Since it was posted, the following piece has inspired a lot of feedback, to put it mildly, not only in the comments section below but on social media. We decided to publish a response, which you can read here.

During a performance of Bright Star, the superb Broadway musical of two seasons past by Steve Martin and Edie Brickell, a cast member was momentarily engulfed by a cloud of fog. Stephen Bogardus, playing Daddy Cane, was “frog gigging” on the bank of a river in North Carolina, and all river banks are always completely covered in fog, as anyone who has ever been to one knows. It is a truth universally acknowledged that you cannot show a river in a play unless its banks are shrouded in fog; it just wouldn’t feel like a river. The fog gives the impression of dampness, a quality hard to convey on a dry stage—unless it’s covered with fog.

Bogardus completely disappeared for a few seconds, just like Isaac Hayes did on the Oscars that one time, earning him the nickname Isaac Haze. Eventually Stephen was able to dispel the fog with a few vigorous waves of his arms; we could see him again, and the play went on, after a few adroit improvised lines from Stephen’s voice within the cloud (“Who started the car?” and “Is the sausage burning?”).

Legends of stage fog vanishings are legion. One tale has it that after the fog cleared in Phantom of the Opera one night in the late 2000s, an actor completely disappeared, only to turn up the following week in a touring company of Jersey Boys. This is almost certainly exaggerated. (It didn’t add credibility to the tale that the allegedly apparating actor’s name was Rosco Fogg.)

Stephen Bogardus, at any rate, did not report any ill effects from his submersion. He was called on to roll over in the fog every night, breathing in quite a bit of the stuff, and so far has not reported any symptoms.

Stage “fog” is generally of two kinds: Let’s call them “fog” and “haze,” respectively. The fog that enswathed Stephen, and on which the cute angels can be seen sitting in in the current Broadway production of Carousel (sometimes it sits on them), is produced from a compound made by a German company called Look Solutions. It’s a mixture of water and triethylene glycol (a plasticizer used to make vinyl polymers, brake fluid, and air fresheners like Prestone; it’s also a disinfectant, a side benefit if an actor happens to have a sore throat). It may also contain propylene glycol, found in things like polystyrene, which is used to make styrofoam (and gives a nice kick to a mimosa). According to Wikipedia, the acute toxicity of these is very low, and large quantities must be ingested to cause “perceptible health damage in humans.” Imperceptible health damage is of course nothing that need concern us.

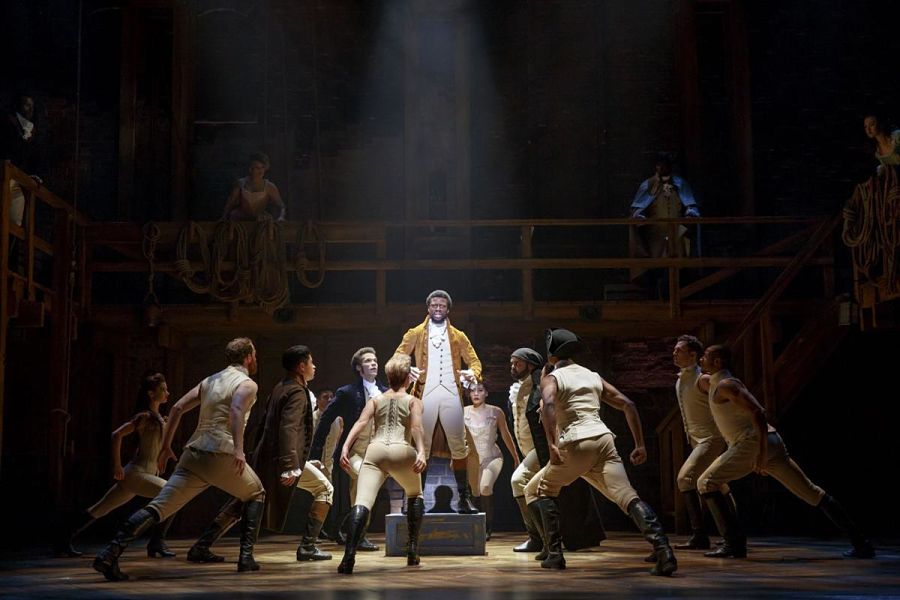

Haze, on the other hand, is made of “white mineral oil,” a highly refined petroleum-based substance. The haze which permeates every scene in Hamilton, and with it the entire Richard Rodgers Theatre, for example, was made by a Canadian firm, MDG Fog Company, “Generateurs de Brouillard,” according to Max Frankel, the show’s electrician. The spec sheets available on the company’s website, mdgfog.com, report that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, (OSHA) does not consider the product hazardous (a “keep out of reach of children” triangle with a black exclamation point on the canister notwithstanding). No significant critical effects or hazards are known from inhalation, eye contact, skin contact, or ingestion, though I’m not sure I’d want this oil in my Dijon vinaigrette.

