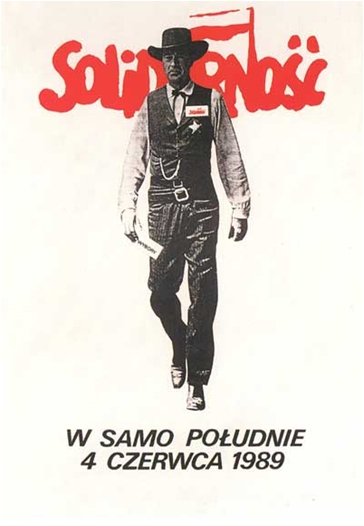

“Cowboys had become a powerful symbol for Poles. Cowboys fight for justice, fight against evil, and fight for freedom.” —Lech Wałęsa, speaking about the famous Solidarity poster that helped him win the Polish presidency

If you had been there—in Warsaw, in the turbulent spring of 1989—there are certain things you would understand better than those who weren’t.

I have a professor friend who was teaching there at the time. She witnessed the workers’ strikes, the turmoil, the fiery speech-making of that February, March, and April. She heard Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa address a cheering throng on the banks of the Vistula. That was some 29 years ago, but my friend never tires of talking about the electrifying atmosphere and patriotic intensity of those game-changing days in Warsaw.

By the time she left Poland that June, anti-Communist candidates from the Solidarity party had won heavily in the Polish parliamentary elections. And by December of the following year, Wałęsa himself had become Poland’s first freely elected head of state in 63 years.

Los Angeles-based writer and director Nancy Keystone was not in Warsaw in 1989, watching the precipitous advent of Polish democracy; she was in her early teens at the time. Her first visit to Poland came two decades later, on the occasion of the Year of Grotowski, a celebration of the influential Polish avant-gardist, which she attended in the company of theatre scholars and practitioners from around the world (this writer included).

But that 2009 trip, it’s safe to say, was a life-changer for Keystone. She immediately felt an intense attraction to the country, its artists, and its cultural outlook.

“I was struck by the primacy of theatre in Poland, the value placed on it—that was in stark contrast to how theatre is perceived and experienced in the U.S.,” Keystone avows today. “I was immersed in an intensity of energy that I’d not experienced in many years.”

Some long-range artistic gears began to grind. Keystone was hooked, and over the next three years she headed back to Poland five times. Those multiple pilgrimages may not have made the same emphatic imprint on Keystone that my talkative professor’s 1989 sojourn made on her—being there at the birth of a revolution is, after all, a one-of-a-kind experience. But Keystone’s more recent Polish excursions have resulted in a rich array of connections and exchanges for the director, and for the award-winning experimental ensemble, Critical Mass Performance Group, that she leads. And those Polish bona fides lend a home-grown authenticity to Keystone and company’s remarkable new work, an expansive, time-hopping piece called Ameryka, which made its official debut (after nearly eight years of development) April 19-29 at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Los Angeles.

It was a poster—a famous one, created in (you guessed it) 1989—that set Ameryka in motion.

“That first trip I took to Poland came on the 20th anniversary of the Solidarity election, so that Gary Cooper poster was on display everywhere,” Keystone remembers. Based on a publicity still of Cooper in the role of Marshall Will Kane, striding down the street in the 1952 Carl Foreman film High Noon, the poster combined the bright red slash of the Solidarność logo with the all-American image of an individualistic cowboy fighting, against overwhelming odds, for justice. The poster was displayed all over Poland in 1989, encouraging voters to end Communist control over the country, and it helped the election catch fire.

Created by a student graphic designer who was 23 at the time (and who, coincidentally, died this year in Warsaw at age 51), the poster shows Cooper armed not with a pistol but with a folded ballot saying “Wybory” (“elections”), and the Solidarity logo pinned to his vest above the sheriff’s badge. The message at the bottom of the poster translates to “High Noon: 4 June 1989.”

“I didn’t think that much about the poster until I was back in the U.S., and, strangely, I ran across a catalog of Polish posters for Western movies that someone had given me years before,” Keystone recalls. “I pulled that catalog out of a box under my desk, and began reading about that poster and the impact of American popular culture and ideas on Poland. It really blew my mind.”

In short order, 1989 became just one in a list of crucial dates that would become an organizing principle for Keystone’s Ameryka, which takes on the unlikely but ultimately exhilarating task of tracking and dramatizing moments of commonality in the relationship between Poland and the U.S. over the past 250 years.

“My idea was do something about the ideals and trials of democracy and the parallels between the two countries,” Keystone elaborates. “It seemed to me that the first strong narrative thread was the relationship between President Thomas Jefferson and the Polish freedom fighter Tadeusz Kościuszko.” The former was a committed slaveholder, the latter was a heroic figure (and advocate of abolition) who joined the colonists’ fight against the British during the American Revolution.

