In the wake of a horrific act of violence at a pop concert in Manchester, England, the thoughts of Sarah Frankcom, artistic director of Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theatre, turned to Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, which she staged as a vehicle for gathering and healing her community. This slice of Americana, according to a New York Times article that marked the production’s September opening, is not well known in the U.K.

When Scarlett Johansson sought to raise funds to support the reconstruction of Puerto Rico, in the wake of natural disaster, she conscripted her castmates from The Avengers films to perform in a one-night reading of Our Town. Given the international popularity of their films, Johansson, Robert Downey Jr., Chris Evans, and Mark Ruffalo appearing live would have sold copious tickets for a reading of pretty much anything they wanted. But Johansson gave them Grover’s Corners.

Early in the 2017-18 theatrical season, the first that was capable of fully addressing the political divisiveness and roiling anger felt by many in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, professional theatres in Maryland, Florida, and California (surely just three among others) opted to retell the story of Our Town through the vehicles of, respectively, puppetry; a multilingual mélange of English, Spanish and Creole; and American Sign Language.

At a time of stress, a time of fear, a time of sorrow, it seems that many theatremakers have independently and almost simultaneously turned to a play that turns 80 years old today (its premiere was at New Jersey’s McCarter Theatre on this day in 1938), a Pulitzer Prize winner of seemingly bygone days, capturing the lives and deaths in a white New Hampshire village at the turn of the 20th century. What could be, at least on its surface, more anachronistic and less representative of the world today, more ill-suited to speak to modern concerns?

Of course, Our Town is hardly scarce on U.S. stages. But it is often denigrated as “a high school play” because of its frequent mountings in academic auditoriums. As of this writing, licensing house Samuel French lists 69 upcoming productions this year, and indeed high schools do dominate that accounting. But if we use the common journalistic metric of two is a coincidence and three is a trend, then five professional productions in a short span this past autumn might be viewed as a groundswell—an indication that there is something about Our Town that makes it a perennial apt for this particular moment. It’s not just the freedom to stage it with a bare minimum of props and an easily expanded cast, which surely appeals to school and community groups.

Oddly, for a play that we are told is so specifically set in a particular time and place, it may well be the work’s adaptability that serves it so well. It broke creative ground for its lack of scenery back in 1938, and that certainly set a template. That may be why, unlike many classics, it has not been locked into a singular visual or verbal approach, trapped within the confines of the original production. It also doesn’t hurt that Wilder’s nephew Tappan, who administers his uncle’s estate, has endeavored to keep the work a living text, rather than a museum piece, seemingly echoing his uncle’s own preferences.

While the Miami New Drama production last fall invited Nilo Cruz to provide Spanish translations and Jeff Augustin to provide the Creole, productions decades earlier had rendered the play in other languages for other countries; a Spanish production was seen in Puerto Rico at least as early as 1961, if not before. The Deaf West Theatre production at Pasadena Playhouse employed that company’s signature style of blending performances in ASL and English (it is important to remember the ASL is a language of its own, not simply a physical and visual representation of English).

David Cromer’s celebrated production, which began with the Chicago troupe the Hypocrites, upended any assumptions of fidelity to the 1938 staging, with a scenic reveal that was heartstopping in its beauty, sadness, and sheer surprise. Cromer’s interpretation, by virtue of a solid Off-Broadway run and restagings in other cities, also showed that productions need not be constrained by the original genders of the characters, with Helen Hunt taking on the iconic Stage Manager role at one point, prefiguring Jane Kaczmarek’s performance this fall with Deaf West. But Hunt and Kaczmarek were hardly the first female Stage Managers: Geraldine Fitzgerald played the role in the 1970s at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, according to Rosey Strub at the Wilder Family LLC.

