Challenge

To increase accessibility services for Broadway theatregoers

Plan

Create an app that interprets performances for Deaf, blind, and non-English-speaking audiences

What Worked

Programming an accessibility app in a dozen Broadway houses

What Needs Work

Reaching and educating theatregoers used to interpreted performances and other targeted approaches

What’s Next

Getting the app and its software into every Broadway house and beyond

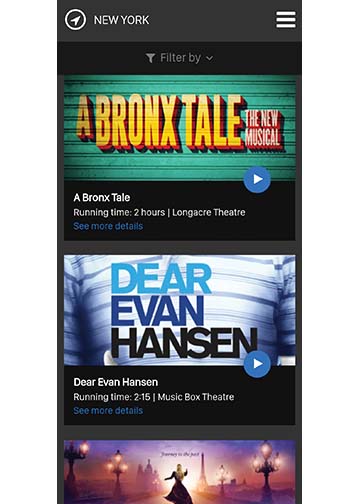

Cell phones in theatres may no longer be taboo. Well, at least in this case, where 12 Broadway theatres now offer GalaPro, a new app that expands accessibility services by providing audio description, captioning, and dubbing to audiences at every performance.

“It actually started when our cofounder wanted to follow foreign languages at the opera,” says GalaPro CEO Yonat Burlin. A globe-trotting connoisseur of the performing arts, Elena Litsyn found herself “unable to follow opera that lacked translation. So we started the research to see if there was a need for a solution.”

Enter GalaPro. Short for GalaPrompter, the Israel-based company started in 2015, and now offers Deaf, blind/low-vision, and non-English-speaking audiences the ability to more fully experience a growing number of Broadway shows at any given performance.

Before the app piloted in select venues in 2016, Deaf audiences were limited to roughly four captioned Broadway performances per month, according to the calendars on TDF (Theatre Development Fund) and handson.org, a website listing Deaf-accessible cultural events in New York City. Audio description performances, where orators articulate design and staging via a personal listening device to blind or low-vision patrons, happen even less frequently. Burlin and her team saw this as a disservice to those communities.

“We wanted to make something where everyone could come together because, culturally, the arts are where we all intersect,” she says. “We started the process with the Shubert Organization, doing online demos—us in Israel and them in New York. Then we did a live demo at Avenue Q with their executives, and now we’re working in every Shubert theatre.”

The free app operates on audiences’ smartphones; those without can borrow an I-Caption device, which works off the same content created by Sound Associates, an audio rental company that provides captioning services. Patrons download the app (“Not everyone knows their Apple password,” Burlin comically laments), then turn off their WiFi to ensure they won’t digitally wander during a performance. From there, users join GalaPro’s separate free network and have the option to hear audio description, listen to dubbing in various languages, or read translations or captions synced to actors’ dialogue via a voice-recognition software, which can follow actors even if they skip a line.

It’s an intuitive app, and one whose creators have thought ahead: “The app emits no backlight,” Burlin says. “We’ve been checking with actors and patrons afterward to see if there were any disturbances, and there really haven’t been any complaints.”

Beth Prevor, who sits on the Shubert’s accessibility advisory committee and is the executive director of HandsOn, agrees. After guinea-pigging the app over the course of its development, she used it as a patron at Come From Away.

“I thought about whether I should tell the people sitting next to me what I’m doing, but then I thought, ‘No, let me see if somebody asks me,’” she says. “I didn’t say anything; I had the phone out with the captioning, and nobody said a word. I had good house seats—center orchestra—and I assume nobody was bothered.”

Disrupting neighbors may be among the more trivial concerns raised by the app. More concerning to some members of the Deaf and blind communities is the potential that one service could replace preexisting ones, such as interpreted performances. Prevor raised these concerns at TDF and the Broadway League’s first-ever Accessibility Summit last November in New York City.

“Our mission was to talk about how it’s wonderful to have GalaPro, but that we shouldn’t forget about interpreted performances and other needs of the Deaf community,” Prevor says. “Someone at the Summit asked if TDF will stop providing open captioning, and they said they’d continue. Sometimes you make these global jumps and lose parts of the community. When we went from interpreting to captioning, people thought everyone can read so now we’ll just offer captioning. And the important thing is that you need to listen to the community; its people are varied in what they need and request.”

JW Guido, artistic director of New York Deaf Theatre, says, “There will always be people, including myself, who prefer open captioning, ASL, or audio description performances over using GalaPro. But GalaPro offers flexibility to those who can’t attend those performances.”

These designated performances offer a sense of togetherness, which is something GalaPro cannot. “I like the community aspect of theatre,” Prevor says. “I like when we do interpreted theatre—I know everybody, everybody is talking to each other, hugging, and that’s why I go. That changes when you go by yourself.”

That’s not the only thing that changes with this every-theatregoer-for-themselves model. For those used to obtaining tickets through Theatre Access NYC, TAP (TDF Accesibility Progam), or other disability resources, using GalaPro also means adopting new theatregoing habits. HandsOn has an e-blast reach of 1,200 subscribers, and Prevor always lists discounts with her site’s featured events.

“I think how you get ticketing info out to the community is going to be a big step,” Prevor states. “In New York, accessibility tickets have been run through organizations, like HandsOn or TDF, not through -TheaterMania or Ticketmaster. You’ve developed this method, and it works. For some people’s entire history of attending thea-tre, we’ve told them this is when you go and this is where you go, and now they can do it themselves. It’s a big teaching curve—there’s this whole world out there now that some have never had access to.

“There’s also safety elements involved,” she continues. “When we do specific performances, the theatres are expecting Deaf or blind people and they’re staffed properly, and now it’s, ‘Go buy tickets and just show up.’ It’s a big jump.”

Still, the greater flexibility GalaPro affords cannot be dismissed. “This is a wonderful step in the right direction to expand accessibility in the theatre,” Guido says. “Art is for everyone.”

Such need for greater access found itself in the public eye last year in a lawsuit against Hamilton’s producers. Mark Lasser, a blind patron, attended a performance but found the venue did not offer audio description, bringing accessibility inequalities to the national spotlight.

The Richard Rodgers Theatre, Hamilton’s host, does not currently utilize GalaPro, but Burlin and her team hope to see the app in every Broadway house by this coming summer. (The app is also looking to expand internationally; Burlin is speaking to venues in London.)

For its effort in developing and implementing GalaPro, the Shubert Organization won the 2018 National Access Award from the Hearing Loss Association of America. And despite the expected bugs and kinks with new technology, Prevor has been impressed with the app’s quick rise. “I’m used to nonprofit, so I’m amazed at the speed and what money can do,” she says. “[The Shubert’s Director of Digital Programs] Kyle Wright says it’s a work in progress—there’ll be glitches and you fix the glitches and you keep going.

“You start it and you learn,” Prevor adds. “It’s not perfect, but if you wait around for perfection you’re never going to get it.”

Billy McEntee is a freelance arts journalist who has written for The Brooklyn Rail, Indiewire, and HowlRound, among others.