Longtime director Susan H. Schulman recently told me a revealing anecdote about her parents.

“They went to see the first show I directed Off-Broadway, all the way down in the Bowery,” Schulman recalled. “They were very excited to come, and they schlepped down to watch this little show. And at the intermission, my father said: ‘It’s wonderful, we love it, we love it! Now, tell me honey—what did you do?’”

The paradox of the theatre director is that your work is evident everywhere, and also nowhere.

In that sense, the field has not changed much. Theatre directing is still not for the faint of heart: It involves a passion and aptitude for visual and textual storytelling. It requires knowledge of every element of a production, from acting to technical design. Most of all, it calls for an ability to understand people and get them to help you articulate your vision. As Anne Bogart has written in A Director Prepares, “I work in the theatre because I want the challenge of decisiveness and articulation in my daily life. Directing chose me as much as I chose it.”

If the job description and skill set of directing hasn’t changed much, the circumstances in which American directors work certainly has. The cost of renting performance spaces has shot up in major urban areas, and the existence of affordable spaces for young artists everywhere has dwindled. While programs and grants to nurture young playwrights have sprung up across the country, support for those with directorial aspirations is relatively sparse. Still, while many of today’s younger directors receive formal training in the craft, including at MFA programs, many of the field’s veteran directors—many of who now teach directing at said programs—had few such options available in their time. What do they teach, then?

“I can’t teach you talent,” insists Schulman, head of the graduate program in directing for musical theatre at Penn State University. “I can’t teach you insight, and sensitivity, and awareness, and perception. I can’t teach you poetry—but I can help you expand these skills by asking the right questions.”

Schulman is quick to emphasize that there are those who don’t believe that any elements of craft should be taught in a classroom. “I am not as self-righteous as I used to be about things. I don’t have all the answers, but everybody who graduates from my program will be able to put a show on, and it will make sense.”

