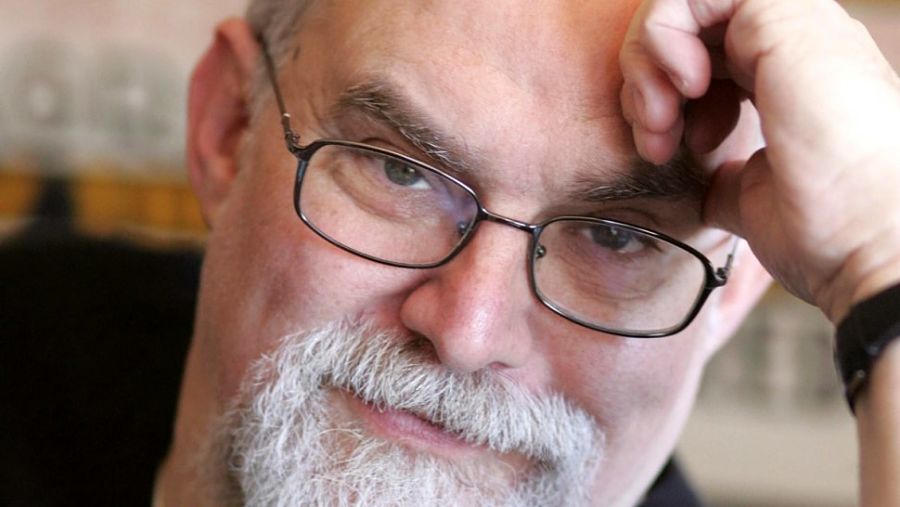

“I wanted to write a love letter to the theatre, and that’s what this is,” says William Finn of his new musical, The Royal Family of Broadway. But he quickly qualifies that statement, calling it “kind of a dangerous love letter to the theatre.” Putting aside a luncheon salad, he relaxes into an easy chair in his sunny Upper West Side apartment, and continues, “It’s not full-throated. It’s an equivocal love letter.”

Finn, whose musicals often spring from his own experience—March of the Falsettos, Falsettoland, A New Brain—has rarely used previously produced material as a starting point. An exception was the Off-Broadway musical Little Miss Sunshine (2013), adapted from the popular film. The Royal Family of Broadway, which begins performances at Barrington Stage Company in Pittsfield, Mass., on June 7, is the first time Finn has used a classic play as a source, in this case George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber’s 1927 comedy/drama The Royal Family, which Finn calls “a beautiful, lovely romp.” The play centers on three generations of the Cavendish family, a theatrical acting dynasty inspired by the real-life Barrymores. There’s matriarch Fanny, daughter Julie, and son Tony, a Hollywood screen idol, as well as Julie’s daughter Gwen, whose fiancé is not in the business. (Fanny’s opinion about that is delivered in a song called “Marry a Man of the Theatre.”)

Also on hand are Fanny’s brother, Herbert Dean, and his wife, Kitty; Herbert has a play in hand and wants Julie to star opposite him, but Kitty thinks she should have the part. As the titles of both play and musical suggest, the characters’ behavior in real life parallels their grand manner onstage.

The rights to The Royal Family have been in and out of Finn’s hands for more than a decade. In readings of the musical held in New York City in 2000 and 2001, Elaine Stritch played Fanny alongside, variously, Carolee Carmello, Laura Benanti, Tovah Feldshuh, Donna Murphy, and Brent Barrett. Then came a setback: With 60 percent of the score written, Finn lost the adaptation rights to the play, which the Kaufman estate gave to another party. Finn’s work was put on the shelf.

After he secured the rights again in August 2012, the project was revived, with Rachel Sheinkin, Finn’s collaborator on The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, tweaking the book originally supplied by Richard Greenberg (Finn’s Falsettos colleague James Lapine also took a whack at it). Spelling Bee also originated at Barrington Stage, where Finn and artistic director Julianne Boyd established an annual Musical Theater Lab in 2006, giving selected young composers and lyricists a summer in the Berkshires to work on their musical projects under Finn’s guidance.

