“We are a long way from Tea and Sympathy here,” critic Clive Barnes wrote in The New York Times the morning after The Boys in the Band began its landmark 1,001-performance run at Theatre Four on West 55th Street. “The point is that this is not a play about a homosexual, but a play that takes the homosexual milieu, and the homosexual way of life, totally for granted and uses this as a valid basis of human experience. Thus it is a homosexual play, not a play about homosexuality.”

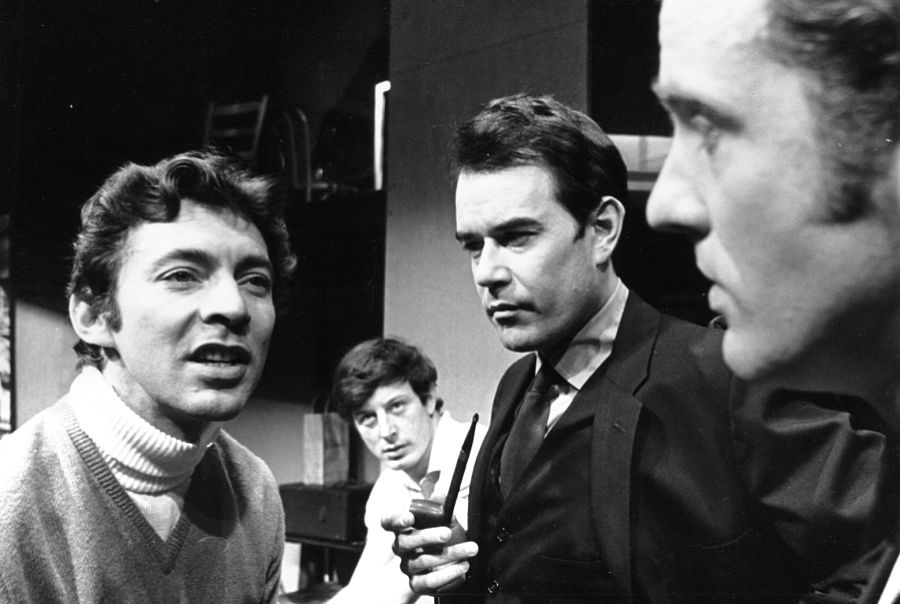

Indeed Mart Crowley’s 1968 classic about a birthday party fueled by booze and bitchiness was the first to raise the mainstream theatre curtain on a previously shuttered gay culture, and being first is never easy. Crowley could tell from the dust stirred up by actors stampeding in the opposite direction. In those homophobic Dark Ages, any gay role was considered career suicide, and The Boys in the Band required a sacrifice of nine.

Ironically the first boy to join this band—Laurence Luckinbill, now 83—was, and is, straight. And he’s now lived to see the play take its proper place on Broadway at the Booth half a century later, proudly boasting, in a sign of the times, a “100 percent openly gay cast.”

Though they didn’t share a sexual orientation, Crowley and Luckinbill had many other things in common, including the same agent—a lesbian married to a gay man. Even she suggested that Luckinbill pass on the play. But the actor wouldn’t listen. He liked the play and knew instinctively that it would have a helluva social impact on the times. What’s more, he liked the playwright. “I have known Mart Crowley for over 60 years,” he told me recently. “We met in college. I was a graduate student, and he was an undergraduate, at Catholic U in Washington, D.C.”

Another common touchstone: their mutually gnarled Southern roots.

“I am from Arkansas, and he is from Mississippi,” said Luckinbill. “That has been a lifelong connection between us that a lot of people in the North don’t understand. It’s just that we know how things are, so we understand each other in a different way. I always had a close feeling about him.”

Crowley often visited Luckinbill in Fort Smith, Ark., and their friendship deepened. “We’d hang out for two or three days and do all the things that you did in my home town—basically, go to the Dairy Queen. It was summertime, and we talked a lot about our families, because we both came from substance-abusing homes. There was a lot of that stuff going on then. When you’re young, it’s a major deal, but when you’re old, you begin to see a lot wider scope of things—how it really was with your parents.”

