The cast of The Iceman Cometh stands in a circle onstage at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, hands clasped, lines from the play ricocheting from one actor to another. It’s a starry group—David Morse, Bill Irwin, Colm Meaney, and, of course, Denzel Washington—yet during this rehearsal they are left in semi-darkness. The only person fully illuminated is an 80-year-old man, standing alone, unmoving, at the top of the staircase stage right.

That man, Jules Fisher, is not part of the cast, yet he is an essential part of the show; he has been lighting up stages in New York City (and beyond) for more than 50 years. Fisher, along with his working partner Peggy Eisenhauer, 55, are among the preeminent lighting designers in the American theatre, while also lending their illuminative talents to movies, rock concerts, opera, and Las Vegas spectacles. Fisher made his Broadway debut in 1963, seven years before a Tony Award for lighting even existed. He has been nominated, solo or with Eisenhauer, 21 times for that award, winning nine.

Light is, of course, ephemeral—both wave and particle, a thing and not a thing. And even for old hands like Fisher and Eisenhauer, things get a bit blurry when they try to describe what they do, whether it’s to a reporter or to a director counting on them to match his or her vision, or to a producer about to lay out a major investment for the equipment they need before a show.

“Our primary job is enhancing the mood and emotion of the storytelling,” Eisenhauer says, hastening to add, “The most difficult thing about being a lighting designer is communicating what we do.”

The pair has struggled over the years to develop a vocabulary that directors and producers can relate to, pulling in words or phrases from other media. “We can relate something we’re planning to a painting or music or to a scene from The Godfather,” Fisher says, and Eisenhauer chimes in that they “collect words” that resonate—“words about speed and tempo and time, or an emotional quality, and every word that has to do with brightness or dimness or darkness or shadow and time of day.”

Ultimately, Fisher says, to communicate fully they need to look at the director face to face to “see in their eyes if they understand what we are saying. We are trying to inhabit the mind of the director.”

This kind of mind reading is necessary because, until a show is up onstage, there is no way to demonstrate in advance how a lighting design will work. Even during that Iceman rehearsal, Fisher was pointing out how the actors’ street clothes would reflect or absorb the light differently than their costumes.

“We can’t show them what we are planning beforehand,” Fisher emphasizes. “The costume designers or scenic designers can bring a rendering, a photograph, or a model to show the director or producer.” This isn’t just an aesthetic challenge but an economic one: Producers have to take their word that they need a half-million dollars worth of equipment rather than a quarter-million dollars worth. “It is a gigantic leap of faith on the part of producers,” Eisenhauer concedes, explaining that directors are at least more attuned to their ideas and concepts, like working with the dynamics of a space.

Some of this has to be modesty, as directors continually clamor to work with the duo. Director George C. Wolfe has previously collaborated with them 11 times before Iceman. “George shows confidence in us, and we’ve developed a shorthand with him,” Fisher says. “He rarely says ‘make this blue’ or ‘make that brighter’—he’ll say, ‘I don’t understand the fear in that scene,’” and his designers will interpret that on their lighting board.

