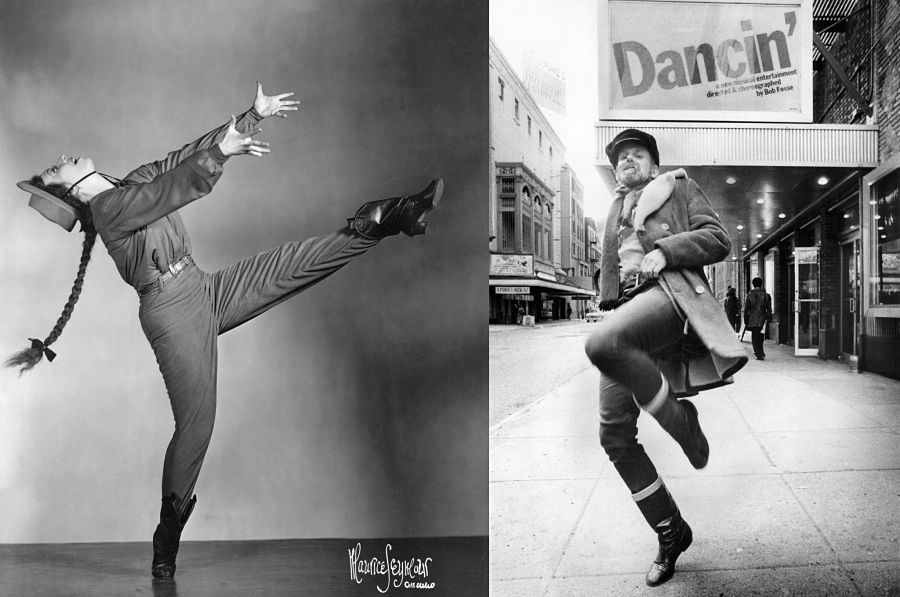

Game-changing dance-makers Agnes de Mille and Bob Fosse rank among the top three American musical theatre choreographers of the 20th century (the third giant being Jerome Robbins). The pair’s creative heydays were separated by just a decade or so, as de Mille made her mark in the 1940s, beginning with her groundbreaking narrative dances for Oklahoma!, and Fosse pioneered his distinctive dance vocabulary in the 1950s and 1960s. Though he reached the peak of his popularity in the 1970s, Fosse built all his choreography out of the same movement lexicon he began showcasing in the memorably vaudevillian “Steam Heat” trio from The Pajama Game (1954), Gwen Verdon’s star turn performing the satirically sexy “Whatever Lola Wants” in Damn Yankees (1955), and the stylish ’60s-fad-dances-inspired “Rich Man’s Frug” from Sweet Charity (1966).

Why, then, does de Mille’s choreography seem so dated now, while Fosse’s still looks as fresh and provocative as ever? It’s particularly puzzling considering that de Mille was the more revolutionary of the two. She created a startling new approach to integrating dance into the musical via character development, and established the standard for the widely imitated (and later much-parodied) “dream ballet,” an expressionistic choreographic sequence probing deep into characters’ psyches. Moreover, de Mille’s dancing characters were often women, and for the first time in Broadway musicals, lyrical dance was giving centerstage to women’s inner thoughts and feelings.

Fosse’s great contribution to Broadway dance, on the other hand, is largely limited to his creation of a compelling physical vocabulary, so intriguing as to be embraced by all kinds of movers, copied by countless choreographers, consciously or not, eventually achieving such iconic status that it permeated the larger visual fabric of pop culture.

I’d say it’s because of our radically changing notions of gender roles that Fosse’s choreography still looks fashionable, while de Mille’s feels like it came from a bygone era. De Mille’s dances reflect a decidedly binary understanding of gender, where women are strictly feminine and men are indisputably masculine, each group performing its own kind of movements, with gender-specific gestures, impulses, and energies. Fosse’s dancing bodies, on the other hand, share a common physical vocabulary, often exuding an androgynous sexuality that aligns more easily with our new, increasingly fluid notions of gender identity.

Both part of the Broadway Legacies book series published by Oxford University Press, Kara Anne Gardner’s Agnes de Mille: Telling Stories in Broadway Dance and Kevin Winkler’s Big Deal: Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical shed much analytical light on the dances created by these two towering choreographic figures. Chock full of step-by-step descriptions of the multitude of dances they choreographed for Broadway musicals, the two solidly researched books reveal much about their subjects’ differing approaches to gender expression. Winkler tells us that Verdon, Fosse’s muse and third wife, once said of her husband, “He’s very sensual and he thinks movement is the same for men and women. The only difference is that women wear high heels.”

