In 1988, playwright/director Carolyn Gage was feeling tired. At first she thought it was just because she had started a theatre company. “I did 16 shows that I wrote, directed, and produced in about two and a half years,” Gage recalled. But this was not the kind of tired that went away with a good night’s sleep. It was a recurring “extreme fatigue” that didn’t abate, no matter how much time off she took or how much she slept. Her symptoms became so debilitating that she hardly left her room for a year.

“At this time I didn’t have a diagnosis—I was calling it a nervous breakdown,” she said.

The unrelenting exhaustion Gage experienced would later be diagnosed as myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome, which according to the Mayo Clinic is characterized by fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, and “extreme exhaustion lasting more than 24 hours after physical or mental exercise.”

Gage’s experience navigating the theatre industry with an undisclosed disability or chronic illness is not rare, just rarely talked about. A recent diversity study by Actors Equity Association, which surveyed 50,920 members, recorded that only 219 members, or .0043 percent, self-identify as having a disability. It’s a number the union acknowledges is not representative of the actual disabled population.

Presumably some Equity members are not reporting their disability; as Equity itself notes, “We are aware that many members choose not to self-identify [as disabled] for any number of reasons.” It’s probably safe to assume that some of these numbers are “hidden” because their disabilities are effectively invisible.

The Invisible Disabilities Association defines invisible disability as “a physical, mental, or neurological condition that limits a person’s movements, senses, or activities that is invisible to the onlooker,” this includes conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS), diabetes, and mental illness.

Taylor Norton, artistic director of New York City’s Access Theater, was diagnosed with MS while in college. “Obviously it’s an invisible disease—no one’s ever looked at me and said, ‘Oh, you have MS, don’t you?’” said Norton. “Part of what’s tough with a disability or a chronic illness is the question of competence.”

Indeed, the fear that others will make assumptions about one’s capacity to execute the job means there’s still a harsh stigma about disabilities within the theatre community, which can motivate theatremakers with invisible disabilities to keep their conditions secret out of concern for negative career repercussions.

To combat these misconceptions, many theatremakers feel the need to overcompensate for their perceived limitations by flaunting their special skills or their extraordinary productivity, all to simply be considered equally alongside non-disabled artists in the eyes of employers and casting directors.

But Norton views this mindset as reductive, having always maintained a personal policy of openness around her condition while in the rehearsal room. “The energy of having to prove yourself is ultimately harmful to you and your body and your stress level,” she remarked. “Be honest, because you don’t want to be in a room where you’re not wanted.”

Alethea Bakogeorge, a BFA student studying musical theatre (she declined to state where), has grappled with discrimination based on revealing her disability firsthand. When researching musical theatre programs, Bakogeorge searched for schools that did not require a dance audition.

“Since I have cerebral palsy and it affects my right leg, I’m not going to be the best dancer,” said Bakogeorge. “I kind of have the privilege to pass as non-disabled in certain scenarios, so I can kind of figure out when I wanted to disclose.” She admitted that when she was 17 years old and auditioning for training programs, her “biggest fear was that somebody would notice my disability and that they wouldn’t admit me into the program.”

Bakogeorge believes that choosing not to disclose helped her get acceptance into a university program. But since she recently became more open about her cerebral palsy, she noticed that she’s received fewer musical theatre opportunities at her school, especially in comparison to her non-disabled classmates. Now nearly finished with her degree, Bakogeorge has yet to be cast in a musical at her institution, which she admitted has been “disheartening.”

Despite being passed over by her university, Bakogeorge was cast in the national tour of Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, a live musical based on a popular PBS children’s show. Bakogeorge played the role of Chrissy, a character with an undefined disability who uses leg braces like the ones Bakogeorge used growing up.

Touring with Daniel Tiger has offered her the perfect opportunity to gain performance experience while promoting inclusive representation of disabilities onstage, and Bakogeorge said she wishes theatre training programs would embrace a similarly inclusive mindset when it comes to training the next generation of performers.

“One of the things I love most about our profession is that it’s creative problem-solving in action,” she said. “Everything about theatre is about finding different ways to show concepts that we are all familiar with to an audience, so I think if we really just apply more of that creative problem-solving to the pedagogical classroom experience, more people would have an easier time getting through their degrees.”

For others, the answer to navigating an undisclosed disability while working in theatre is to exit the stage. Former Twin Cities actress Kate Eifrig had to walk away from her acting career to better treat her depression. Now, as an anti-stigma speaker for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, she is working to dismantle the stereotypes which discourage people from seeking treatment.

