It’s a five-hour drive south from Portland to Ashland. The trip takes you from just south of the Washington border to just north of the California border, almost the entire length of the state. For those coming north from the Bay Area it’s also about a five-hour drive. And each year around 400,000 people make the trip, most by car but a few by plane, to visit this small city tucked up in the foothills of the Siskiyou and Cascade ranges. And they do this because they want to see theatre.

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival looms large in the Northwest theatre scene. There’s a reverence for it. But it also looms large in the cultural landscape of Oregon itself. People who don’t see theatre know about OSF by reputation. This reputation is well earned. The organization has been in existence for more than 90 years and put on thousands of productions. It has grown from a small summer festival to an outdoor stage to a behemoth repertory company with three theatres running multiple shows per day almost all year long.

When I was offered the chance to visit I jumped at the opportunity. This is not a trip I would be able to afford on my own. The decades of hard work OSF has put into its growth, and the simple fact of its geography, make it a destination theatre. The festival’s own statistics show that 80 percent of attendees at OSF have traveled more than 125 miles to see the shows.

I wasn’t sure what to expect out of my first show, but nothing could have prepared me for Destiny of Desire. Karen Zacarías’s script is a dizzying combination of telenovela, musical numbers, Brechtian aesthetics, social commentary, untranslated Spanish, and Shakespearean tropes. I know that sentence sounds pretentious, but this is the most unpretentious show I’ve seen. The script, the performances, the minimal but dazzling design—every aspect of this show just wants the audience to have a good time. There’s a tendency for artists to think that entertainment and “good art” are mutually exclusive. But Destiny of Desire is unabashedly fun. That doesn’t mean it’s light on substance—genuine moments of pathos and smart commentary are abound. But it overwhelms you with excitement. (And it centers a Latinx experience.)

Several times throughout show I gasped audibly when yet another scandalous secret was revealed. My reactions were mild, though, in the audience I was with, which was full of high school students who had been bussed in. They cheered and whooped constantly throughout the show. Normally I would scowl at audiences like this, but they were in fact the perfect audience to see this show with, eager and enthusiastic. During intermission my travel companion overheard one teenager excitedly say to another, “It’s so inclusive!”

Walking out I just wanted to watch the entire show again. Or a series of telenovela plays just like this. Shows like Destiny of Desire make theatre feel joyous, vital, and welcoming.

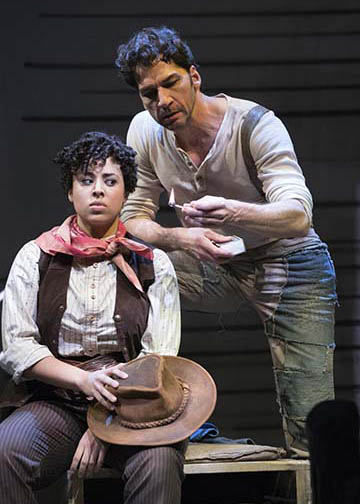

The next day, after a very Instagrammable and delicious brunch at a place called Hither, we saw Oklahoma! I have a fondness for this show because it was the first musical I ever saw. OSF’s production recast it as a multiracial, LGBTQ utopian fantasy, and I also have a fondness for those. So this show is pretty much exactly what I was looking for.

This was more than director Bill Rauch deciding to do “gender blind” casting. OSF got special permission from the Rodgers & Hammerstein organization to change Curly to a woman, putting a lesbian romance at the center of the show, and Ado Annie to a man, making the B subplot a gay romance. In addition to the same-sex couples, the production integrated bisexual, transgender, and genderqueer identities into the show. Combined with the feel-good optimism of the music it, felt like this was a world we could aspire to.

This reimagining of an American classic is something I’d like to see more of, especially at theatre produced at this level. How many more traditional productions of American classics do we really need? Why not let artists experiment with these shows, and make them more reflective of the country? Why not let people see themselves represented onstage? That said, changing a few pronouns can’t fix some of these old shows’ problems. I always forget how dark and nonsensical “Pore Jud Is Daid” is: Curly literally tries to convince Jud to kill himself so that Laurey will go to the box social with him.

It wouldn’t be OSF without a Shakespeare play. I was given the choice of Henry V or Othello and I chose Henry V because it’s not a show that I see get put up very often. I…liked it. Indeed it was probably the best production of a Shakespeare play I’ve seen in a long time. Henry (Daniel José Molina) captured both the tenderness and bravado of a young man thrust into power. The design was pared down but with great attention to detail. The staging was dynamic. The visuals were striking. The casting was wonderfully diverse.

But when I compare it to the other shows I saw, especially after I finished my weekend with Manahatta, it just didn’t feel dynamic. Shakespeare’s work still feels abstract to me—general. It was written for a specific audience in a specific time and place. While his work deals with ideas that still resonate today, I find that translating it to the time we live in now less interesting than current or contemporary work responding to the world I inhabit now.

Out of the 11 shows this season at OSF, 4 are by Shakespeare and one is a show about Shakespeare (The Book of Will). It would be hard to imagine a company with Shakespeare in the name not producing his work, of course, and I’m sure it’s still a big draw for many of the people who choose to make the trip. But in my experience it’s not the most interesting work OSF is doing. What’s important to me is that by producing Karen Zacarías alongside their festival’s namesake, OSF is essentially telling audiences she is just as important as Shakespeare. Raising the profile and prestige of living playwrights, especially from marginalized communities, may be a challenge to their traditional audiences—but without that mission, this Shakespeare festival would be little more than an escape for the wealthy.

Where Destiny of Desire and Oklahoma! are thrilling and buoyant, Manahatta is deliberate the thoughtful. Mary Kathryn Nagle’s story follows a young Lenape women who lands a job in investment banking in Manhattan, the traditional homeland of her tribe. The script is intricately constructed, weaving together the past and the present, capturing the heartache and resilience of Native peoples in the past as well as the present, the ravages of unchecked economic systems, and the significance of language.

Oregon has seen three world premieres of plays by Native women this year as part of the Indigenous Women Playwrights Series. The Thanksgiving Play by Larissa FastHorse and And So We Walked by DeLanna Studi had their world premieres in Portland. Raising up indigenous voices is a trend that needs to continue both here and across the country.

Manahatta is particularly interesting juxtaposed with Oklahoma!. While the latter presents a fictional utopia devoid of the conflict between Native nations and manifest destiny, Manahatta presents a very realistic presentation of our country’s history of colonization. This makes a weekend in Ashland unique: Each show informs how you think about the others. Despite the very different energies of these two shows, together they left me with a feeling of possibility: that indigenous people they will find ways to thrive. That LGBTQ people will live open lives. And that we all have a part in making that happen.

I appreciate that OSF is putting up these kinds of shows, and I hope that all those thousands of people who make this trip every year take these ideas back to their hometowns—that they support their local theatres so they can produce good work that can be seen by more people, that they demand new voices and representation, and that they’ll put what they learned into practice.