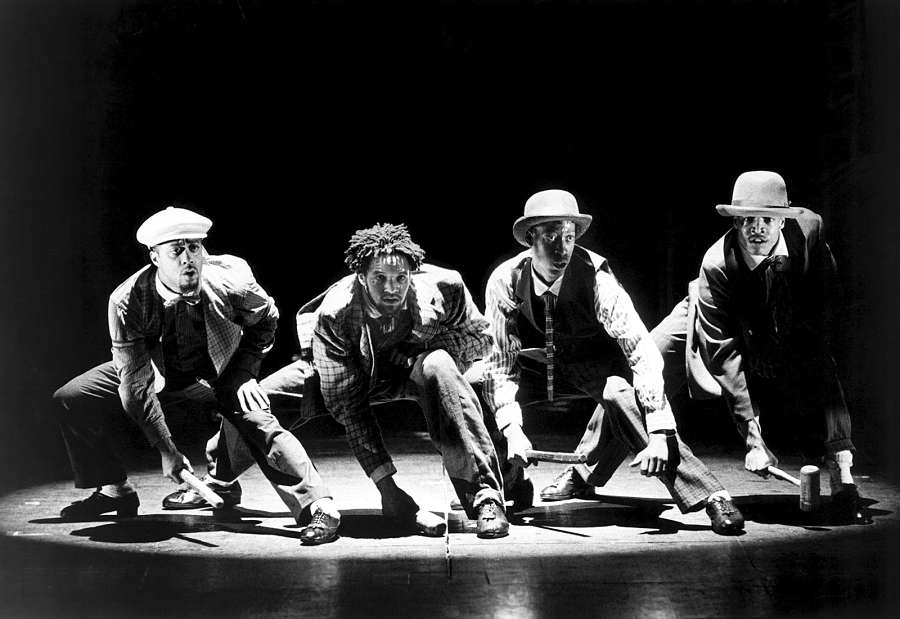

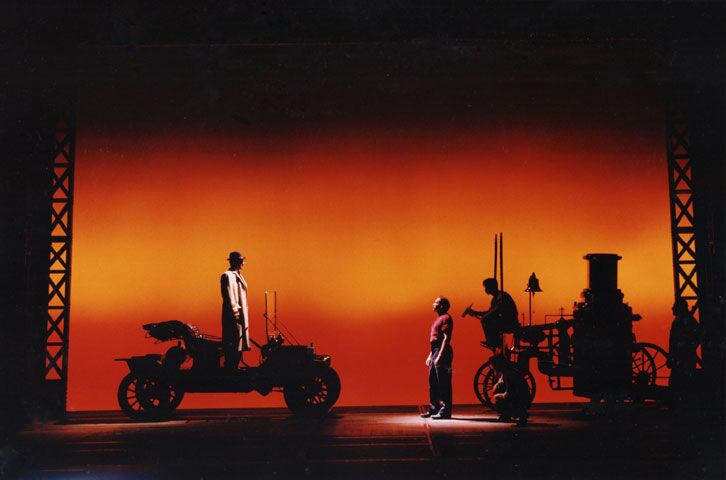

Wolfe might be the team’s biggest fan. “They have incredible sense of craft and storytelling, regardless of what show it is,” the prolific director says. “On Jelly’s Last Jam, I had the idea of darkness as a color, and they were able to articulate that. And on Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk, I wanted lighting fueled by the rhythm—and they did that.”

In Noise/Funk, Wolfe wanted the dancing to suddenly bring a lynching to mind. He says that Eisenhauer and Fisher took that impulse and translated it by embedding a light in the cotton bales onstage to make it look like the dancer’s head was disembodied.

Fisher had climbed up onstage during Wolfe’s Iceman rehearsal just hours before a preview because he and Eisenhauer were relentlessly trying to tweak a minor problem. “Denzel leans over every night when he’s on the staircase, taking him out where there is no light,” Fisher explains, after climbing down from Washington’s spot on the staircase. “We ask him to stand straight, but he has his way of doing it. Now Peggy has found way to keep him in the light that should work. We’ll see tonight.”

The Lennon-McCartney-style share-all-credit partnership between Fisher and Eisenhauer is unusual in lighting design, which is typically a field for solo artists, and it’s even more surprising because of the quarter-century difference in their ages. Yet it was that gap that actually led to their working together.

Fisher grew up in Norristown, Pa., and as a child aspired to be a magician, another field that relies on a flair for making audiences see what you want them to see. An uncle in New York would take him to magic shows where he’d see how the magicians used lighting to their advantage. In Delbert Unruh’s book The Designs of Jules Fisher, the designer recalls building a puppet theatre with red and blue bulbs, then creating switches that enabled him to mix the colors in different ways. On the stage crew in high school, he’d sneak in alone and run the dimmers in the theatre to see how the colors mixed there.

“I liked science—the idea of the physics of things,” Fisher recalls. He really wanted to be a magician, but this son of a delicatessen owner was “too practical” to take the plunge. “Maybe it was a mistake—maybe I would have been a wonderful magician,” he says with a laugh.

Instead, in 1954, after his last year of high school, he worked for the summer at the Valley Forge Music Fair doing various jobs. “I looked up at the lighting and said, ‘I can do that,’” Fisher recalls. He got encouragement from a colleague who told him that Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon) had the top lighting program. Fisher was already enrolled at Penn State but he quit to move to Philadelphia, where he picked up a job loading in shows, many heading for Broadway, while working in lighting in amateur theatre.

