In Dakar, Senegal, the general refrain is that theatre “doesn’t exist” in the nation’s capital city, the westernmost spot on the continent. Since the heyday of African theatre in the 1990s, as countries declared their independence from their historic colonizers and reclaimed their native theatrical traditions, creating festivals and building a proud pan-African audience, the momentum has largely dissipated in West Africa.

But some individuals are still doggedly pursuing theatre where and how they can. Since 2014, Sahite Sarr Samb has been the general director of Sorano Theater, sub-Saharan Africa’s first black theatre, founded as part of the First World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar in 1966. Samb remembers a vital relationship between education and culture, including theatre, when he was a schoolboy in the 1960s. With the modernization and globalization of the 1980s and 1990s, he watched cultural priorities shift in Senegal, and the theatre scene subsequently struggle to keep up with the changing world.

So Sorano Theater no longer enjoys the prosperity nor the prestige it once did. Government support—not only fiscal but also cultural—has greatly diminished since the theatre’s founding. What’s more, the National Acting Conservatory stopped accepting students from 1980 to 1990, graduating its next class in 1994. For Sorano Theater, this froze the hiring pool of trained professional performers from which they could construct their national company for more than a decade. In the years since, Samb feels that public schools have become increasingly less open to cultural education. In response, one of his initiatives at Sorano Theater is to present performances on Wednesdays for school groups, to work on cultivating students as young audiences.

Samb sees the Sorano Theater’s current mission as trifold: as a monument to black culture, paying tribute to its historical heritage; as a vehicle for the promotion of Senegalese and, more broadly, African culture; and as a place for artistic experimentation. Samb explains, “Theatre has always existed in Africa, with our tradition of griots, who would conduct elaborate storytelling through a mix of songs, dance, music, narrative, and historical references. The proscenium stage, and its European influence, greatly changed the perception of theatre here in Senegal, and who feels welcome in the room.”

Sorano Theater has three official companies, each with a specific audience: the “traditional” ensemble, which attracts a general audience with its musical performances; the dance company, which honors traditional forms of Senegalese dance and music, both at home and touring abroad; and the dramatic company, which presents works in French and Wolof, both historic and contemporary. This season, the dramatic company will remount its new adaptation of Othello by Pathé Diagne in Wolof.

For the first several decades after independence, French-language theatre here tended to comprise history plays dealing with social mores and political satire. Senegalese still speak reverentially about the 1966 presentation of Aimé Césaire’s La Tragédie du Roi Christophe, starring Douta Seck. Senegalese audiences were hungry for stories that explored the issue of independence, and were looking for guidance from other cultures’ examples. During the renaissance of African theatre in the 1990s, the tradition bifurcated into general-audience shows in local languages and Western-style performances in French. Currently, theatre in local languages, primarily Wolof, is largely found in serialized television dramas. People call these TV shows “theatre,” not making a distinction between what they can watch from the comfort of their own living room and what they would pay to see in a public setting.

Looking ahead, Samb believes that Sorano will only survive in collaboration with theatres abroad, including sending the company’s shows on tour and sending its performers to train at schools around the world, enlarging their perspectives and fostering intercultural dialogue. Says Samb, “We need to be really open and find a new identity, because the Senegalese people have different needs than those that they had when we opened in 1966.”

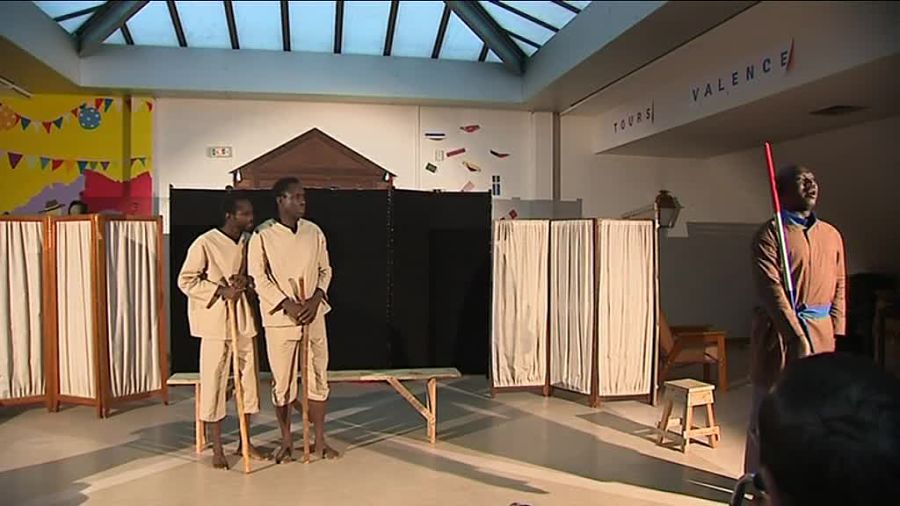

To that end, Sorano toured a production of Le Chemin des Tirailleurs to a small town in France in fall 2017, with a cast made up of four Senegalese and two French actors.