Tellingly, de Mille dismissed Fosse’s choreography as “just gymnastics, squirming around….I never thought it was possible to take sex out of eroticism, but that’s exactly what Fosse does.”

Gardner’s book luxuriates in rich explanations of how de Mille’s eloquent, character-driven dance sequences spotlight women’s perspectives. The Civil War ballet from Bloomer Girl (1944), for example, shows nothing of battlefields, focusing instead solely on the emotions and experiences of the women waiting back home.

In drawing her nuanced dance portraits of women, Gardner notes, de Mille frequently invented secondary characters for members of a show’s dancing ensemble. She did this most notably in Oklahoma! for Joan McCracken, a bewitching comic dancer who later married and mentored Fosse, jump-starting his career as a Broadway choreographer. Gardner argues that these secondary characters established important dramatic threads that, along with the other thematic, tonal, and narrative contributions made by her dances, support de Mille’s pioneering contention that her work as a choreographer be recognized as “authorial,” alongside that of a show’s composer, lyricist, and librettist.

Themes of authorship and collaboration, key topics in the highly cooperative field of musical theatre, run prominently through both books. We learn how de Mille and Fosse were each plagued by contentious relationships with producers and fellow members of the creative teams of the musicals they choreographed, each of them waging fierce battles for credit and control of their work. While trailblazing the portrayal of women onstage, off-stage de Mille fought ferociously for equal pay and treatment in an era when those granted artistic leadership roles on Broadway were almost exclusively men.

Serious musical theatre enthusiasts will want to spend time with both of these worthy books, as they offer close-up examinations of the remarkable dance-makers’ oeuvres, and are seasoned with a modicum of relevant biographical information. Gardner’s is a penetrating work of insightful, tightly focused scholarship, with a full chapter devoted to each of six de Mille shows: Oklahoma!, One Touch of Venus (1943), Bloomer Girl, Carousel (1945), Brigadoon (1947), and Allegro (1947).

Winkler’s sluggish tome, I’m sorry to say, is an unentertaining chronicle likely to sit on one’s shelf of valuable reference books. Though he provides a welcome complement to Sam Wasson’s Fosse—the juicy 2013 biography that doesn’t adequately recognize the monumental influence of the choreographer’s seductive movement vocabulary—Winkler plods chronologically through Fosse’s work with exhausting predictability, walking us through every movement of every dance number from every show, film, and television special Fosse choreographed. Somewhere around Pippin (1972), my endurance began to flag, and every dance began to sound the same.

This is not entirely Winkler’s fault, and it actually underlines an important point: Fosse’s repetitiveness. Despite the brilliance of his work, Fosse was often justly criticized for recycling the same movements in dance after dance. Unlike de Mille, whose choreography derived from the particulars of each musical’s story and characters, Fosse imposed his personal movement style upon whatever show he choreographed. This doesn’t mean his dances did not support the narrative fabric of those shows. They did, but only because he was careful to select dramatic material that suited his choreographic visions.

Winkler offers little in the way of original thinking or new perspectives on Fosse’s Broadway choreography, employing choppy prose to periodically summarize gobs of knowledge garnered from research by authors of secondary sources whom he doesn’t always credit. For all that, though, Winkler does provide excellent analysis of Fosse’s dance vocabulary. He picks apart every component of Fosse’s signature style—the hunched posture, turned-in legs, provocative isolations of body parts, highly charged eroticism, rhythmic accents, amoeba-like clumps of moving bodies, snazzy vaudevillian tricks—and identifies where, when, and why they worked their way into Fosse’s choreographic language. Any reader who digests Winkler’s work in its entirety will come away able to dissect Fosse dances with ease and authority.

And those who read Gardner’s more streamlined volume will look with greater appreciation at de Mille’s storytelling choreography, and perhaps consider anew the plights of the women characters telling those stories. While fusty in their gender depictions, de Mille’s dances should serve today as stinging reminders of how important it is that female voices be heard.

Lisa Jo Sagolla is the author of The Girl Who Fell Down: A Biography of Joan McCracken and Rock ’n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s.