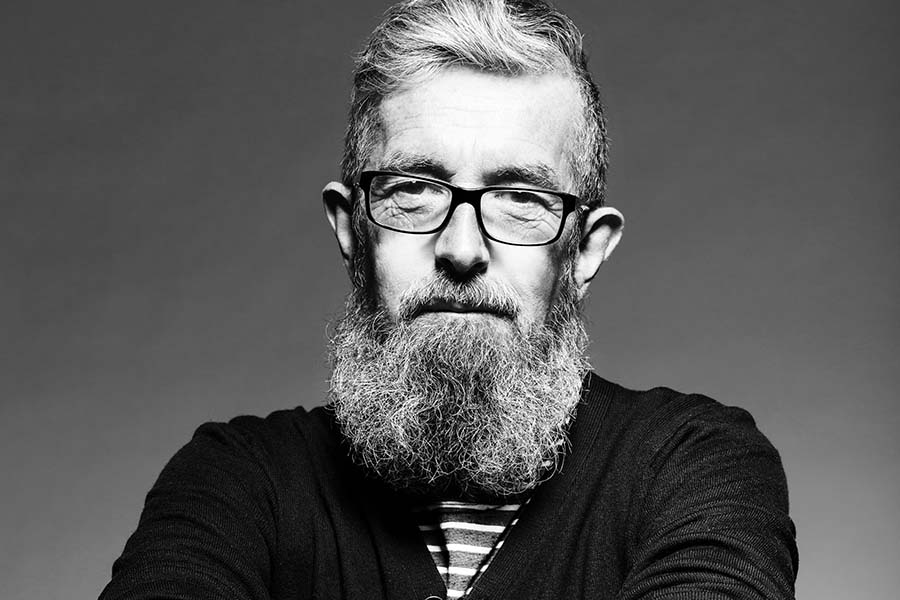

As a theatre director, Les Waters doesn’t disappear behind the playwright’s voice, exactly, but seems somehow to fuse his sensibility to it. So while it may be hard to nail down a Waters aesthetic, given the wide range of work he’s done, it may be instructive to look at the body of new plays he’s had a hand in introducing to the world, from Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice and In the Next Room (or the Vibrator Play) to Anne Washburn’s 10 Out of 12, from Lucas Hnath’s The Christians to Chuck Mee’s Big Love and The Glory of the World. What do these plays have in common? An adventurousness with form and language, for one; also a sense of visual play that’s not merely pictorial but feels distinctly theatrical.

How to characterize his tenure at Actor’s Theatre of Louisville, which comes to an end next month? Obviously, he did not direct all the plays in ATL’s seasons for the past six years, nor all of the plays in its influential annual Humana Festival of New American Plays. But it’s not hard to detect his stamp on Humana selections by the likes of Jen Silverman or Erin Courtney, or this recent season’s almost-all-female crop, or the fact that among the world premieres he’s staged in the non-Humana ATL season was Washburn’s musicalization, with Dave Malloy, of Little Bunny Foo Foo. One must tread lightly with invidious comparisons, but it seems clear that under Waters Humana has firmly regained its preeminent reputation as a new-play showcase.

Waters is leaving the post after just six and half years; he’ll next direct Hnath’s A Doll’s House, Part 2 at Berkeley Repertory, where he once served as associate artistic director, and another new piece of Hnath’s at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Los Angeles and at the Goodman in Chicago. I spoke to him recently about his past and his plans.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: The first thing I wanted to confirm was that it’s “Les” with a Z sound, to sound like “Lez,” not “Less.”

LES WATERS: Yeah.

Is that short for Lesley, if you don’t mind me asking?

Yeah.

Though you’re British and still have the accent, you’re not a newcomer by any means—you’ve been here for 20 or 25 years, is that right?

Yeah, full time for 22 years. I first started working in the States, I think in the late ’70s. I did a Caryl Churchill play called Fen that went to the Public Theater in the early ’80s.

Then what brought you here full time?

