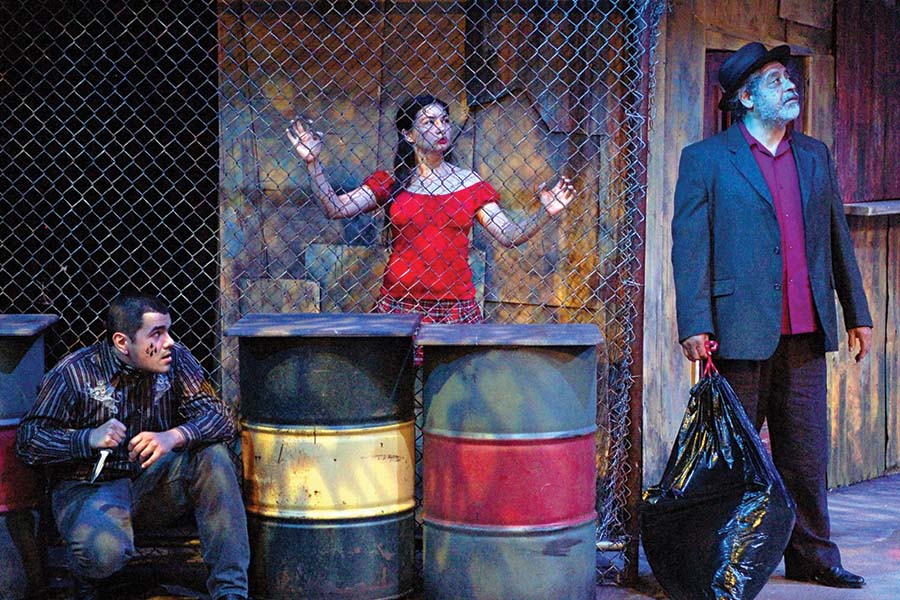

In Hilary Bettis’s beautiful, harrowing The Ghosts of Lote Bravo, Juanda, who works long hours for little pay in a border town maquiladora, goes searching for her missing daughter, Raquel, and begins to uncover the truth about the murderous exploitation that entangles them (and all of us). Bettis is interviewed by one of her playwriting professors at the Juilliard School about how and why she wrote this play.

MARSHA NORMAN: Hilary, I’m so happy to be able to talk to you about this play, which I love. When I first heard it at Juilliard, I just about fell out of my chair. It was so brave, it was so raw, it was so painful to listen to, and beautiful in its knowledge of the world. I think that you are able to depict violence toward women, and the violence women feel and experience in the world, better than anybody I know. Especially important is the fact that you do this in a way that enables us to continue watching. You know what I mean? I just think there’s lots of violence toward women depicted in the world, but yours comes from the heart of a woman who knows about this.

HILARY BETTIS: Aw, thanks, Marsh. It’s actually the first play I wrote at Juilliard.

This particular story seems to be set in a part of Mexico that you must have known. Is that so?

Yes and no. My grandfather and his family came from Monclova in the Caohuila state of Northern Mexico. They crossed the border and lived in El Paso, Texas, going to Juarez regularly—back then Juarez was a quiet town where American tourists often went for an afternoon. My grandfather saw a lot of violence and a lot of poverty, and really was incredibly, deeply tortured by it. It was always this elephant in the room that we never talked about growing up. He spoke fluent Spanish, but never in front of us. I think he was really afraid that we would be judged and held back by our Mexican heritage, like he was. Part of writing this play was like digging up my own family ghosts and things that I personally had always been afraid to talk about, because my family never talked about them. Also, because I’m Mexican and I’m white, I often struggle with wondering if I’m “allowed” to tell stories through this lens; growing up, the white kids always told me I was Latina or “ethnic,” and the Chicano kids always told me I was a “gringa,” so I never really felt like I fit in anywhere. So much of this play came out of wanting to really embrace this part of myself.

Did you talk with your family while you were writing this?