“I was also intrigued by the 1950s, when the influence of American jazz in Poland was at its height,” she adds—a thread that brought into the story a “jazz guy,” based in part on Louis Armstrong and in part on a bass player with the Dave Brubeck band, both of whom took part in a jazz ambassadorship program that sent musicians of that era around the world. One of Ameryka’s funniest and most outlandish scenes involves the “jazz guy” being interviewed by a condescending, race-baiting State Department official.

“That scene is based on Armstrong’s experience of being cleared to go overseas,” Keystone notes. “Armstrong eventually made a jazz musical with Brubeck about those days, called The Real Ambassadors, about having to represent the U.S. abroad, despite our country’s sometimes hypocritical behavior.”

Jumping forward in time, Ameryka noisily evokes the 1980 Warsaw shipyard strike and the formation of Solidarity, playing those events in tandem with a full-scale riff on the American Civil Rights Movement, complete with a raucous church service. Fast-forward again to the Reagan-era Cold War effort to bring the Soviet system down, and to the post-9/11 global war on terror, during which U.S. military officials operated a black site for torturing captives in an out-of-the-way corner of Poland.

Insert encounters with the House Un-American Activities Committee in the ’50s, a side trip to a New York City gay disco in the ’80s, and some behind-the-scenes maneuvering by the morally ambiguous CIA director William Casey; into that weave Anna Walentynowicz, a real-life Gdansk activist who talks about being jailed and tortured; and the mostly silent presence of Native American Chief Little Turtle, in headdress and fringe, as an ultimate emblem of democracy’s blind spots and misdeeds.

Then take a deep breath.

Keystone’s complex tapestry is a unique writerly accomplishment—no theatrical work I know of has aspired to fashion this sort of dancing duet through time between two nations and its citizens. But every bit as important as the writing is Keystone’s directorial consistency (she draws upon a well-honed tradition of American experimental performance) and her scenic mastery (she’s a visual artist and designer as well as a director). These are what make Ameryka both comprehensible and emotionally resonant for spectators.

The influence of artists Keystone cites as her favorites—Ariane Mnouchkine, Peter Brook, and two Poles, Jerzy Grotowski and Tadeusz Kantor—can readily be detected in Ameryka, but the show’s gestural vocabulary owes more to the Downtown New York experimental scene of the ’70s and ’80s and to classic variations on modern dance. Case in point: As the company of nine (some of whom are Critical Mass regulars) speeds through the play’s continual transformations of time and place, they often incongruously carry bricks with them—and we begin to understand the gesture as a symbol of weight, baggage, struggle, potential. If bricks are for building, what structures, what futures, are these citizens and their leaders forging?

Ameryka was widely reviewed during its run in Culver City, as part of Center Theater Group’s annual Block Party series, and it’s instructive to note how various writers tackled the challenge of describing Keystone’s unconventional epic in a single phrase. “A whirlwind tour of U.S. and Polish history” was Eric A. Gordon’s summation in the lefty journal People’s World. Sam Cavalcanti’s USC Annenberg Media report called it a “crash course” in the same subject. Frances Baum Nicholson kept it simple in her Los Angeles Daily News review: “a composite look at the definitions of freedom and democracy.” Leave it to Bob Verini, writing in Stage Raw, to pull it all together: he saw “a psycho-social-historical-political theatrical collage.”

Whatever you call it, Ameryka deserves a wide audience in the U.S. and abroad. “A number of Polish people have seen it, including representatives from the consulate and from education organizations—they seemed to love it,” Keystone reports. Certainly the show’s nation-bonding message will be thrilling to Poles, beleaguered these days by the illiberal reversals of a Trump-esque national administration in which ultra-right Law and Justice Party leader Jarosław Kaczyński exerts increasingly iron-fisted control.

All the same, Poland’s own experimental performance scene has moved so far beyond the classic avant-gardism that Ameryka wears on its sleeve—today’s East European audiences are accustomed to excessive levels of shock and license, in terms of both form and content—that Keystone’s show, despite its emotional richness and intellectual rigor, might look tame there. On one thing, though, audiences everywhere will agree: Keystone’s actors, without exception, are masters of the Polish accent, and of a variety of American accents as well.

That includes a Gary Cooper cowboy drawl that would no doubt remind Lech Wałęsa of the debt he owes to the American film industry—and the politicians who follow in his footsteps of their intimate connections to the American experiment. “The world is one small place,” a character in Ameryka notes in passing, “and all of us are strangely woven together.”

Jim O’Quinn, the founding editor of this magazine, lives and works in New Orleans.