Samb explains that there are currently three types of theatre in Senegal: non-professional companies serving general audiences, Sorano’s government-funded professional company, and semi-professional private companies. The lack of state funding opportunities, heavy taxes, and an absence of small and midsize theatre spaces and professional theatre personnel spell doom for most independent professional companies.

This was not always the case. Marième Faye, an acclaimed Senegalese actress, recalls that when she founded the company Côté Jardin with Patricia Gomis in 1994, there were several small, independent theatre companies cropping up at the same time. But there was less a feeling of community among them than of competition for limited resources and audiences, which eventually led to most of the companies’ demise. Says Faye, “Every other West African country has surpassed Senegal in terms of their theatre community by now, because our theatre is not financially supported by the state. Money is too hard to come by here.” She says she dreams of having a small, private theatre in Dakar at her disposal, with 100-200 seats, as she believes it would be easier to sell for a long run, and easier to build community.

Despite these obstacles, Faye has found professional success, particularly with her most recent show, Polymachin, which attracted all types of audiences, even people who don’t regularly go to the theatre because they feel it isn’t “for” them. Everyone from the woman who sells peanuts on the corner to the nation’s ambassador came to see the show, she says, because it spoke openly and humorously about a shared cultural Senegalese experience: polygamy.

Faye’s style is very physical, drawing from clown and burlesque training, which differs greatly from the formal, classical French training that actors receive at Senegal’s National Conservatory. Her newest project is a circus park for kids, located in Park Hann on the outskirts of Dakar.

For her part, Gomis went on to create a circus and theatre school, Association Djarama, located in the village of Toubab Dialaw, about an hour outside of Dakar, which is also the village where Germaine Acogny’s Ecole des Sables dance school and Gérard Chenet’s Sobo Badé cultural center are located.

And then there is Kàddu Yaarax (“Voice of the Yarakh neighborhood”), a small company founded in 1994, which has been producing an international festival every July for the past 13 years. Although the Kàddu Yaarax company draws its inspiration most directly from Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed model, there is a long tradition of “development theatre” in Africa, tracing back to Botswana in 1974. “Development theatre” is topical, socially provocative, and often used for educational purposes, playing the role of mass media in villages without TV.

Diol Mamadou’s troupe comprises about 30 people, a mix of men and women. Mamadou says they meet after work and rehearse every day, 12 months a year. Although Mamadou is the artistic director, all the company’s plays are the result of collective creation, with collaboration every step of the way. When they tackle a new topic—recent works have touched on water scarcity and climate change, the changing lives of traditional shepherds, and currency and redistribution of wealth in Senegal—they improvise scenes for several days, based on their own experience and imagination. From this improvisation, they pick out their favorite scenes and create a script.

It goes without saying that Kàddu Yaarax’s work is performed exclusively in local languages rather than French. The company’s work provokes audience members to action and conversation—sometimes even heated arguments.

According to Mamadou, their troupe’s work liberates them from colonial structures and conceptions of theatre, even if it prevents them from being considered by some as “true” theatre. Kàddu Yaraax has never received state funding, because national organizations brand their work as “activism” and see it as oppositional to the state. This attitude used to be more prevalent, since artists were usually at the forefront of those fighting for freedom, justice, and human rights, so politicians made little distinction between actors and political dissidents. But Mamadou sees their work as part of a long African theatrical tradition. There are no barriers with this form of theatre; it is for everyone. The troupe literally brings theatre to the people, touring shows to villages that have never even heard of the concept of theatre, let alone their style of “theatre forum.”

Meanwhile, in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, just over 3,000 miles southeast, the cultural sector is still struggling to find its footing since the conclusion of the most recent civil war in 2011. Ivorians are quick to acknowledge their rich theatrical tradition, and there is certainly no shortage of artists. But here as well, theatre companies and artists are sorely lacking government support, especially of the financial kind.