I’ve never met an actor who liked working in this gloomy pea soup; you don’t hear actors exclaiming, a la Robert Duvall in Apocalypse Now, “Ahh, I love the smell of theatrical haze in the morning!” It’s not pleasant, haze, though most of the time you don’t notice it. And since it appears not to be bad for you, no one complains. But bear in mind, “no known hazards” is not the same as “good for you.” You won’t see hospitals administering tanks of stage fog to the elderly.

I was a subject in a study of the effects of haze during the late 1990s, as a member of the cast of Titanic, the musical. The study examined our vocal cords before and after performances of that moderately hazy show, and several others, and found no signs of irritation worth mentioning.

So no, I will not be attacking the use of stage fog from the standpoint of health concerns in this piece. I, like the EPA under the current administration, wouldn’t have a leg to stand on. The fog of theatre is clearly not as deadly as the fog of war, although it might be used to depict it scenically.

Nor do audiences find fog hard to take, despite the occasional cough. When I was a stage manager for CSC Repertory’s 1974 production of Edward II, I forgot to turn off the smoke machine one matinee, and the audience and actors were forced to evacuate the theatre amid much coughing and gagging. But that was the old days, when powdered smoke was burned in a coiled ceramic heating device. This medieval procedure may have been effective for Edward, but whatever health risks were involved don’t apply to the modern methods.

No, as much as I dislike breathing the stuff, my objections here will not be medical, but aesthetic.

It has been quite a while now—maybe three decades?—that stage fog has been essential in every production with the budget to afford it. Lighting designers love it. It makes their beams of light cut lusciously through the atmosphere; it shows off their fancy vari-lites and computer controlled multiple beams, as they split, come together, and perform spectacular motions in the air. Dappled light from gobos shows up with great effect; candy-colored light beams can dance in the space above the stage, a dazzling display for the viewers.

So what’s the problem, if fog supposedly isn’t harmful, and it makes the stage pretty?

Well, first of all, maybe it’s just because I’m an actor, but I always thought light was supposed to illuminate the thing being lit, not draw attention to itself. In a few productions I have found myself admiring the luminous beams, and missing for a few seconds something that was happening in the play. This is simply distraction, and as Shakespeare might say, it’s “villainous,” showing a “most pitiful ambition in the fool that uses it.” The designer is showing you their genius, but you are watching the air above the stage, not what is on the stage.

Distraction is one of the things directors have to worry about, and, to be honest, it is usually actors, myself not excepted, who perpetrate it. But I have never met a director who wasn’t at least a bit enthralled by gorgeous gestures of light, which are usually larger than any actor’s arms by several orders of magnitude.

Now, fog dissipates pretty rapidly. In Carousel’s wharf scene, the fog is so dense at the top that the scene might be mistaken for a musical of Backdraft, but it is mostly gone in time for Renée Fleming to sing her gorgeous rendition of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” without looking like she she just exhaled a drag of a Virginia Slim. But haze, which is used more often, is designed to hang around so that the lights will be equally dazzling in all the scenes. This is fine if your play has a single set. But since haze lingers longer, you can’t just have it in one scene for which it might be appropriate—a rest stop outside a power plant on the New Jersey Turnpike, say—and then clear it in time for another scene where it might not be, like on a desert plateau in New Mexico. No, with haze, every scene, regardless of location or atmosphere, is equally smoky.

And smoky is the right word. A glance at the beams shows the mineral oil, in haze form, swirling around in the light, like the smoke from Edward R. Murrow’s cigarette in Good Night, and Good Luck. A gesture within a gesture, you might say.

This in turn creates a gauze effect. At times a gauze drop is brought in downstage in a proscenium theatre, as something to project images or printed information onto. The action of the play is still visible behind the drop, but there is looking-through-a-veil effect, as if there were greater distance between the actors and the audience, like blurry memory scenes in movies. With theatrical haze, you get a kind of constant virtual gauze. And since the density increases with distance, the farther you sit from the stage, the more blurry everything becomes.

To be sure, this is sometimes desirable. But what if it’s not? What if you want to minimize, not increase the sense of distance from the action? You may have a fight with your lighting designer on your hands.

Finally, there’s just the truth that stage fog is already passé. It has been for decades. It’s just so…’80s. It’s so Les Miz. So Cats. Someday soon a lighting designer is going to light a show without using it at all, and it will be like a revelation. Critics will rave: “The crystalline clarity of the production is as refreshing as a dry martini.” “There was such definition in every moment!” Audiences will cheer: “I could see the actor’s faces, from the back row!” “I didn’t cough once!”

Come on, lighting designers and directors. I dare you to break the mold. It’ll make your name. You can always go back to it, if you’re doing a play about the Battle of Gettysburg; you can smear cannon smoke all over the Winter Garden Theatre. But if you’re doing, oh, I don’t know, a revival of On A Clear Day You Can See Forever, maybe try showing an actual clear day? The actors will sing your praises, for what that’s worth.

Really, we will. If we wanted to work in smoke, we’d have joined Ladder Company 54, the Broadway district fire department. As it says on the engine, they’ve never missed a show.

William Youmans is a stage actor and singer, best known for originating the roles of John Jacob Astor in Titanic: the Musical, and Doctor Dillamond in Wicked.