These days Luckinbill is in the throes of writing a memoir, which he is calling modestly (but quite correctly) Famous Enough. So he’s been conjuring up lots of memories of The Boys in the Band, which wound up consuming three years of his life and a vast variety of venues, from a workshop to an Off-Broadway run to an original cast recording (“Boy! did we get stiffed by Herb Alpert’s company! They paid us pittance, but we’re actors—what are we going to do?”) to a London run to a film that reunited the original nine.

“When I entered upon this, it was purely as Mart’s friend,” he said. “He gave me the script, I read it overnight, and we met the next day at Jack LaLanne’s in Sheridan Square, on the street, in the freezing cold. He had the play cradled to his breast like a baby. It was the story of his life, and some people were actually repelled by it. That’s a pretty hard thing to take when you’re going around with your baby trying to sell it. He told me that he had even had a very hard time just getting anyone to read it.

“I said yes to doing the play immediately because of our friendship. He nearly cried. He didn’t, because that’s Mart—a really tough guy. I didn’t care what our agent said. I didn’t even care what my wife said. That was Robin Strasser at the time—but she was very supportive, because she’s an actress and she understood. I didn’t care what happened to me, because I felt I was strong enough in my own career to weather it.”

Having made his Broadway debut in 1961’s A Man for All Seasons with Paul Scofield, Luckinbill returned in Beekman Place and Tartuffe while simultaneously amassing a nice soap opera following via “The Secret Storm” and “Where the Heart Is.”

After agreeing to do the play, there was the awkward business of deciding which part to do. Luckinbill first had his eye on the meaty lead role of Michael, the mean-drunk host from hell who puts his guests through very cruel hoops and loops. Crowley nixed the idea. Next Luckinbill looks at “the smart-mouthed guy, Larry,” who gets a stolid schoolteacher to leave his wife but still keeps up his philandering (“gypsy feet,” one character calls it). Again, no. What Crowley had in mind was Hank, the guy Larry is cuckolding. Luckinbill was less than thrilled.

“My first thought was, ‘Hank’s the square guy, he’s got to be dull,’ but I’d already said yes. Actually I’d have done it, no matter what—and I’m so glad I did. That role was a godsend. Over these 50 years, numerous men have come up and thanked me for Hank. One guy said, ‘I saw the play as a teenager and thought Hank such a strong character, I went home and told my parents I was gay.’ That’s a big moment in men’s lives. ‘How’d they take it?’ He said, ‘They hugged me and told me they loved me.’”

That chorus has continued since he and now-wife Lucie Arnaz shifted coasts and settled in Palm Springs, where there’s a large gay population. “I hear that story twice a year here,” Luckinbill said. “One famous lyricist who lives here told me he saw the film at 17 and found in Hank someone he could identify with—someone not afraid to say what he was.”

Hank is something of a cerebral center at this calamitous clambake, a hunk of quiet authority puffing away pensively on a pipe like an island unto himself, assessing the collateral damage around him. The pipe was the prop Luckinbill brought to the part. “That’s what I smoked then. I never ever smoked a cigarette. I hated ’em, but I smoked a pipe because my grandfather smoked a pipe and I wanted to be like him. Now, of course, I wish that I hadn’t even smoked a pipe, because I have emphysema.”

Audiences who came to observe the intimacy onstage never knew that they were also being scoped by the cast from offstage, thanks to some skills Luckinbill picked up at college. “At Catholic University, I was a carpenter for my tuition, so I had a bag of tools when I came to New York. and could farm myself out as a handyman to make a living during those early years.” So when Boys got to the Off-Broadway stage after its workshop, he dragged out his toolkit and applied it to the back of Peter Harvey’s set (which consisted of black-and-white photographs taken at Bloomingdale’s Men’s Department), burrowing a peep-hole in it so actors about to go on could ogle the parade of celebs occupying the prime seats. There were plenty: Jackie O, Mayor Lindsay, Nureyev, Marlene, Groucho, and so on.

One audience also included a couple of conservative Catholic Southerners, Mr. and Mrs. Luckinbill of Fort Smith, Ark.

“I’m watching right through the hole when my parents hear the line, ‘Who do you have to fuck to get a drink around here?’ My father’s mouth tightened, and my mother kinda put her gloved hand to her mouth. It wasn’t in horror. It was funny. They were in shock, but it was a kind of ‘Oh, my goodness!’ type of shock.”

