Blame it on the times: an era of retrogressive, mean-spirited, and patriarchal politics that leave one in an exhausted state of constant incredulity and fury.

And blame it on the Times: how deeply and daily disappointing that the paper of record erases the same people and perspectives that are ever more disdained by the current regime.

That for me, at least, goes some way toward explaining the outsized irritation—my own and that of many colleagues—that greeted Jesse Green’s recent 5,000-word essay “A Brief History of Gay Theater,” which ran in T: The New York Times Style Magazine on Sunday, March 4. The piece has a perfectly legitimate subject: pondering the meaning, in an age of same-sex marriage, of the revival on Broadway of several decades-old plays by and about gay men, including Mart Crowley’s Boys in the Band (1968), Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy (beginning as three related one-acts, the first at LaMaMa in 1978), Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart (1985), and Tony Kushner’s nonpareil epic, Angels in America (first on Broadway in 1993). Green is an incisive writer whose work I generally admire, and I agree with much of what he has to say about the plays he discusses (and that he discussed in an earlier New York Times article driven by the same query).

But the essay’s framing left many of us wondering if, maybe while we were distracted by one wave of backlash or another, five decades’ worth of feminist, queer, and multicultural critique had been tossed aside like litter from a car speeding down the road to the mainstream. As the pioneering feminist theatre scholar Jill Dolan asked in a Facebook post that quickly garnered nearly 100 approving responses, “Are we really still there, canonizing all the same plays?”

News from the nonprofit arts world of late suggests that we are not only still “there” in a bunch of ways when it comes making diversity a priority, but going in reverse. The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles just fired its chief curator, Helen Molesworth, a lesbian and a progressive feminist who made it a priority to exhibit more women and artists of color there. Meanwhile, in Chicago, trustees shut down the American Theater Company, whose artistic director, Will Davis, one of very few trans people leading an arts organization, was working, as he told this magazine, to “address its whiteness.” A new site for theatre criticism announced itself this week—certainly welcome, but featuring five white cis writers, four of them men.

The word “canon” (or such variants as “canonical” or “canonization”) appears in Green’s essay 16 times with no apparent irony or suspicion. He knows, of course, that making a list immediately invites objections: You forgot so-and-so. You think that play is more important than this one? And he makes a point of acknowledging that “my canon” may differ from others’, though he blithely ignores the glaring difference: Only his glints off the glossy pages of a Times publication, helping to establish the record.

What’s more, without getting into his particular choices, you can’t help but notice its built-in boundaries: Green’s canon takes shape within the closed loop of Broadway and The New York Times, two bastions of bourgie liberalism through which the occasional disruption breaks, as Angels in America did, or as did a lengthy profile in the same issue of T about the radical performance artist William PopeL. The Times lavishes attention on Broadway productions; plays on which the Times lavishes attention have a shot on Broadway.

But why declare canons at all? Their only purpose is to erect gates, as the 1980s canon wars revealed, and protect power, which haughtily declares itself the defender of standards—standards it invented in its own image. The idea of a secular canon can’t help but carry the whiff of its origins in colonialism and control—of the shelf of English books old Lord Macauley proposed to produce a class of Indians to help maintain the British Empire in the subcontinent.

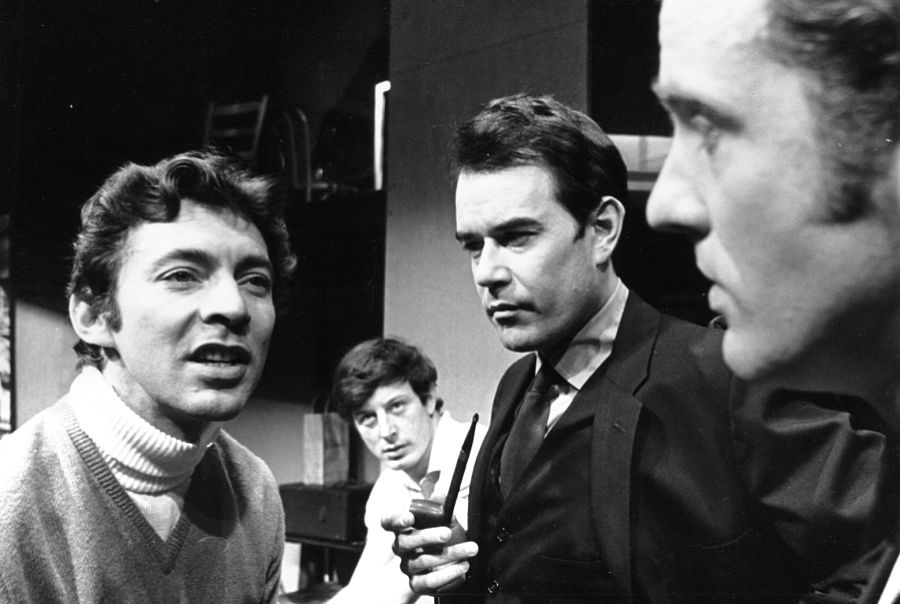

Green’s article appeared in an ad-thick glossy magazine, this particular issue of T focusing on Men’s Style, whose primary purpose is to hawk high-end casual wear, along with the scoop on what looks, brands, art knowledge, and notions confer cultural capital. The magazine’s cover features four of the actors who will be performing in the upcoming 50th-anniversary production of The Boys in the Band, and Green’s article is illustrated with more photos of the cast—all of them out gay men—decked in duds whose designers, and prices, are provided in captions (“Actor Robin de Jesus in a Berluti polo [shirt], $1,010 . . .” and so on).