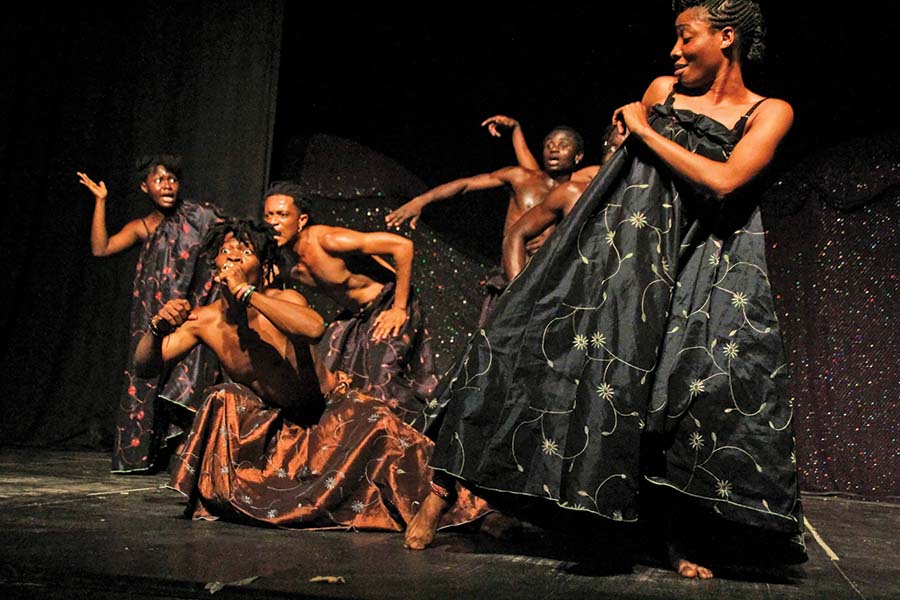

Yet institutions of theatrical training persist, including the National Superior Institute for Arts and Cultural Action (INSAAC), as well as private centers such as the Marie-Rose Guiraud School of Dance and Cultural Exchange and Werewere Liking’s Village KiYi Mbock. Liking founded this last company (whose name means “ultimate universal knowledge” in Bassa, Liking’s mother tongue) in 1985, and has offered free education in traditional pan-African theatre practices to hundreds of young people ever since.

The KiYi company performed three times in October 2017 (down from their boom years, when they performed every night, Tuesday-Saturday): once in their own black-box theatre, once at the luxury hotel, Hotel Ivoire, and once at the Academy of Sciences, Arts and African and African Diaspora Cultures. The first performance was part of a celebratory evening, thanking the Ivorian Minister of Culture and Francophone Countries and other invited prestigious guests for their support—which incidentally gave the minister the occasion to promise a new legal status for the Village KiYi, and hence governmental financial support for years to come.

The other two performances were brief excerpts of longer works, over in the blink of an eye. At the Academy, the “dressing room” offered to the performers was the fire escape stairway just behind the stage. Hours of rigorous training and rehearsal went into each and every second of those performances. And yet, for audience members, they were presented as local flavor, a splash of African dance and drumming, without time taken to contextualize the different cultures or traditions represented.

As an American audience member attending theatre in these nations’ capitals, I was at first surprised by the way that Western theatre conventions were completely disregarded: Performances started at least half an hour late, as a rule; audience members continued to trickle in for at least an hour after the performance started, and would then unabashedly not only text or check their emails, but also receive phone calls during performances, without leaving their seats. Photographers hired to document the event had extraordinarily bright flashbulbs that they would train on the audience and the performers in equal measure, blinding everyone. Audience members would film entire performances on their cell phones, akin to concert attendees in the United States. And on and on.

But it soon dawned on me that of course West African audiences haven’t been trained in the same routines of theatregoing as American or European audiences. This behavior didn’t bespeak an intentional lack of respect for the performers, but rather a different cultural approach to attending a theatrical occurrence. Their traditional vision of an audience member does not necessarily involve silence and stillness, but rather a vocal and often even physical engagement (or disengagement, as the case may be) with the action onstage.

It comes as no surprise that one of the biggest challenging facing West African theatre is the lasting aesthetic legacy of colonialism, with the proscenium stage physically reshaping the way oral storytelling is conveyed. Stories that were once told outside, in relationship to the natural world and accessible to every member of a community who cared to attend, can feel hopelessly boxed in by the confines of a proscenium stage. What’s more, if the West African public doesn’t feel at home in a European theatre, or doesn’t see the value in paying to attend theatre presented on a proscenium stage, who exactly is the intended audience for shows presented in this context?

Moreover, when it comes to the role of the arts in these two West African countries, what kind of irrational optimism does it take to choose art over more practical ways of earning a living? Is it a means of bowing out, or conversely of engaging on a more ideological scale? When your future is already so economically uncertain, is it easier to follow your passion, at the neglect of all else? Without the commercial pressure and potential driving the theatre scene in Western capital cities, what makes these impoverished artists stick with it?

For the Village KiYi, the prospect of getting youth off the streets and training them in the arts to foment social change isn’t an empty one; it’s vital, particularly when the daily reality is so much more dire.

Watching that first KiYi performance for the Minister of Culture, the expression joie de vivre sprang to mind. In Côte d’Ivoire, it’s not just an expression of someone who knows how to enjoy life, but an expression of gratitude for having your life to live, against all odds. When you know how precarious life is, you treat it with more value. When you know how hard it can be, you’re more apt to find lightness and humor within. And when your whole world is the Village KiYi, you have no choice but to dance as if your life depends on it, because to some extent it does.

Amelia Parenteau is a freelance cultural journalist, playwright, and French translator. Upcoming: America is Hard to See from New York City-based Life Jacket Theatre Company (HERE, Jan. 30-Feb. 24). She has been published in HowlRound, Culturebot, and Extended Play, among others.