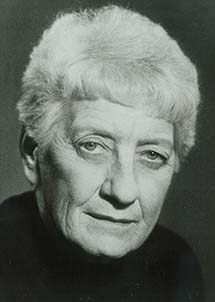

Anyone inclined to study the evolution of theatre lighting design will likely come across the Lighting Archive’s website, whose homepage features a coffee-cup ring graphic to complement this prominent quote from Tharon Musser: “A light plot is not a light plot until it has coffee stains and cigarette burns on it.”

A Tony Award winner for the landmark shows Follies, A Chorus Line, and Dreamgirls, Musser is certainly considered one of the greatest—as well as the most prolific—lighting designers ever to work on Broadway. But she was also a pioneer in lighting control technology whose work paved the way for the dazzling effects that have become synonymous with productions on the Great White Way.

Lighting designer Beverly Emmons (a multiple Tony nominee for such productions as The Elephant Man, Passion, and Jekyll & Hyde, among others) set up the Lighting Archive, as well as the Theatrical Lighting Database to provide access to hard-to-find original lighting documents.

“I chose Tharon’s quote to get people to recognize that this was all hand work,” Emmons says. “The problem with hand-drawn documents is that they look like the Dead Sea Scrolls to people nowadays.”

That may be understandable given that lighting designers, like most people in the world today, now rely on computers to do their jobs. Not only do computers run the automated lights that dominate most productions; designers also use software programs to draw and map out their light plots.

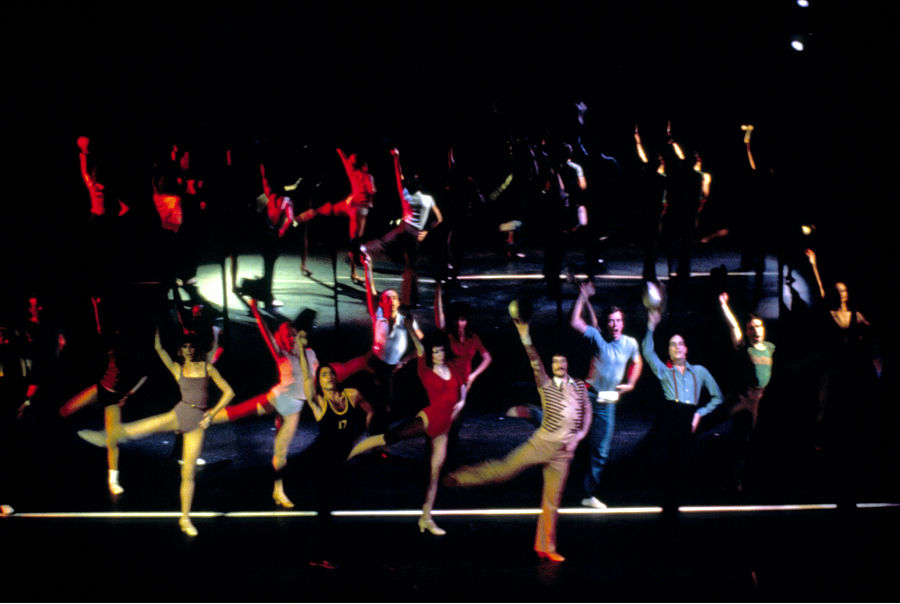

Interestingly, Musser never developed an affinity for using moving lights in her own designs, but she paved the way for their viability in theatres by introducing the LS8, a memory lighting board, on A Chorus Line in 1975. Until then every Broadway show used piano boards, which were groups of directly operated resistance dimmers that teams of electricians operated.

In his book, The Designs of Tharon Musser (published by USITT), Delbert Unruh recounts that Musser was able to convince the IATSE technicians who were opposed to using the memory board that it was necessary by running a demonstration that showed the cues she had written couldn’t be done quickly enough by hand. Though justifiably concerned about the loss of jobs, they respected Musser and were persuaded.

Widely expected to be a huge hit from its original opening at the Public Theater, A Chorus Line became a Broadway legend, with an amazing run of 6,137 performances. The show is still well remembered for Musser’s lighting, which lighting designer Natasha Katz recreated for the Broadway revival in 2006.

Tony-winning lighting designer Ken Billington (Chicago), who worked as Musser’s assistant from 1967-70, recalls that expense also played a factor in this seminal adjustment. “Tharon convinced the producers to pay for it,” he says. “The theatres then were all on direct current, not alternating current, and you can’t run automated lights on direct current.

“I put the second console on Broadway on Side by Side by Sondheim —using a console she had developed for the tours of A Chorus Line,” Billington continues. “Those two shows were the only ones on Broadway at the time that were automated, but within a year all new shows were on computerized boards. And we have not looked back since.”