Not really. I sort of just vomited the play out. It was also coming out of learning about this horrific violence on the border—especially violence towards women, coined feminicidios. It haunted me. I wanted to understand what sort of circumstances in the world, in society, make women so disposable that it’s okay to use and brutalize them with impunity. (Poor men are brutalized, too, which I wanted to address in the play. The system is against all of them.) Where does this come from? My grandfather passed away, but I have since had conversations with my mother, my aunts, and my cousins, who still live in El Paso, about our family and the bigger social/political questions. I’m currently working on a family history project, and have reached out to cousins and aunts and uncles to really try to have more understanding about who we are. Writing this play gave me permission to do that.

What is your guess about why women are viewed as so disposable? I’ve done work on this topic in the rest of the world, and I’m wondering, why are women in such danger from men, and from other women who have adopted the values of the men? That’s why you wrote the play—you wanted people to know about this and you want it to stop. Is that correct?

Yeah, I mean, there is no one answer about why women are historically, across just about all of civilization, treated this way. It’s economics, it’s religion, it’s the reality of sex and pregnancy for women. It’s these value systems that get passed down from generation to generation that need questioning. I grew up in a really hyper-masculine world with a lot of brothers and no girls, and we lived in rural parts of America where all our neighbors had guns. Part of survival was learning how—at a very young age, without ever being aware of it—to navigate violence and men being tough. You did that by being able to take more pain than them, learning when to keep your mouth shut and when to stick up for yourself. And never showing your feelings or vulnerability. That’s definitely a recurring theme throughout my own life and my work. Women haven’t survived for eons by being “weak” and “emotional.” We’ve survived by being a hell of a lot tougher and braver than we’re given credit for, and I wanted to show that through Raquel’s journey in this play.

I think, also, there is so much dignity in these lives. I saw so much value and dignity in my own life and in the lives of women around me. What are the bigger forces that are keeping us silent? For me growing up, so much of that was religion. My dad is a pastor, and so church was a huge part of my own upbringing. My parents were always very loving and generous about religion, but we lived in very, very, very conservative communities where any questioning of faith meant certain ostracism. This play certainly tackles Catholicism in a big way, and religion in a big way.

These people, especially in the circumstances of this play, their lives are so utterly brutal, and everything they do and think is about survival. There’s no room or space for any sort of reflection, or judgment, or self-awareness. Those things are luxuries. So what do you do when you’re a woman who is starving and your children are starving? I think you grasp onto these, like, bigger mythologies to try to find some sort of meaning. At the same time these mythologies are telling you that you have to be submissive and pious, and you have this certain role in society, and if you don’t fill that there is no value to your life. In The Ghosts of Lote Bravo, Juanda is working in a sweatshop 15-hour days as a single mother of four. It’s nowhere near enough to feed her family. How do you even begin to think about pulling yourself out of that cycle when you don’t know how your children are going to eat tomorrow?

Tell me more about these sweatshops.

Absolutely. The maquilas on the border started during the Clinton era when NAFTA was passed. All of these big corporations were able to move their factories to the border so that they didn’t have to deal with labor or environmental laws, and didn’t have to pay taxes for moving goods into the United States. And because of the agriculture subsidization, 4.9 million family farmers were displaced. This is why so many people flocked to these factories, only to be paid slave wages, and flocked across our border. In the maquilas, women were hired over men—especially in textile factories—because they have smaller hands, are able to turn out more products, and are less likely to unionize or complain. Since there are no unions or labor laws, women are fired if they’re too old or if they get pregnant; some factories even force pregnancy tests. They’re literally working 12-hour, 15-hour shifts, six days a week, bringing home $30-35, and the inflation rate is the same as the United States. Imagine trying to go to the grocery store, and pay your rent in this country with $30 or $35 a week.