It was the job offer to head the directing program at UC San Diego; I had for many years before that been working more and more in the States, in regional theatre and in New York. Annie Smart, who is a set and custume designer and my wife—we had three young kids, so we thought it was an adventure and we moved.

I know, I’ve talked to a lot of directors with young kids, and they tend to gravitate toward a home base so they can raise a family in one place.

It’s difficult if you work in the theatre, and in particular if both of you work in the theatre, and you have children. That’s a very complex thing to negotiate. I was at UCSD for eight years, then I moved to Berkeley to be the associate artistic director of Berkeley Rep for eight. I’ve been here in Louisville—I leave the end of June and I will have been here six and a half years.

What were your impressions of U.S. theatre when you came here and started working here full time? And how do you feel it’s changed since then?

I’ve found it very exciting being here. I’m British by birth but I don’t feel a huge attachment to my home country. Personally I’ve always enjoyed the opportunities that have come my way and felt a real sense of growth on a personal level in what I’ve been able to do. I’ve always thought it was exciting, and now I find it even more exciting, though we live in very tumultuous times where it’s both exciting and some days it’s like, “Jesus, fuck, what is going on?” I find the work that people are creating to be enormously interesting.

You feel like it’s in dialogue with what’s going on in the country and in the world?

I certainly do.

You got your start with Joint Stock in England, and you’ve passed on that tradition of ensemble theatremaking to a few generations of American theatremakers—the Civilians, for one. Was that a conscious effort, to continue that heritage with your students?

I did work with Joint Stock; my first experience of working with them was as the assistant director on the original Cloud 9. Then I did Fen and A Mouth Full of Birds with Caryl Churchill and David Lan, and other pieces. That way of working, and that sense of ownership by the group of the material, was profoundly important to me. When I was at UCSD, I think the class was actually called Joint Stock; all of the MFA first years participated in a class where we would, in a sense, research something, edit the material, then give one presentation. Steve Cosson was in that class, Anne Kauffman. Was it deliberate? It probably was.

Well, if the class was called Joint Stock…

Yeah, it was saying: This is a valuable way of working, where you can create material on your own, and there were things that were often hidden from history that we don’t look at—things that have been pushed to the periphery, so why don’t we take a look at them? I know there are now social platforms where you can yammer on about your own life, but this was a way of giving voice to people who had maybe not been given that opportunity.

So Joint Stock was not just an aesthetic—it was an ethos of a kind of theatre, what the theatre was about. Would you say that being part of that company gave you an attitude or approach to what a theatre company ought to be, and do think you brought it into this job? Or was there a completely different skill set required to run this kind of nonprofit theatre?

It’s also a huge jump from being an associate artistic director, which I’d been at Berkeley. Just in terms of the relationships—with the board, with donors, with patrons. You become a public face for the building. Your aesthetics and what you think is interesting can really help define what the building is, and because I think most directors have a team of artists they want to create with, once that team begins to start working in a building, it causes shifts in the way the building operates and how the work is seen to the public who come to see the work.

So you feel like that has happened at Louisville?

I think so, yes.

By the standards of some artistic directorships in the American theatre, yours hasn’t been the longest tenure that can be imagined. Are you leaving now because your work is done, or you just have other things you want to do?

Last year I turned 65. I didn’t wake up on my 65th birthday with an angel in my room saying, “Les, what are you going to do next?” I had been thinking for several months before that, well, 65 is a big age and it’s a symbolic number. What am I going to do? I’ve been working in the theatre for four decades. What am I gonna do with the next part? I do believe in shaking things up for myself and I thought—well, say I’ve got another decade of this. If I’m gonna change it, I should do it now, not drag it on. I felt a personal need for a change and so I decided to leave and go freelance.

Do you feel like the organization has got to a place where you feel it’s in good stead?

I do. And it’s ready for a change.

Someone recently pointed out that you’ve directed a sort of religious trilogy in your time at Actor’s Theatre: Lucas Hnath’s The Christians, Chuck Mee’s The Glory of the World, and this season Mark Schultz’s Evocation to Visible Appearance. I know you had a religious upbringing, so I was wondering if you could talk at all about the way this theme has seemed to surface in work you’re interested in, or is it a coincidence?