One day he was carrying lights for The Most Happy Fella when designing legend Jo Mielziner took the time to explain some tricks of the trade to him. That made a lasting impression and helped inspire Fisher to apply to Carnegie Tech to study lighting. During his senior year there, a friend who had graduated invited him to light All the King’s Men Off-Broadway, so he got permission to miss a couple of weeks of class. Then that show’s scenic designer invited him to light the Off-Broadway production of Jerry Herman’s Parade. His professors weren’t thrilled, but Fisher would not be deterred—even when that gig led to a third show and more missed class time. He did finally graduate, and was able to move to New York as an established lighting designer in 1960.

Fisher worked on nearly two dozen Off-Broadway shows—and patented one of the first pan-and-tilt moving lights—before landing his first Broadway job in 1963 in Spoon River Anthology. He got to work with everyone from Mielziner to Richard Rodgers to Stephen Sondheim, and lit Hair not only on Broadway but all over the world. By the 1970s, he’d emerged as a star. In one seven-year span, he lit 21 Broadway shows (including an Iceman starring James Earl Jones), raking in six Tony nominations and three awards.

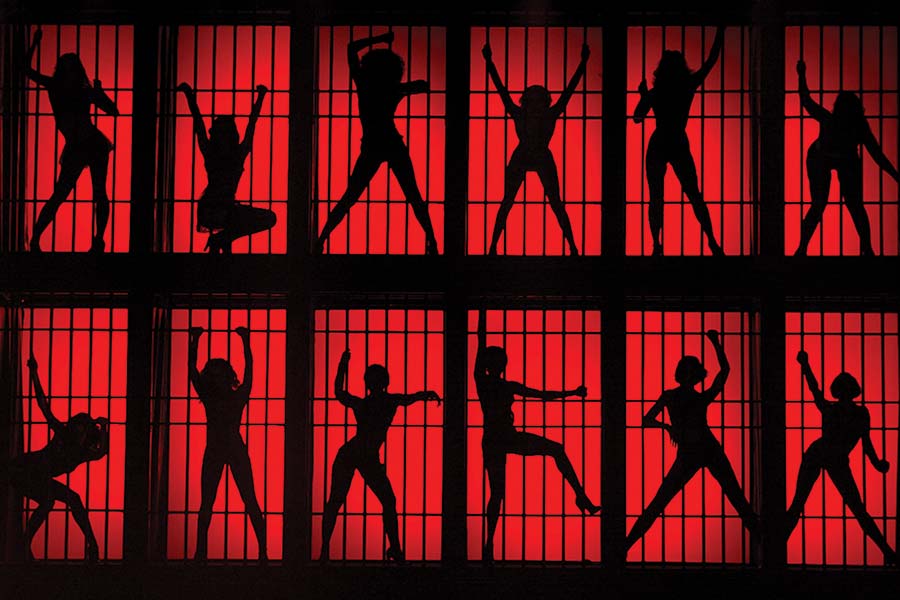

But his career also expanded wildly to include lighting and production supervision for epic tours by David Bowie, the Rolling Stones, George Clinton, and KISS, and later the Simon & Garfunkel reunion in Central Park. He oversaw the concert sequences for the Barbra Streisand movie A Star Is Born, and started theatre consulting and architectural lighting firms, with projects including the disco Studio 54. He was so much the epitome of a lighting designer that when he wasn’t lighting such Bob Fosse shows as Pippin, Chicago, and Dancin’, he was playing a lighting designer named Jules Fisher in a small role in Fosse’s film All That Jazz.

Fisher divides most directors into nurturers or despots, but says Fosse was both—he could be cruel but still get the best out of people. “I once told him my solution to a problem he’d raised, and he asked if I was sure it would work,” Fisher recalls. When Fisher expressed confidence, Fosse changed tactics, asking if Fisher had ever used that particular idea before. Fisher said he had once, but this didn’t placate the director. “He said, ‘Then I don’t want it!’ He always wanted something fresh, something new.”

Working with Fosse on Pippin brought Fisher his first Tony, but the bigger impact on his career was the effect his magical work in that show had on the audience—or at least on one teenage girl.

Peggy Eisenhauer started training in classical piano at age six in Nyack, a New York suburb. “It was very serious,” she says, explaining that the following year her instructor added music theory to her education. “My folks didn’t know where it would lead, but they felt it really was important to learn a discipline early, to learn the importance of practice.” Eisenhauer says that her relentless work ethic and willingness to try every possibility in lighting a scene to get it right dates back to those days of endless practice. “We are performing as lighting designers—we are delivering a creative performance in the now, driven by the clock of the tight production schedule.”