A look back at Musser’s career before A Chorus Line shows that by the time she created that groundbreaking design, she had been consistently working on Broadway for almost 20 years.

Musser was born in Roanoke, Virginia in 1925, as Kathleen Welland. Orphaned at the age of two, she was adopted in 1929 by the Rev. George Musser and his wife, Hazel, who renamed her. She became interested in the theatre while in high school, though she did not enjoy performing onstage. She attended Berea College in Kentucky, and then went on to join the graduate technical design and lighting program at Yale Drama School, where she developed her interest in lighting design.

After Yale, she moved to New York and helped start up the experimental theatre Studio 7. She also began lighting dance at the 92nd Street Y, and then touring productions with choreographer Jose Limon. In 1956, she joined United Scenic Artists and earned her first Broadway credit: lighting the first U.S. production of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

The following year, 1957, Musser joined the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Conn.; she lit shows there for 13 seasons. Musser spent a lot of her time there working Jean Rosenthal, well established as one of the very first lighting designers for theatrical productions, who counted West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof among her credits.

From the end of the 1950s through the ’60s, Musser applied her creativity to the first series in what would become a very long list of notable Broadway productions. They included The Entertainer (starring Laurence Olivier), Once Upon a Mattress (starring Carol Burnett), Any Wednesday, Golden Boy, The Lion in Winter, Mame, Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, and Applause (starring Lauren Bacall).

In 1970, she created the lighting design for the groundbreaking Stephen Sondheim/James Goldman musical Follies. Directed by Harold Prince and Michael Bennett, the show won Musser her first Tony Award and a Drama Desk award.

During this decade, Musser also became playwright Neil Simon’s go-to lighting designer for his numerous Broadway plays, from The Sunshine Boys to Laughter on the 23rd Floor. Other high-profile productions followed, including A Little Night Music, Candide, and The Wiz, Same Time Next Year, Tribute (starring Jack Lemmon), and Whose Life is it Anyway?, Mark Medoff’s Children of a Lesser God, 42nd Street, Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing, and The Secret Garden.

While working on A Chorus Line, Musser became part of director Michael Bennett’s “dream team” of designers, which included set designer Robin Wagner and costume designer Theoni V. Aldredge. In 1978, they reunited to work on Ballroom, which was unsuccessful, but did inspire a young Howell Binkley (Hamilton, Jersey Boys, Come From Away), who was then just an aspiring lighting designer.

“When they were teching Ballroom at the Majestic Theatre, I just went in through the stage door and went up to the balcony to watch,” he says. “Nobody caught me, so I just stayed there. I learned so much from observing Tharon at work, which, without a question, influenced my own development as a lighting designer.

“She was always incorporating something new and innovative in her design process,” Binkley continues. “It wasn’t about having a gimmick—the technology she used always worked seamlessly in her designs. A lot of us will use something as a trick or to hide something, but her work was never about that. I have so much respect for what she brought to the theatre. I truly believe she’s the best lighting designer we have ever seen.”

The “dream team’s” follow-up to Ballroom, Dreamgirls, proved the quartet had not lost its magic. For this smash musical about the rise of a Supremes-like girl group, Musser dazzled audiences by using an upstage wall of lighting units, which garnered praise for its cinematic wipes and fades—effects that helped secure her third Tony.

Of course, Musser didn’t do it all alone, and the list of her assistants who went on to notable lighting design careers of their own is quite long. It includes Marilyn Rennagel, who became Musser’s life partner and lived with her until Musser died from Alzheimer’s disease in April 2009.

Rennagel agrees with Binkley that Musser had no patience for gimmicks. “It’s a different kind of lighting nowadays, which is sometimes painful to see—there are so many lamps on every show,” she says. “But Tharon was an economist, and she was amazing. She knew what every single lamp did and what it could do and when to use it.

“She taught me that there needs to be a thread,” Rennagel continues. “You really need to think of a concept. Then you work everything around that concept. For instance, for A Chorus Line, the colors only came in when the actors were in a memory or in their minds. Otherwise it was just plain old real light. Something will happen to the audience and lodge in their brains and the show will make more sense.”

Musser also developed box booms to give her more control over the front light. “She usually didn’t like the look of a balcony rail, because that’s really straight into the performers’ eyes,” Rennagel says. “She was looking for something a little more sculpted—and that didn’t make a line on the back wall. You could maneuver it.”

Rennagel believes that even more than her talent and skill, Musser’s professional demeanor is what keeps her legacy going strong today. “She was a tough old broad but she got along with everybody,” she says. “And she knew when to push and when not to push. She was so politically savvy in dealing with people. And at the same time she firmly believed in collaboration. She wanted everybody’s ideas out there. She genuinely loved doing what she did and it showed in her relationships with people. She was an extraordinary woman.”