Two years ago, John Mahoney called me to tell me he had cancer. It was a surprising call, less because of the news that he was ill—his health issues had been ongoing in the last several years—but more because it was such a rare moment of openness from one of the most private and humble people I’ve ever known. In our current climate of 24-hour self-obsession that has us documenting and sharing everything from our deepest secrets to what we ate for breakfast, John remained consistently above the fray, a model of fine manners and social restraint that was almost disorienting in its quaintness. This news was, he explained, something he was only sharing with me, and he asked if I would mind keeping it between us.

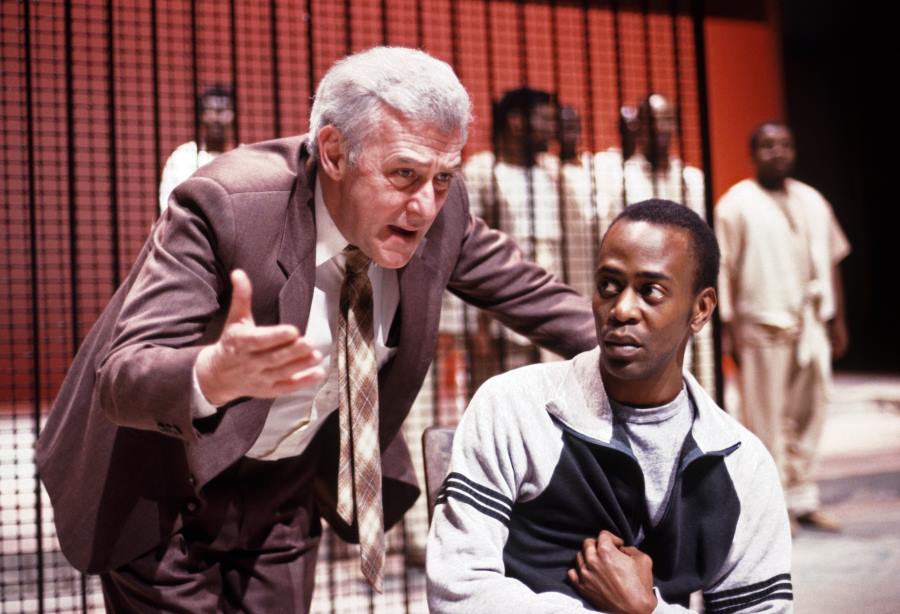

I was both honored and worried. I have loved John Mahoney since I was a very young woman, having seen him onstage for the first time when I was in high school and many, many times since. His performances in Orphans and You Can’t Take It With You at Steppenwolf Theatre were some of the most important and impactful audience experiences of my life. And directing him, which I was fortunate enough to do very early in my career, was an honor and a revelation.

We had become friends over the last 25 years, and I valued my time with him beyond measure. We both loved murder mysteries, great restaurants, and Lake Delavan in Wisconsin, where he and his longtime partner, Bernie, had a house. We talked about opera, the best place for steak, and performances we loved (and, yes, sometimes the ones we hated). But with this news about his health, our conversations turned to the big questions of life and death, of God and faith, of theatre and eternity. I was moved by his clarity and stunned by his honesty and, once again, changed by my life’s fortunate intersection with his. But even with all of this, the thought of losing him and the knowledge of his suffering was very, very difficult.

It would violate everything I know about John to share anything specific of those long and wonderful talks over the months of his treatment and recovery, but I can say that the John I had always known—elegant, chivalrous, well-raised—met his illness with those traits firmly in place and the self-same humility he brought to all of his fortunes, good and bad.

One day many years ago, we were walking through Galway, Ireland together. He could not take two steps without being stopped by adoring fans, most of whom were well-behaved, but many of whom were not, and he was as kind and patient with the former as with the latter. I found the walk exhausting, and when we finally got to lunch I asked him why he took that much time with everyone, even the people I considered unworthy of his goodwill. He said that he always thought of himself as a grateful child of God and he understood this to mean that in every interaction we have, it is our choice how we meet it, and he chose to meet his with the love and gratitude that he felt for God and that he knew God felt for him. He said he wasn’t always successful, but that was okay. He loved himself for trying. He did not share this to teach me—there was not even the subtlest hint that he felt it a lesson. He shared it because it was a choice he made that brought him joy and he wanted to share that joy.

