Harvey Schmidt, the composer of such beloved musicals as The Fantasticks, 110 in the Shade, and I Do! I Do!, died on Feb. 28. He was 88.

The first memory I have of Harvey Schmidt is from the University of Texas when he came to audition for the Curtain Club. Tall and skinny, with a pronounced twang, he apologetically explained that he was not an actor, but he loved the theatre and he could play the piano and do posters. Eureka! Actors we didn’t need. Actors we had. (Boy, did we have actors.) But a piano player! A poster maker!

We signed him up and put him to work. The first poster he did was for a play called Beggar on Horseback, and it was wonderful. It was so wonderful that it was terrible: The posters, attached to bulletin boards and tied to trees, were stolen almost as soon as they were put up. People took them and had them framed. (I wish I had done that—I would love to have one.) Not long after, Harvey played the piano and wrote the title song for a Curtain Club revue called “Hipsy-Boo!” Yes, if you’re taking notes, that’s H-I-P-S-Y (dash) B-O-O (with an exclamation point). A wonderful, sassy song. Music and lyrics both. The revue, which was produced in 1950, was a celebration of Broadway musicals from 1900 to 1950, all the way from Gallagher & Shean to “There Is Nothing Like a Dame.” Harvey, in the pit with nothing but a drummer, sounded like a full Broadway orchestra. I was impressed. To be honest, I was awed.

Just a month or so after that show, I got an offer to direct the annual college musical, to be done in the big, 1,000-seat Hogg Auditorium. It paid a fee and I was ecstatic, since this was the first time anyone had ever offered to pay me for directing. However, when I saw the scripts and songs that were submitted by other students, I was appalled. They were awful! Hopeless! And the show was scheduled to open the first week of January, just a couple of months away. Well, I thought: I have to come up with something better than this, so I contacted this Harvey Schmidt fellow and asked him if he would like to write a musical with me. I offered to split the fee. He said yes—and that is how it all began.

We didn’t intend to become writers, either one of us. I was a director. Harvey was a commercial artist (and, as it turned out, a great one, one of the best in America). But that first show we did, written in just a few weeks in time stolen from our regular schoolwork, had a profound effect upon us. It was a hit, a huge hit. It was such a huge hit that the entire 1,000 seats were sold out immediately for its four-day run. It was such a big hit that, for the first time, they sold standing room, and when that was filled up, they sat people in the aisles, and then finally, in response to the overwhelming demand, they opened the side windows of the auditorium so that people could gather in little clumps outside and catch some tiny hint of this magical experience. For that’s what it was: something special. The audience knew it and we knew it too. Something in what we had produced together, cross-pollinating our very disparate talents, was powerful. It made people laugh. It made them weep. And it made them feel a special kind of exhilaration, an exhilaration that they somehow helped to produce along with us.

Time ticks. The world turns. The Korean War erupted and we were drafted into the Army, he in El Paso, me in Baltimore. But because of the lingering memory of that college musical, we kept in touch. We began writing songs by long-distance mail and sending them back and forth across the country. We began to talk about another musical, perhaps a revue, to be called Portfolio. When the army stint was over, we got together in Fort Worth and boarded a Greyhound bus for New York City! We shared an apartment with two other roommates, one of them Robert Benton, who went on to become a four-time Oscar winner as both writer and director, the other a muscle man who left to join Mae West on her final tour. Harvey became an enormously successful, award-winning graphic artist. I languished as teacher to a drama group of middle-aged would-be thespians.

Then The Fantasticks—ah yes, then The Fantasticks. And then. And then. And then. “In so few eye blinks, in transition lightning streaks,” 50 years go by. And then 60. And then 70. Harvey and I have been honored and we have been scorned; we have been pelted and we have been praised. But the point is this: The combination of Harvey’s genius and my talent has left a legacy. All that music which came pouring out of him—directly, it seemed, from his soul—all that still lives. People are singing it right now. People will sing it tonight. And tomorrow. And the day after.

That thing that we felt after the college musical, that sense of something special which we had to give—we were able, by hard work, but also by the grace of God—to nurture and fulfill. Harvey’s life was fulfilled. And I am grateful that, because of him, my life has been fulfilled too.

I am not very religious. I don’t know about heaven. But as I understand it, there is a lot of music there, and if that’s true, Harvey is at home.

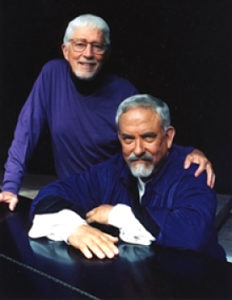

Tom Jones was Schmidt’s lyricist and librettist for several musicals.