According to Eifrig, if anything mental illness is too normalized, even romanticized, in the theatre, by which she means “the idea that, ‘Oh, they’re a crazy artist’ or, ‘They’re creative, so they’re scatterbrained’ or ‘moody’ or ‘irrational.’” Eifrig conceded that she is still “grieving theatre,” but that she personally could not see a way to continue in the industry while maintaining her mental health. As Eifrig’s condition escalated from an illness to a disability, she found that theatre became an unhealthy coping mechanism for ignoring her symptoms.

“It’s a double-edged sword, because, as performers, a lot of people are always ‘on’ in their community,” said Eifrig. “And if you’re trying to deal with your illness and you don’t want to feel it, you don’t want to deal with it, a lot of people joke around that theatre is therapy or theatre is a way to cope, which to me is dangerous.”

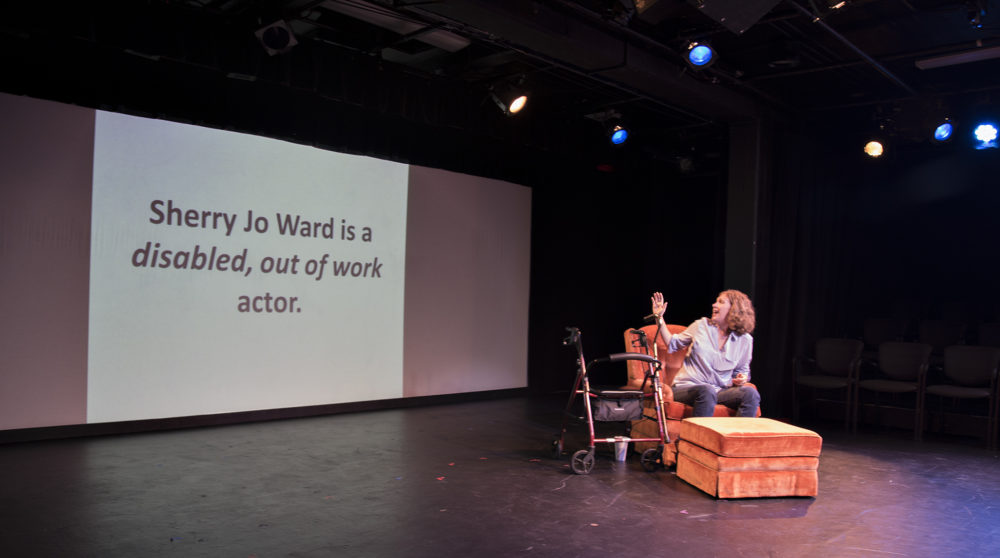

Whereas Eifrig’s work ending stigma has required her to exit the stage, actor Sherry-Jo Ward has found her calling by taking to the stage to promote awareness. For Ward, what started as invisible and seemingly minor symptoms quickly grew into a serious and visibly disabling condition. Two years ago, she explained, she “started having kind of odd symptoms: numbness and pain and fatigue, that kind of thing. And then just suddenly I started having tremors and falling.”

Neurologist’s tests confirmed a very serious cause for these symptoms: She had stiff-person syndrome (SPS), a rare neuromuscular disease which causes fluctuating muscle rigidity.

“Within just a couple of weeks I lost my mobility,” she recounted, and experienced “muscle spasms and pain, which made not only participating in theatre hard but also going to theatre.” Not only did Ward suddenly feel unwelcome in her own body; not being able to work made her feel “like I was taken out of the community.”

A role that was able to accommodate the progressive nature of her condition did not exist, so Ward wrote her own. The resulting play, STIFF, is not an inspirational narrative of overcoming adversity but a raw comedic glimpse into adjusting to life with a rare disability.

She was surprised to hear that her experiences navigating her visible disability also resonated deeply with audience members who have invisible disabilities, such as Crohn’s disease. “I’ve had people coming up to me saying, ‘I get this, I understand this, I haven’t been able to explain this, and this explains what I’m going through,’” said Ward.

Until more theatres and training programs are enthusiastically willing to take a cue from disabled theatremakers when it comes to inclusivity and accommodations, the list of reasons not to self-identify with a disability and seek accommodations won’t become any shorter.

If Ward has anything to say about it, the struggles faced by herself and many of her audience members won’t remain out of sight for long. So far she has performed Stiff around the country, in theatres in Minneapolis and Fort Worth, Texas, as well as medical schools and facilities; the show will next tour to Montgomery, Ala. “It’s become sort of my life’s work, my mission work, to get it out there and to get it seen by as many people as possible,” said Ward.

Christie Honore is a recent graduate of Vassar College with a major in drama and a minor in English. She is currently a freelance writer and publishing assistant based in Honolulu, HI.