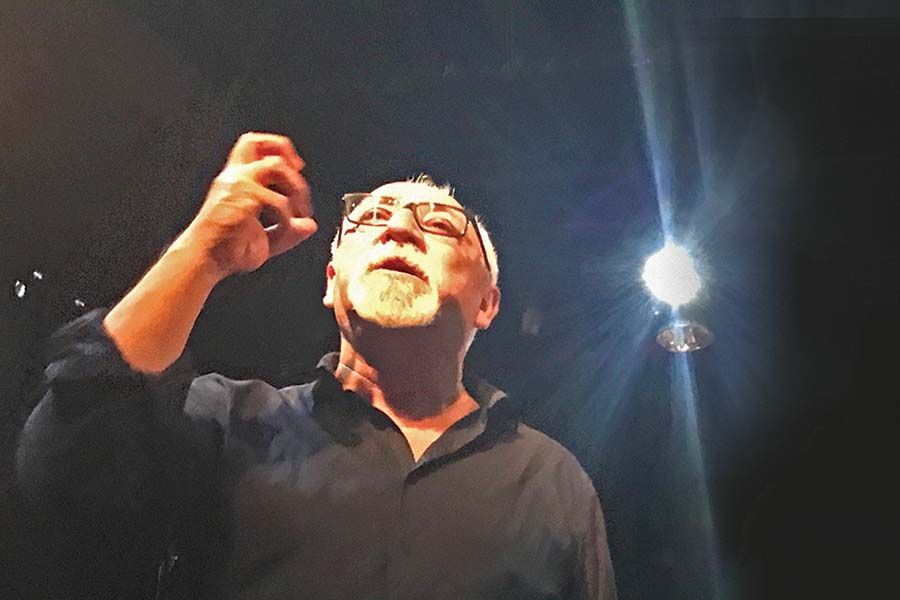

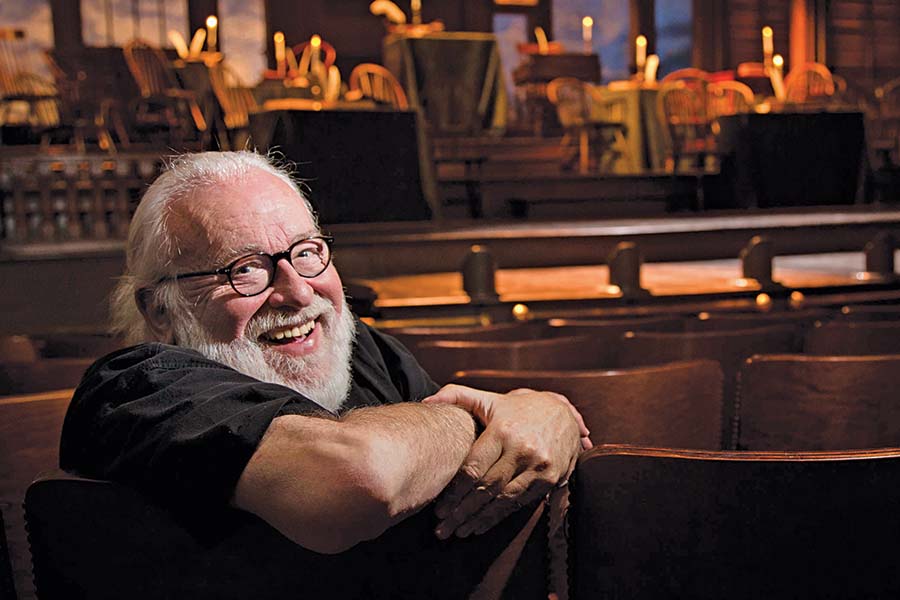

Frank Galati, the master director who cut his teeth at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company and taught at Northwestern University for more than three decades, will tell you that an MFA has plenty to offer young directors, even though he got his start without one (his Ph.D. is in performance studies).

“Certain aspects of the job can most definitely be taught, the way a language can be taught—the grammar, the practice. Those are rules that don’t really change,” Galati explains. “Vocal technique, versification—there’s an infinite number of these technical and poetic techniques that can be taught and can be learned.”

Schulman also has grounding in academia: Her MFA is in playwriting from Yale, where the program’s conservatory structure meant she had plenty of access to classes on directing, acting, and design. For his part, in addition to his Ph.D., Galati has pursued his directing career while concurrently teaching and researching at Northwestern.

Seret Scott’s career took a different path. A young actress deeply involved in the Civil Rights Movement, women’s liberation, and the protests of the Vietnam era, she left her studies at NYU’s theatre program (which would later become Tisch School of the Arts) to work with the itinerant New Orleans-based Free Southern Theatre, performing for poor communities in the rural South. Leaving NYU meant her scholarship would be pulled, but Scott felt compelled to partake in the movement, especially after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. She would go on to have a distinguished acting career before switching to directing, and decades of fruitful work ensued.

Scott was recently at the Sundance Institute in Arles, France, taking advantage of this unique director-centered residency to interact with fellow directors JoAnne Akalaitis, Diane Rodriguez, Ali Chahrour, and Daniel Aukin.

“You definitely learn things by working, but there are things you learn by going to school as well—like avoiding rookie mistakes, and how to incorporate the design process into whatever you are doing,” Scott proposes.

Describing her first professional production, Scott laughs ruefully. “Three months in advance, I was getting designs from the costume and set designer. I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ As an actor I walk onto that stage, and my work is already done. As a director, I had to begin to think about what I wanted to say far, far in advance.

“It was a new way of thinking,” she continues. “Being able to understand the largeness and value of advance preparation actually takes a huge weight off your shoulders—knowing you have things in some sort of order, just as you want them, even before casting. School can help with that.”

Whether they had a graduate degree or not, all the veteran directors I spoke with for this article emphasized the importance of mentorship. José Luis Valenzuela, founder of the Latino Theatre Company and tenured theatre professor at UCLA, warmly described how he met his mentor, Stein Winge.

“He was coming from Norway to direct a play at the Los Angeles Theatre Center—Three Sisters or Barabbas, one of the two. I was already directing, and I insisted on spending time with him. He’d never seen a Mexican in his life! But I kept insisting, and he said, ‘Okay, you can come into my rehearsal room.’”

Winge became Valenzuela’s mentor for the next nine years. “I followed him all over the world to see how he created his way of directing, how he talked to the designers. We did most of the Shakespeares and Ibsens and Chekhovs. He directed opera in Europe. It was amazing training. He’s still my mentor!”

These days, organizations like the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC) provide budding directors opportunities their forebears weren’t always privy to. “We now have outlets for young emerging directors that didn’t exist,” Schulman observes. “SDC does a great job with internships, observerships, and getting young directors in contact with master directors, to observe and do work in regional theatres and on Broadway. There was no outlet like that for me once I left school.”

But mentorship can often start earlier than college graduation. Galati fondly remembers Ralph Lane, a high school drama teacher who encouraged him to direct his first production at the ripe age of 15. Lane went on to teach the likes of Laurie Metcalf, John Malkovich, and other Steppenwolf founders at Illinois State University.

Laird Williamson, who has worked for major regional theatres from coast to coast, including the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and D.C.’s Shakespeare Theatre Company, recalls summers at a theatre camp in Eagles Mere, Pa., where he was taught by the late, great Alvina Krause. “She really changed my life,” Williamson recalls. “She made me discover who I was, and got me deeply involved in working closely with actors.”

In graduate school at the University of Texas-Austin, Williamson found further mentorship in his relationship with Francis Hodge, a legendary drama professor who wrote the seminal text Play Directing: Analysis, Communication, and Style. “He was a kind of nuts-and-bolts, objective, very action-verb-oriented person,” Williamson recalls. “Getting impressions and delving into plays was what I working on, and Hodge helped me nail things down more.”

Young directors may have more access to mentorship than ever before, but they currently face higher barriers to entry than their predecessors: It isn’t just more expensive to get trained, it’s more expensive to stage the work that will get them noticed.