Okay, sure. It’s a fashion magazine. That’s what they do. But when such blatant luxe peddling is combined with an article that celebrates the normalization of white male gayness on the (largely) Straight (very) White Way, making only a passing, on-second-thought nod to lesbians and people of color—and not even that for trans artists—well, it just felt like a cold slap of evidence for all those warnings from scholars and activists some 15 or 20 years ago about the dangers of looming gay commodification. I’m thinking, for example, of books by Alexandra Chasin (Selling Out: The Gay and Lesbian Movement Goes to Market), Lisa Duggan (The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics and the Attack on Democracy), Urvashi Vaid (Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation), and Suzanna Walters (All the Rage: The Story of Gay Visibility in America). Coming from different angles and not entirely in alignment with each other in every analytical detail, these authors (among others) showed how achieving mainstream “visibility,” becoming a market niche, and being embraced as a chic element of the multi-culti mosaic hardly meant the same thing as liberation and full rights.

And what’s more, they warned that the rising neoliberal project, which combined the touting of market worship and individual responsibility with gay-welcoming social tolerance, would have the same impact on LGBTQ communities as it has had everywhere else: It would exacerbate gender and racial inequality while further immiserating poor people and engorging the coffers of the rich.

Green’s description of the LGBT activism that paralleled—both in responding to and propelling—the gay plays under discussion traces a narrowed line that disregards the radical, intersectional queer politics that has always been a strong strain of our movement (though, admittedly, not in the ascendant these days, alas). Green describes post-Stonewall activism as focused primarily on achieving “respectability” before it morphed into a civil rights movement with the advent of AIDS. Not hardly. Take a look, for starters, at Out of the Closets: Voices Of Gay Liberation, an astonishing collection (edited by Karla Jay and Allen Young in 1972) of the leaflets, manifestoes, and rousing ravings of Stonewall-generation activists who called for the obliteration of gender categories, explained the ideological ties between homophobia and misogyny, and reaffirmed their commitment to the pursuit of racial justice.

For instance, one of the first major activist groups to thrive after Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), which described itself as “revolutionary,” had a broadly anti-capitalist, anti-militarist, and anti-racist agenda and a horizontal method of working by consensus. Dozens of chapters sprang up across the country, and offshoots included the RadicalLesbians, Lavender Menace, and Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries—none could fairly be described as promoting “respectability politics.” Some members of the GLF, objecting to the organization’s support of the Black Panthers, split off to form Gay Activist Alliance, which took a more single-issue focus on LGBT rights but remained plenty in-your-face in its tactics (and also theatre, including the 1972 choral agitprop play by Jonathan Ned Katz, based on documentary material, Coming Out!)

What might “a brief history of gay theatre” look like if its background narrative told a more textured story? Even sticking just with New York in the period between Boys in the Band and Angels in America, it wouldn’t trace just one vector aiming for Broadway. It would include works of antic subversion by the likes of Reza Abdoh, Assurbanipal Babilla, Charles Ludlam, John Vaccaro, and Jeff Weiss; producers and spaces like the Glines, the Other Side of Silence, Medusa’s Revenge and WOW; writers like Kate Bornstein, Jane Chambers, Alexis DeVeaux, Maria Irene Fornes, Gwendolyn Hardwick, Holly Hughes, Lisa Kron, Susan Miller, Dolores Prida, Joan Schenkar, Sarah Schulman, Peggy Shaw, Ana Simo, Megan Terry, Carmelita Tropicana, Paula Vogel, Lois Weaver—a very partial list, and yet—surprise! Not all white guys.

Green evinces what I wish were a singular lack of interest in lesbians. “What gives me pause when I look at my own list of gay male playwrights is not their gender,” he writes about his canon. A beautiful web-only supplement to his essay presents videos of the actors from The Boys in the Band, each reading a poem selected from a group of 10 exciting multiracial, multiethnic writers. Diverse as they are, all of them use the pronoun “he.” At the Times, like the history of queer theatre, the current “golden age of queer poetry” includes no lesbians.

Discussing his article as a guest on the longstanding, indispensible LGTBQ community TV program, Gay USA, hosted by Andy Humm and Ann Northrop, Green comments—prompted by Northrop—on the substantive absence of lesbians from an essay called, let’s remember, “A Brief History of Gay Theatre.”

“I feel like I’m not the person to write that article,” Green demurs. “But I would love to see the article about the way in which plays by or about lesbians developed rather differently from the way these plays by and about men did, and why that’s the case, and what is that canon?” (There’s a fat reading list that any number of people could supply on request, though no need to declare a canon.) Northrop, bless her, pushes back a little: “You write about all sorts of plays. Why not write about those plays?” Green answers: “Well, talk to my editor.”

I hope I just did.