Because men have a harder time getting hired at these maquilas, coupled with the destruction NAFTA has caused to Mexico’s economy—not to mention the cartel turf wars and extortion that have forced many small family-owned businesses to close—poor men have little choice but to cross the U.S. border as migrants or work for the cartels. The men in this play are just as trapped as the women. It’s this bigger system that’s really keeping all of these people in their positions. It’s the same for men—they’re just as disposable, these young, poor boys.

I think this is a big part of why we have mass migration into the U.S., why people have no other choice but to cross the border. I wrote this play with an American audience in mind, because by the end of the play, I wanted an American audience to find themselves rooting for a Mexican immigrant to cross the border illegally. I wanted them to look at Juanda, Raquel, El Reloj, Pedro, Roberto, and see themselves, their children in these people. If you and your children were starving, if you saw violence and murder every single day, and just on the horizon is a safe country where people are allowed to dream, can make a decent living, of course you would cross the border. Any mother or father in their right mind would. We need to have compassion for this.

If you were going to try to fix the problem demonstrated in the play, what would you do?

Oh, God, I don’t even know where you start, honestly. I think first and foremost, I want us as a society to value these lives. I think if we can start valuing the lives of the poor and the exploited, then culturally we can no longer turn a blind eye.

How different is it on the border now from when you were a girl?

I mean, it’s become so much worse. When my mother was growing up they were able to go back and forth pretty freely—Juarez and Nogales, all these border towns, were really beautiful, safe, quiet cities that had a lot of small businesses, and people had a fairly decent life there. But besides NAFTA, it’s also our relentless addiction to drugs in this country, and the “war on drugs” started by the Reagan administration.

There are over 3,000 maquiladoras on the border today. And many of the drugs entering the U.S. are smuggled with trucks of goods produced in these factories. Think about it: Drugs are just as ubiquitous as Walmart goods. There’s no way that level of distribution happens by using people on foot crossing the desert. And the violence in 2018 is staggering. The border has become increasingly militarized with drones, assault weapons, many purchased by cartels in the U.S. at gun shows and pawn shops in the Southwest. (According to the ATF and U.S. Accountability Office, 70 percent of the guns they’ve traced in Mexico were purchased legally in the U.S.). Our country has been selling guns and making a profit off the horrific violence inflicted on the Mexican population by these cartels, and then we demonize desperate people for crossing the border? We paint them as evil so scared Americans run out and buy more guns…But this is a bigger conversation for another interview.

And it’s women who suffer most, because whenever things are bad women suffer the most.

Yeah. Amnesty International has estimated that 80 percent of migrant women are raped on their way to the U.S. In fact, many women take birth control before their journeys because they assume they’ll be raped. And then there’s sex trafficking, a booming industry for cartels. You can only sell drugs and guns once. You can sell the bodies of women and children over and over and over and over. And all that “free” internet porn? According to Rescue:Freedom, a nonprofit advocacy organization working to protect people from trafficking, 49 percent of the victims they’ve surveyed were forced to make porn. And one of the biggest U.S. hubs for cartel trafficking is in Corona, Queens. I know this will piss people off, but this is what I want people to have to think about when they watch porn. You’re getting off on a rape victim who might very well be murdered.

Tell me again why our popular culture is glorifying cartels?

One of the ironies about the suffering of women is that, yes, women get worse treatment, but they are more determined to survive, and this is why there are still people on the Earth. If it had just been men everybody would be gone. They would be dead. Because there are women, the societies have survived.

Yeah, absolutely. We fight the moment we’re born. Every woman I know is a fighter, a survivor.

But, I wonder, are there people working on this? I remember when I saw your play the first time I felt like something had to be done about this.

There are humanitarian organizations out there trying to help. No Más Muertes is one. They search the desert for migrants in need of help, no questions asked. And the Unitarian Church started the sanctuary movement by giving undocumented people safety from deportation in their churches. Rescue:Freedom is fighting against trafficking.