“It’s not who you know, it’s who knows your work,” Williamson emphasizes. “In my career, people had known me and seen my work as an actor. One thing led to another, and I was fortunate enough to find work that gained me exposure. It’s a big part of the battle.

“There’s a lesson there,” he continues. “If it’s there, and you have the opportunity, do it! It doesn’t matter where you are—people will see your work and take notice.”

Even if available abandoned warehouses and basements are fewer and farther between, and rents for performance spaces have never been higher, directors continue to find places to stage plays and performances with scrappy collectives. But how do they make the next step to working with more established small theatres? Institutions took bigger risks when she was starting out, Schulman acknowledges. “The smaller theatre companies of New York would hire somebody like me, who was young and inexperienced,” she says. “Now they hire somebody like me, who is established. I was hired by Playwrights Horizons fresh out of grad school—that would rarely happen now.”

Another pressure Schulman’s generation largely avoided: today’s crushing student debt. “I can’t imagine what it would have been like for me if I had left grad school with debt,” Schulman concedes.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. Young directors have some advantages in the age of shareable social media.

“Now a director can put something up for a single performance and tape it, so somebody somewhere sees their work,” Scott says. “It’s not that they want to get into TV or film—it’s just that today there are tools to enable people who count to see what they’ve done. We didn’t have that. If a person didn’t walk into the room where you were doing the work, they didn’t know you.”

But new technology is a double-edged sword. We live in one of the most distractible and disruptive periods of technological advancement, and young artists now face audiences whose attention span may have significantly shrunk. Galati, for one, feels that the prominence of television and the way it molds audiences has seeped into the aesthetics of contemporary playwriting and directorial staging.

“The short attention span that television demands, the constant grabbing for attention—Stay with me! Stay with me! Here’s a surprise, here’s a joke!—can be detrimental to theatre when the art form begins to compete by seizing the audience with every conceivable means.”

If theatre aesthetics are evolving along with the tech that supports them, the impetus to respond to contemporary concerns remains as vital as ever. The canard that the current generation is complacent, spoiled, and comfortable is contradicted by a wave of increasingly passionate responses by young artists to horrific new realities on the horizon: the seemingly unhindered rise of white nationalism, the implacable advancement of climate change, a political system that seems to lose meaning and contact with reality daily.

It’s a trend their mentors have noticed and are encouraging. Insists Valenzuela, “The role theatre plays in society today is not entertainment! It contains forms of entertainment, but that’s not the main idea. I want to be reignited and re-inspired by theatre. Artists are intellectuals who look at the world and try to redefine it for themselves and for others, by giving joy, beauty, and critical thinking.”

Thanks in part to Valenzuela’s efforts, last November LATC hosted Encuentro de las Americas, a three-week-long festival of theatre and culture by companies from the U.S. and Latin America. The first Encuentro, in 2014, was born out of Valenzuela’s observation that not enough people were talking about—or even knew about—the vibrant Latinx theatre being produced around the country.

Barriers to access in the world of professional theatre due to race or gender seem to have shrunk somewhat, but women and people of color still contend with preconceived ideas of what work they may be drawn to. Directors like Scott and Valenzuela show no signs of resting on their laurels.

“Theatre has a role to play in every community and every society all over the world,” Valenzuela declares. “The best theatre happens when political turmoil is happening. I expect young directors to come up right now and do the most amazing work.”

What other advice do these veterans have for their students and successors?

“Experience as much art as you possibly can,” Schulman urges. “Go to museums, dance concerts, productions by small theatre companies, concerts—this can be expensive, but there are also a lot of low-cost or free possibilities. And, secondly—work! Practice is so important. If nobody will give you the opportunity, make it for yourself. I never would’ve had a career if I had waited for somebody to give me a job. It all came about because my friends and I got together and put on a play.”

“It is paramount,” Scott advises, “for young directors to work in as many kinds of theatres as possible. Often writers, producers, and other collaborators attend shows in smaller venues searching for up-and-coming artists and projects that speak to their interests. Don’t wait for perfect circumstances.”

Williamson strikes a similar note. “Do whatever work is out there—just start doing it. You may have to turn some things down, but just keep expanding your territory. Acting is the core of what you are doing—honor the actor’s craft while you are trying to do everything else.”

Valenzuela adds an exhortation for young artists: “Art is revolutionary. Artists are provocateurs. You don’t have to do agitprop—we can express things in different ways. Please, young directors, let’s begin a process of rebuilding the American theatre! Giving compassion in these times is important.”

“Read,” Galati advises. “Read. Read. Read. The limitless well of nourishment and intellectual stimulation and the secrets and mysteries in the millions of books that have been concocted and sent out into the world—these have to be read, and reread. Working in the theatre, you get to return to the text day after day after day—as it gets into your bones, you become enlarged, strengthened, fueled. Find somebody at whose feet you want to sit, and try to absorb. Be modest. And don’t talk so much.”

Fabiana Cabral is a writer and editor based in Boston.