When Eisenhauer was 13, her attention shifted: She started hanging around a community theatre and helping out. “I thought I wanted to be a performer, maybe a tap dancer,” she says. One day a grown-up didn’t show and they stuck this teen girl on the lighting console. She loved the job and stuck with it. Within two years she was designing lighting for the theatre.

That 13th year proved particularly important, as Eisenhauer got invited by a friend to see Pippin. Just describing the experience seems to transport Eisenhauer back to the gushing enthusiasm of a teen.

“I don’t have a great visual memory, but I can still picture this moment where Ben Vereen popped out with his white gloves and black bowler hat,” Eisenhauer recalls. “He delivered his line in a sharp purple spotlight—POW. The light created a visceral sensation.”

She noted the name of the designer, Jules Fisher, and her parents—“my clipping service”—began to look for information about him and encourage her to see shows he designed. When The New York Times profiled Fisher (“above the fold,” she remembers), her mom had the paper waiting for Peggy on her breakfast plate.

Carnegie Mellon was the ideal college for an aspiring lighting designer, but Eisenhauer readily adds that one impetus for going there was to follow in Fisher’s footsteps. On the essay question that asked, “What person, living or dead, would you want to meet, and why?” she wrote about…well, everyone reading this article can guess.

During her sophomore year she saw an announcement posted about a “mandatory attendance” lecture from a certain famous alum. Her wish was about to come true. Fisher spoke to the whole theatre department, then made a special visit to a lighting class, since the professor, Bill Nelson, had also been his professor two decades earlier. Most students asked specific questions—about what gel Fisher might use on a light in a certain scene, or the like—but Eisenhauer went for the big picture, inquiring, “How do you know if you’re any good?” Neither recall what he answered, but they both know what happened next.

Eisenhauer raced out afterward and called home (“long distance”) to gush, “Mom, I met him, I met him. It was worth all the tuition!”

Eisenhauer’s mom sprang into action and found Fisher’s address in New York, writing him a note thanking him for taking the time to talk to the class and explaining how excited her daughter had been. Fisher, who had been so thrilled as a youngster when Mielziner took the time to encourage him, wrote back (“Of course I still have the letter,” Eisenhauer says with a grin) to offer to lend her a helping hand.

So in 1982, after college, Eisenhauer ditched her summer stock gig to come to New York, where Fisher’s street cred helped get her name on the roster at the Public Theater. She worked there as a spot operator for designer Richard Nelson on The Death of Von Richtofen as Witnessed from Earth. She proved her chops assisting Nelson over the next few years, and then began assisting Fisher when she was 23. Over the next seven years she was by his side for every show.

Then, around 1992, Fisher decided that that alignment no longer made sense. “I said, ‘Well, she’s just as good at this as I am, and she can make me look even better, so we should be partners.’” A few years later they incorporated as Third Eye Studio, which shares headquarters with Fisher’s architectural lighting design company, Fisher Marantz Stone, and with his theatrical consulting company, Fisher Dachs Associates.

Their work succeeds in part, Fisher believes, because they push each other. “We look at something and see two different problems and try solving both,” he says. But, Eisenhauer points out, when they are creating, they work as a single unit: “We don’t have any pride of ownership for our ideas.”

Tommy Tune, who directed four Broadway shows lit by the duo and who first worked with Fisher back in 1973, says, “They share the same eyes, with a sense of color and drama and place and time.” Tune adds that “they have an astonishing work ethic and they maintain an equilibrium that is highly appealing in the days before a show opens, when everything is crashing.”

One reason they are able to stay relatively calm, they both say, is that they have each other. Being a lighting designer, Eisenhauer concedes, can be “isolating,” with “fear and loneliness” built in. As a duo they can face those challenges with complementary strengths: she the meticulous planner, he the more patient crisis manager.

“I take pride in planning and always think ahead and use all our experience to think about possible outcomes,” Eisenhauer says. “But when the wheels start to fly off, I don’t have the flexibility. Jules can peel off and help solve the problem. It’s amazing to me how other designers do both things at once.”

“She’s more critical—in a good sense—and will tell me why something wasn’t okay, and she’s usually right,” Fisher says. “I’m more relaxed and more used to dealing with the other personnel.”