I will spend my entire life on this planet trying in every way I can fighting to bring attention to this. How can we call ourselves compassionate people when we allow such suffering to exist? We have a responsibility as storytellers to put narratives in the world that humanize and give dignity to these people. I’m so tired of women being objectified and flashy cartel shows portraying narco-culture as something to be glorified. This is part of the problem: If we think women enjoy being sexualized and drugs and guns are cool and all Mexicans are “bad guys,” then why change anything?

This is why it’s so imperative that women’s voices and the voices of people of color are being heard. I know there’s all the conversations in theatre and Hollywood about diversity, yada, yada, yada. I think to some extent it’s talking points for people to feel good about themselves. At the end of the day, the percentage of women with work being produced compared to men is astonishing…

Yeah, it’s 29 percent.

Until the world hears our voices, and values our voices, and respects our voices, then how will any of this stuff change? If theatres aren’t producing women equal to men, if TV shows aren’t producing stories about women that are written by women, letting women be at the helm of those stories, I don’t know how else that can start to change.

Well, men don’t think that our stories are worth telling, and when they do include women in their stories, they’re not generally recognizable as women, by and large. I think you could probably say that women may not represent men fairly either, but in that case we all ought to hear the stories of both of us, both men and women, and we have a lot of catching up to do about the stories of women.

We really do.

The language of the play is so beautiful, and the world is so gritty. How do you do that? How do you accomplish that from a craft standpoint?

I think it’s always this struggle of how do you, for an American audience, make a different culture authentic and give them dignity, but still write in a language that’s not their native language? I wanted The Ghosts of Lote Bravo to feel like it had been translated from Spanish to English, so I read Lorca plays, Neruda poems, Octavio Paz, and Carlos Fuentes translations. Because Spanish is just such a beautiful, poetic, lyrical language, translations of Spanish tend to feel a little bit more poetic. Even though in its native tongue it’s not heightened at all, in the translation it is.

But the trap of that, I’ve discovered—and I’ve had workshops of this play in the U.S. and Mexico, on the border, in middle America, New York, and L.A.—is that the tendency is to heighten the world, the acting, the visuals because of the lyrical language. It’s like all that classical stage Shakespeare training really gets in the way of authenticity. But that’s such a detriment to this play. The play needs to be brutal, and raw, and gritty, and ugly; all of the subtext that the actors play must be grounded in the circumstances of these people’s lives, and in the fear and the pain that these people are all in. The language is a counterpoint to that. But if you lean into the lyrical, and the poetry, and you try to make the design visually beautiful, we end up doing a grotesque disservice to who these people, the reality of their existence, and their dignity.

How does religion play in this world?

Religion is a recurring theme in a lot of things I write. Partly because I grew up with Christianity as a huge and influential part of my life. And my own struggle with religion.

What was that struggle, Hilary?

My life and childhood have been pretty hard. I saw and experienced physical and sexual violence. I was sexually abused at six, raped at 14—that’s how I lost my virginity. And I’ve seen a fair amount of gun violence. It just sort of came with the territory of rural and hunting communities. Almost everyone had a gun. When my brother and I were little kids, the husband of our babysitter beat her up and held us hostage in the basement with his shotgun. I have vague memories of hearing her screams while we were huddled in a closet. And in 8th grade, a boy who liked me and I only wanted to be friends with, showed up at my house one afternoon and said he had a present to give me and to close my eyes. When I opened them, he had a 45 pointed at my head and told me I “should be his girlfriend” or else. A few weeks later, his best friend beat me up in a field and sexually assaulted me. And all of this happened before high school. Things got much worse after high school and when I ran off to L.A., but those are stories for another day…

So all of this has happened to me—most of it I never told anyone, because I honestly and sincerely thought it was my fault for a very long time—and I’m going to these Evangelical youth groups with my friends, listening to the youth pastors beat us over the head about “purity” and saving ourselves for marriage. When I finally told an adult about being molested at six and that I was having suicidal thoughts, they told me—no joke—my negative feelings were because I “wasn’t praying hard enough to Jesus, and I needed to put him first in my life.” And then when I was 12 and had to put my dog Molly to sleep, who I had since I was born, another youth pastor told me animals have no souls and didn’t go to Heaven. I was like, “Fuck that! If my dog doesn’t go to Heaven then I’m done with this religion bullshit.”

