dime store which has been repurposed into a chic community center and office space, with a hip coffee shop named “Prevail Union.” Roughly 60 people showed. The town hall started with Dildine, along with community partners from the podcast Foreword South, popping out some igniting questions: “What do you like about the South? What would you change about the South?” From there, smaller groups were divided up, with playwrights leading roundtable discussions that cued more specific questions, like “Who are your people?” and “How do you claim ownership?”

If the town hall format evokes the political—well, that’s because it is. A multi-state listening circuit can look more like a political campaign than like traditional dramaturgical research.

“I don’t think theatre alone changes society,” says Dildine. “I think theatre changes people, and people change society when they vote. The key parts to the work of an artist are listening to the community and responding with a creative act. Within five hours of ASF are 26 million people. As a destination theatre, our identity and programming will be tied to the region.”

In Montgomery it became clear that Southerners feel as restless about their region as the most cynical outsider. Though many love the natural beauty of the South, the trees in particular, there is also the memory of how those Southern trees were used: as tools of white terroristic violence, when innocent African Americans were hanged in demented mob spectacles. Today’s generations of Southerners are not too far removed from this history.

Many spoke about how they love “Southern hospitality” and “porch talk,” but also how that homey rhetoric can be “weaponized to mask true feelings,” as Wilder put it. “‘Bless your heart’ can cut you like a knife,” says Dildine.

A few participants repeated the old saw that the most segregated hour in the South is 10 in the morning on Sundays, when folks go to church. While the African American Baptist church has often been a harbor and sanctuary for human dignity, American music, and Civil Rights action, the white Southern Baptist Church often acts more as a conservative voting bloc, with conveniently indignant hypocrisy and strategic silence.

In Montgomery participants wrestled with both pride and their humiliation. “The image that’s painted of the South, the Heart of Dixie, is a shameful one,” says Emerald Kelleher, a proudly identifying trans woman who attended the Montgomery town hall. “Events like these—artistic movements—can change that reality.”

“It’s liberating,” says Tabitha Isner, a Democratic congressional candidate in one of the few swing districts in the Deep South who also attended. “People are hungry and thirsty for being liberated from the traditional narrative about the South. It’s so important we gather these stories together and fight against the stereotypes of the South. I’m excited about creating new work from the Southern identity.”

There is a progressive Southern attitude of, if we don’t fix it, who will? “What popped up in every town we went to was this love of place,” says Nelson. “No matter what the challenges were, there was something instinctual or inherent, it seemed, about these people’s love for the land from which they come. A lot of our nation’s problems were started here, and a lot of them can be fixed here.”

Attempting to understand the Southern knot through grassroots theatre is nothing new. When Gilbert Moses co-founded the Free Southern Theater in 1963, he wrote to his collaborators, “That it [the South] has existed and continues to exist with so many inherent contradictions is incredible—and oddly, an indication of man’s indomitability, but by no means a credit to the human race and its intelligence.”

Coordinating playwrights in collective movement and public engagement has been championed for decades by many activist-minded Southern-born theatre artists. Alternate Roots, an arts and advocacy organization, has long pondered the role of the Southern writer, publishing its first anthology of socially charged plays two years after the Southern Writers’ Project was started.

But ASF, a multi-million-dollar-budgeted theatre, has a notable power of privilege. “Rick is saying is that we have this responsibility because of our visibility,” says Grays. “There are a lot of commonalities [in the South], but it’s interesting to see where stories diverge—and to see who’s not being represented in Southern stories.”

Says Moon, “There are so many stories that exist outside of the whole ‘moonlight and magnolias’ thing that really need to be told and can change people’s perception about what the South is. I think the American theatre has the exact same problem…I mean, we have a theatrical canon that is still problematic as fuck. In the same way that people paint the ‘Southern’ experience as white, the ‘American’ narrative is very similar.”

All the playwrights acknowledged a radical honesty when Southerners gathered to talk about issues of race—a coarse up-frontness that was waiting to burst out. “We know we’re fucked up,” exclaimed one white participant at the town hall in Mobile, “but at least we own it.”

If the town halls felt heavy, the artists could always look forward to the drive after. Dildine insisted they use the commuting time to unpack what they heard from the communities. The minivan became a four-wheeled writers’ room; though the car was moving fast, the reflections were slow, deliberate, and deep. Also in the van, they had fun and laughed—a lot. “I think I laughed more in the 10 days in that van than I’ve laughed in the past 10 months,” says Wilder.

“We didn’t really hit our stride until we hit Jackson,” she says. “That’s when we figured out what worked.” In Jackson, Miss., their fourth stop, a critical modification was made—no more breakout sessions, only one big circle. “So people could look each other in the eyes,” says Dildine. The change was a revelation. Participants were no longer able to curate which breakout session they wanted to attend (i.e., the crowd they felt most comfortable with); now they had to all face each other in fellowship. “We had moments where we could see people in the community really talking to each other and people really hearing things for the first time,” says Wilder. “You know what I mean?”

Though the formal purpose of the touring investigation was to inspire renovations to the mission of the Southern Writers’ Project, one must wonder—with four playwrights now having gulped down the South’s unique cocktail—does the new Southern canon begin with Moon, Grays, Wilder, and Nelson? The next step now is for the playwrights to compose a written response reflecting their observations on the State of the South and their thoughts about the next stage for the new-play development program at ASF.

“From the moment I had the idea to go on the road and interview people about what it means to be Southern, I have never once tried to predict what will happen,” says Dildine. “The community will tell you what the next step is.”

Indeed they will. Paul Lockett, an 18-year-old African American student, lingered after the Mobile town hall to speak with 62-year-old Liz Luther, a fellow Alabamian. “The biggest thing that perpetuates the idea surrounding the South now comes from art that was made in the past,” he says. “The way to change that is through culture—saying, ‘Okay, yes, that was the past, but now let’s look forward to the future.’ Let’s tell all the stories that are happening in the South today.”

Alex Ates is a writer, director, teacher, and actor from New Orleans. He is a contributing writer for Backstage.