The original nine Boys in the Band stuck together like Krazy Glue for every run that came up during its first three years—a rarity in the business. But even that distinction has a tiny asterisk: “One person really hated his part—I believe he was playing Michael—and he created such a mess the day we started rehearsing for our workshop that Robert Moore, the director, replaced him. I recall the guy vividly, what he looks like—he had a bit of a career—but I’m not going to name him.”

Cliff Gorman, who minced memorably as the extravagantly effete Emory, had no idea that what he was doing was funny until the first workshop performance at a tiny little closet of a theatre called the Vandam; initially, the audience uproar made Gorman think the scenery was falling down behind him. “We were all in total shock,” Luckinbill remembered. “We knew it was funny, but we didn’t know it was a laugh riot. We didn’t know we’d be interrupted constantly by the audience. We stumbled through on each other’s laugh lines—Bob Moore came backstage that first performance and said, ‘Bumpy!’ But we ironed it out finally, and by the time we got to Theatre Four, we knew what we had, I think.”

The workshop was scheduled for only five performances, but the morning after the first one, Luckinbill came out of his Sullivan Street apartment and saw a huge crowd of men standing in the street, forming a line that extended from Sixth Avenue across Houston Street and into the Village. “It was astounding. Every one of them was gay. Overnight, the word had gone out that there was something happening downtown that represented them. The closet door flung open, and those men stood there.”

The 1970 movie version, directed by William Friedkin (fresh from his Oscar win for The French Connection) and produced by Dominick Dunne (for a measly $1.25 million), is a classic example of how film can properly preserve a stage play. Having the original cast on hand emphatically helped—and that only happened because Crowley dug in his heels. Hollywood producer Ray Stark threw stars and cash at him, proposing the likes of Rock Hudson, Tab Hunter, Roddy McDowall, et al., but the playwright wouldn’t hear of it.

HIV/AIDS, which lurked around the corner from the Stonewall riots a dozen or so years later, would decimate the original company, starting with director Moore, 57, in 1984, and ending with the original Michael, Kenneth Nelson, 63 (who had begun as the original Boy in The Fantasticks). In the interim the plague claimed a majority of the cast. First in 1984 was Robert La Tourneaux, 45, the $20-hustler “birthday present” who was gift-wrapped as a cowboy for the haughty honoree, Harold. The birthday boy himself (Leonard Frey, 49) followed next, in 1988. Producer Richard Barr died at 71 in 1989, and two of the party guests—Donald (Frederick Combs, 57) and Larry (Keith Prentice, 52)—died just eight days apart in September 1992.

Gorman, who won an Obie for playing Emory and subsequently a Tony for his work in Lenny, succumbed to leukemia at 65 in 2002. He and his wife had taken care of the dying La Tourneaux.

By last spring, when the 50th anniversary Broadway revival rolled out, only three of the original cast were left standing. Two attended the opening: Luckinbill, with Arnaz, and Peter White, 81, Michael’s presumably straight college roommate who stumbles into this hornet’s nest of homos. The third—Reuben Greene, 79, who was the lone African-American in the Band, Bernard—no longer discusses the film or associates with his castmates.

In contrast, Luckinbill drumbeats like a one-man band about the show. When he talks of the revival, he’s almost evangelical: “I thought it was splendid. Joe Mantello is a genius. Not only is he the best director working now, he’s the most tasteful.” Indeed, Luckinbill said his déjà vu was minimal “because the show is so Joe now.” Incidentally, Mantello also has a home in Palm Springs, and huddled extensively with Luckinbill about the Boys’ reboot.

“If anything, each of the characters is now sharper,” said Luckinbill. “They’re more fully invested in their angers and in their particular ways of getting through life. Back in 1968, the closet was fully shut. I think guys like Leonard and Kenneth and so on who decided to do this took much more of a chance than the two of us who were straight.”

It was worth the risk, though. “This was the first time I realized there was such a thing as social justice being enacted in the theatre,” Luckinbill marveled. “It was the start of a revolution. Boys in the Band turned the ignition of the gay liberation movement, and Stonewall came the following year.” For Luckinbill, it taught him that “my career only matters to me if I can do something to further society, to make it better.”