It would be dishonest to say it was planned. I’m not religious now, but I cannot deny…from the outside they look connected. When somebody here at the Humana Festival said they thought Mark Schultz’s play was in dialogue with Lucas’s play, then somebody said, “There are three of them.” I said, “What the fuck is the third?” They went, “Glory.” And I said, “Oh, you’ve got a point.” It was not a conscious creation. The Glory of the World was a piece that I thought of as directly related to the community, because it was an anniversary of Thomas Merton. Merton is a very important figure in this town, and somebody that everybody has different opinions on. So I wanted to create a piece with Chuck and this company about him.

But all three plays stand there, and I obviously have made something. I can’t quite analyze it; I think it will take me a while to kind of wrestle with the ideas behind them. But I do have an interest in the idea of faith—what does it mean and how do we make decisions about things.

That leads me to a question about what a director brings to a play, especially in the realm of new work, which you’re associated with. To what extent do you feel you have, if not quite an authorial voice, but an influence as a person and a director on the work that writers do?

It’s difficult to talk about. I certainly think I direct, I don’t interpret. But—I’m going to use a religious term here—I think I bring some kind of physical vision of life in front of people. I think what’s interesting is that you lose a bit of yourself whenever you direct, and I now need time away to work out what I’ve lost in the process.

Do you feel like you lose a bit of yourself because you’re serving someone else’s vision, or that it’s such a collaborative process, a management job that takes up so much time?

No, because I think you have to, in some sense, go very deep into it. I think what all companies need to know—I’m now talking more in the sense of a design team and actors—they want and need to know why you need to direct it, what the need is. I mean, you could say, “Just putting it up in space” and “It’s my job,” which of course it is, but I’m not sure that would be wholly satisfying. So I think, and it may be very mysterious, this, that what the actual need is for a director can be quite hidden, and may be potentially damaging. You go through it and you make the piece, and then, for myself, because I’m not quick-witted about this, I need time to kind of evaluate what’s happened. That’s all I can say. I’m sorry if that sounds like mumbo-jumbo.

No, I think I get it. Do you feel this about your whole tenure in Louisville, or just about any production you’ve done—this need to step back and evaluate?

Any production, but I mean, I’ve done several productions here. I really do need time to step back and kind of go, What did this body of work mean? What did it mean to me? I’m not a critic and I can’t evaluate in certain critical ways, but I need a certain emotional rest to think, okay, well that was that, and now where am I launching myself into?

You said a moment ago that you direct, not interpret. I’m wondering if you can tease that out. I don’t know your résumé well enough to know what extent you’ve done work by dead playwrights…

Well, I did the Scottish Play here. I think people think directors interpret work. I resist the idea of directors being in a secondary role. I don’t think I interpret it; I think I’m an equal collaborator, and I bring a vision of the work to life.

You are thought of as a new-play director primarily, though, which is why it makes perfect sense that you’ve been at the theatre with the Humana Festival. How do you think Humana fits into the new-play ecosystem, and do you feel that’s changed over time?

I think it was the place, then it was one of many new-play festivals. And I think that all during my time here we’ve done extraordinary work, and we’re the new-play festival.

A lot of us who know Actor’s Theatre just for the Humana Fest can forget there’s a whole season going on there year round. I think you’ve put it this way, that the Humana Festival is like putting on a whole season in a month or two, right?

It’s exactly like that. We do a season, and then we do another season at the end of that.

So we can really call yours a 12-season tenure, right? I don’t have any other questions, but I do want to add that I am a staunch admirer of your beard.

Oh, thank you. It surprised me.

Really?

I didn’t have a beard for many, many years and then I did Sarah Ruhl’s adaptation of The Three Sisters at Berkeley, and all the men were like, “Please grow a beard.” I thought I’d try it in solidarity with the men. This beard appeared.