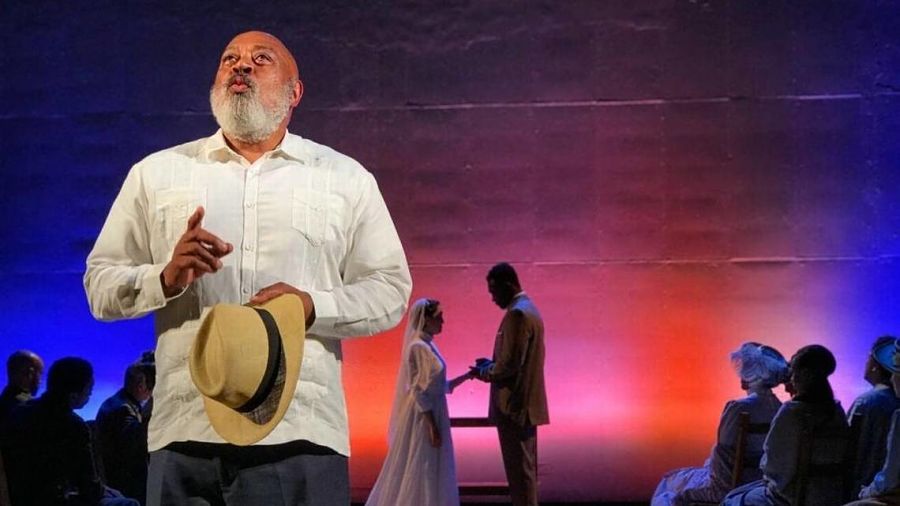

At the Olney Theatre Center in Maryland, Aaron Posner shaved the acting company, which numbered 50 in the original Broadway production, down to just seven—but they gave life to Grover’s Corners through a complement of puppets. At Miami New Drama, Keith Randolph Smith, a veteran of plays by August Wilson, led a multicultural cast in the trilingual production; a 1968 production at the Inner City Cultural Center in Los Angeles had boasted a fully integrated cast of black, Asian, Latinx and white actors, garnering the cross-continental attention of The New York Times.

The play’s persistence over eight decades, and its relative prominence this past fall, may ultimately have less to do with its versatility as a vehicle for cultural creativity than with Wilder’s underlying impulses. Looking beyond the particulars of Grover’s Corners, N.H., and even the United States, Our Town is a work of existentialism, constantly reminding us of the inevitability of lives passing away all too fleetingly, and that we must take our pleasures and joys in the everyday even as we come to understand how brief and indeed insignificant our existence is in the face of the vast universe and the infinity of time. As his major stage works predated those of Samuel Beckett, it is not entirely surprising to discover that Wilder once undertook to explain Waiting for Godot to the director Alan Schneider before the latter met Beckett.

The first two acts of Our Town may seem little more than a quaint vision of early 20th-century small-town life, domesticity, and romance, but it is hardly an unblemished, fully idealized portrait. Take note of characters mentioned who have died or will die, of the underprivileged elsewhere in the town (unseen), of the troubled alcoholic choir director Simon Stimson. Wilder may be primarily lulling us into comfort, but want and mortality are ever-present.

When Act 3 turns to give voice to the dead themselves, tut-tutting over how little they knew when alive and how much time they wasted with petty concerns, time that could have been better spent, Our Town—while still genteel in its telling, perhaps even a bit detached—becomes universal and transcendental. In the Manchester production, the actor playing the Stage Manager was Muslim, and the play’s heart-wrenching flashback invokes a birthday breakfast treat of bacon, forbidden in both Islam and Judaism. But that detail is irrelevant in the greater construct—just one example for one character and one actor in one locale for a play that had already moved beyond the laws and limits of earthbound life.

In some ways, Our Town may seem a peculiar choice for high schools, since its greatest insights are about the brevity of our time on earth, our losses, and our mortality. No doubt George and Emily’s romance is particular affecting in such productions, but unless the young actors have already lost loved ones, can they fully appreciate and enact the agonizing third act? Lives seem so endless in our youth. Our Town might be uniquely well suited to be played by a cast of seniors, who can look back on their own lives as they contemplate their not-so-distant, everlasting futures in the cemetery on the hill, even as they can recall their own youths in inevitably simpler times, and their own loves.

On the other hand, at a time when young people are filled with anxieties about the future—who they will be, who they might love, what does life hold in store—there is something to be said for having them enact a story in which they grapple not only with first love, but also with the possibility of death, tempered with a poignant depiction of why every moment in life, even the simplest, is to be experienced with profound appreciation for every little detail.

For those of any age, now daily facing what so many view as assaults on the very principles of American life, perhaps there is comfort in Our Town. But there are also ever-present threats and inequities in the account willed to us by Thornton Wilder. Being reminded of those as well should spur us to make a difference while we can, while we still have time left—before, as the Stage Manager says of the lingering dead, “the earth part of [us] burns away.”