So when the message you are constantly getting from adults as a little girl is like, “You have to stay pure, and your body and your sexuality is the only thing of value to you as a human being,” and you’re like, “Well, wait, these things have been taken from me.” So what does that mean? Does that mean that I’m trash because somebody raped me? What a horrible thing to say to little girls. But the thing is, so many women in our country grow up being taught only this. I mean, my best friend in middle school was pulled out of high school her freshmen year by her Evangelical parents because she started wearing makeup. She was homeschooled using the Bible, while her brother finished high school and went off to college, paid for by their parents.

For Juanda and Catholicism in this play, her survival, her ability to find meaning in the brutality she’s endured, stems from fighting to be a good Catholic. Trying to be pious and submissive, while trying to eat and feed her children. I think so many women have fallen into this. I think this is a big conversation in the United States between the coasts and Middle America. Juanda turns a blind eye to the reality of her daughter’s life because of her deep need to be submissive. And this makes her complacent in her daughter’s murder also. This is what Juanda has to come to terms with before she can really see and know her own child. For Raquel, living in this violence and choosing to be a prostitute of her own agency and pragmatism because it will feed her family—this idea of purity doesn’t fit into the reality of her life. And she sees value in herself that has nothing to do with her body. Her value comes from her courage, her dreams, her willingness to stand up for what she believes in. The play is really about a reckoning for Juanda.

And where does she get to in the end?

She has to look at her own belief system, which is also a cog in this big machine of oppression. She has to face how holding on to these dogmatic beliefs has cost her an honest and intimate relationship with her own daughter. Because so many people are trapped in such incomprehensible violence, and have no choice between violence and prostitution, how can you believe in Catholicism? I think that’s why so many people have embraced La Santa Muerte, because there is no judgment with her. Anybody can pray to her.

Tell me about La Santa Muerte.

Her origins date back to pre-Hispanic Mexico, but modern rituals also embrace some Catholicism.

So a native religion that was here before Catholicism came in and took over?

Yes.

So all you have to do is pray? Are there ceremonies, services?

It really depends on what you’re praying to her for. Love, protection, money, safety, survival, even revenge, all have different rituals. But you have to bring her offerings. You have to give something before you can ask for something in return, which I think is a really beautiful idea.

Can you mix and match? Take some Catholicism, some La Santa Muerte?

Yeah, and I think a lot of people in Mexico do. Both religions fill different voids for people. The Catholic Church has gone to great lengths to demonize La Santa Muerte and equate any worship of her to an act of evil. That’s why it’s taboo to openly worship La Santa Muerte in Mexico, yet there are shrines to her everywhere. When I was in Mexico City workshopping this play, I went to the original La Santa Muerte shrine in Teptio, a poor neighborhood of Mexico City that has a reputation for being dangerous. It’s become a site of pilgrimage now; people flock from all over the world to pay their respects to La Santa Muerte.

Hilary, where do you think this play fits in your body of work?

This play really cracks open two things I had sort of been dancing around as a writer. One is my own family background, and the other is unapologetically embracing what it means to be woman in a hyper-masculine world, because that’s who I am—that’s how I grew up.

And that’s where we are.

I think this play is really where I found my voice. I was afraid to write unapologetically from a woman’s perspective. In my early plays, I felt that I had to prove I can write men and masculine genres really well to be taken seriously. This play is a departure from that. Ironically, career-wise, this play is the play that got me my job on “The Americans,” and has gotten me commissions and TV development projects. As you always say, Marsha, “Write the things that scare you the most. That’s where your power is.”