Ironically, when Finn first acquired the rights to The Royal Family, he had never seen a production of the play. The attraction, he says, was the theatre milieu “and these huge characters that would be fun to write for.” The Cavendish family are examples of a theatrical type that flourished in the early 20th century, captured elsewhere by larger-than-life personalities like Garry Essendine in Present Laughter or Oscar Jaffe and Lily Garland in Twentieth Century.

Few performers now evoke that kind of high style, though Finn, 66, recalls that brushes with late greats Ellis Rabb and Marian Seldes gave him hints of that breed. At mention of the latter (who played Fanny in a production at the Williamstown Theater Festival in 1996), Finn explodes: “Marian Seldes! Was she great!” Still, he remembers that that wasn’t his first impression of her work. “I saw her in Equus, and I thought, ‘That’s overacting.’ And then I grew into her way of acting,” he says. “I mean, everything she did was more brilliant than the last!” At Barrington Stage Harriet Harris is taking on Fanny; the other Cavendishes are Laura Michele Kelly as Julie; Will Swenson as her brother, Tony; and Hayley Podshun as granddaughter Gwen.

Finn’s affection for the characters is shared by Sheinkin.

“Large emotions work well in musical theatre, and people who are self-dramatizing are fun,” she says, adding that Greenberg’s book “was already great, and the funniest parts, if they’re not from the Kaufman-Ferber, then they’re from Greenberg.” This version, though, adds some musical-theatre connections to the Cavendish résumé, including a sly mention of Show Boat, Ferber’s other 1927 hit, which opened the night before The Royal Family.

“We made Gwen a dancer,” says Finn. “Her love interest dances too. We’ve incorporated some scenes at the theatre that obviously aren’t in the play.” And, Finn says, he took up the challenge of trying to write in the style of 1930s music, adding, “I hope you can tell right away it’s William Finn music!”

For her part, Sheinkin has had to fine-tune the text to support the score. “The hard part of a book is that you’re looking for it to work as a whole,” she explains. “And sometimes you have only a couple lines here and there to adjust the characters throughout the show.” An example? “Anyone who knows William Finn’s work knows that he’s going to follow a good rhyme where it leads—so suddenly a good rhyme has changed your plot or some significant thing about this character.”

There’s another balance for Sheinkin to strike: Unlike Kaufman’s more farcical collaborations with Moss Hart, such as The Man Who Came to Dinner and You Can’t Take It With You, the Ferber collaborations, which include Stage Door, have a higher proportion of serious material. The question for Sheinkin, then: “How do you keep it light and still have something substantial underneath, so that it adds up to feeling like more than the sum of its parts?” She notes that both Greenberg and Finn are “good at writing humor on a sea of pain, and this is not a show that you want to drown or indulge in that sea of pain at all. We are celebrating some old-fashioned joys here: song and dance and the craziness and deep connection of family, and people with extreme passions acting selfishly.”

Finn says he is excited about the show’s future prospects; the show does have “Broadway” in the title, after all. There is even a producer who has expressed interest in bringing it to New York, he says. But he counts himself ambivalent about the present state of musicals. Asked if he enjoys them as much as he used to, he exclaims, “No, absolutely not!” Then, more calmly, he qualifies his outburst: “I enjoy good musicals more than I used to, knowing how difficult they are to write, and just to be able to see how they are created and everything. But seeing a bad musical—I used to love going to theatre and seeing anything. I don’t enjoy that any more, at all.”

It’s been his good fortune to find success in the art form, but Finn also gets satisfaction from teaching a course in writing musicals at New York University, from the summer lab at Barrington, and from writing song cycles, which he has been thinking about lately. “I have song cycles in my head,” he says, calling 2003’s Elegies “the best writing of my life.”

As for musicals, he says, “I was just born into them. I had to actualize my love, but eventually it turned out the way it was supposed to, and I wrote musicals because that’s what I was supposed to do.”