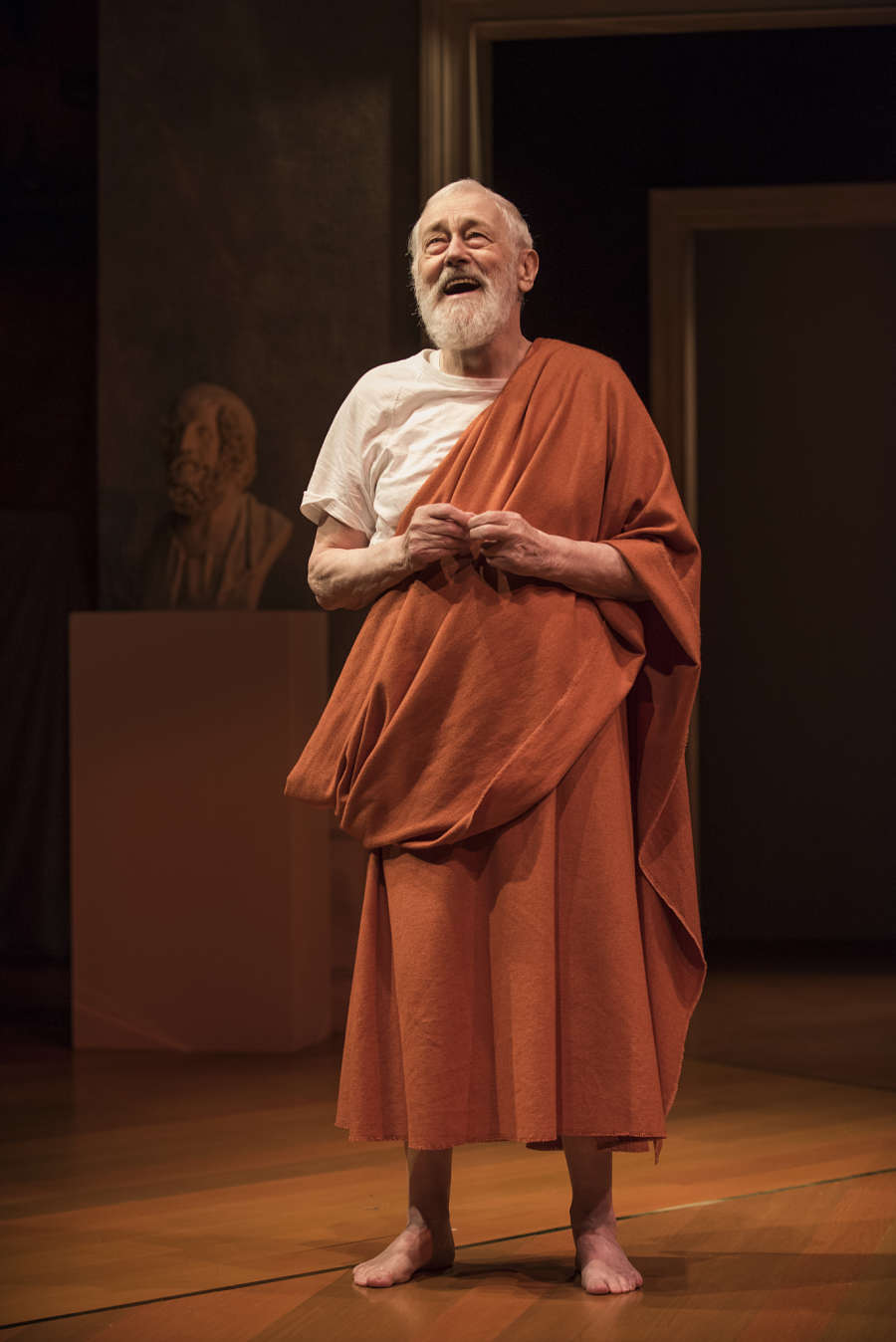

And that was what one always felt when John was onstage: his joy and what it gave him to share it. In his last role, he played the poet Homer contemplating whether his life’s work would ever amount to anything. Homer asks the audience not just if his work will have meaning, but if it will ever effect the choice of another—if it will, in fact, change the path of the receiver of that work in a way that makes them different people than they would have been without it.

John Mahoney was that rare actor whose presence onstage made you feel embraced and loved. He returned to the theatre again and again because the liveness of the exchange was one of the most rewarding feelings he could imagine. This deeply private and devout man spent years of his life in the most generous act of sharing there is—and he did it over and over and over until he simply could not do it anymore. Anyone who ever saw him knows what I’m talking about and shares with me the abiding sense that this interaction, whether on a street corner or a theatre, lovingly interrupted their day and made them feel, if not better, certainly different about how they themselves would treat their next encounter with another child of God.

In my last conversation with John before he went into the hospital for what was supposed to be a routine treatment, he asked me to promise that I wouldn’t give him a memorial if something happened to him. I laughed and said anyone who knew him even a little bit would know not to do such a thing, and why would he even bring that up? He said, “Well, you may never speak to me again.” And sadly, as in so many things, he was right. I have no doubt that John’s next journey will be made more beautiful by his work on earth and that this earth is a better place for having held him as long as it did.