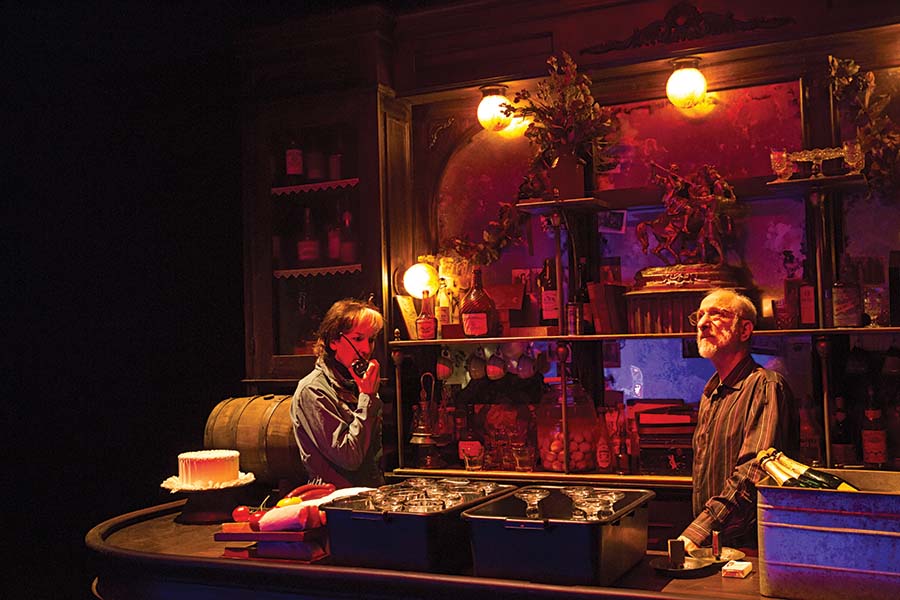

Each day during Iceman previews, Eisenhauer and Fisher made adjustments based on notes from Wolfe and from his stage manager, but the most detailed course corrections came from the pair’s own pages and pages of notes. Those early stagings are their first chance to really see how their choices play out on the actors’ varying skin tones and in their actual costumes.

“As we go on in previews, the number of notes doesn’t decline, we just get more granular in the details,” Eisenhauer said, sitting at her temporary lighting desk in the back of the orchestra one afternoon, running through various cues on her headset with her computer programmer positioned at the back of the balcony. She methodically ran through each note, taking lights up or down one at a time, discussing with Fisher his idea about changing the color correction. They would run any significant change by Wolfe, but Fisher said the director does not insist on controlling every tiny detail. “Some directors do not want us to touch anything without consulting them,” he said.

Still, no matter what the director’s style is, Eisenhauer noted, “The director’s vision always comes first and comes last. We may feel a spark of an idea and see if we can develop it on our own, but once it grows, then we submit it to the director.” The key, Fisher chimed in wryly, is to get them to own the idea. “Then they like it because they’ve said it,” he joked.

During previews, they will sit in different seats to make sure the lighting works not only from their booth but everywhere from front of the orchestra to the back of the balcony. “Sometimes the actors look great from the balcony, but you see the light causing patterns on the stage that can be a distraction,” Fisher explained. “Or you find a dark hole and you need to fix it without making it worse elsewhere.”

Iceman’s four-hour run time and large cast means lighting the show in such a way that “the audience won’t get bored,” but Wolfe insisted it not look “too pretty or eloquent,” Eisenhauer elaborated. So ultimately “what makes Iceman exciting is that we are hiding the lighting—we are pulling the audience’s attention around and setting the right mood without people really seeing it.”

By the time that show’s previews were over, they’d solved the staircase problem: When Washington briefly appeared there, he remained brilliantly lit. And then the moment was gone in the blink of an eye, before the audience could even appreciate the time and effort that had gone into perfecting it. (Tony voters at least recognized the duo’s work with their 21st nomination.)

The Fisher-Eisenhauer partnership has not changed much over the years, though Fisher says he gradually became more trusting of Eisenhauer’s superior musicality and her understanding of rhythms in lighting. And Eisenhauer says their style has evolved over time. “I like to think we carry the influences of all the directors we have worked with,” she said.

That heritage is important, she continued, pointing out that Iceman brings them back to the very venue where Eisenhauer first worked with Fisher as his assistant back in 1985.

“It’s nice feeling a sense of community and a sense of lineage,” she said. “To know that you take a little bit of George Wolfe or Bob Fosse with you—that this is where and who you come from—is just incredible.”

New York City-based arts journalist Stuart Miller writes frequently for this magazine.