Performer, director, and administrator Alan Mandell’s theatre roots run deep, starting with an appearance in an adaptation of Oliver Twist during his childhood in Toronto in the 1930s. He would serve as business manager of the influential Actor’s Workshop in San Francisco—whose seminal prison staging of Waiting for Godot marked its 60th anniversary in November—and general manager of that company’s New York successor, the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center. He would go on to co-found the San Quentin Drama Workshop, and later work with Beckett and tour the writer’s plays throughout Europe.

Since the 1970s, when Mandell moved to Los Angeles for opportunities onscreen, he’s been a staple of the L.A. theatre scene, including projects with organizations such as Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, Actor’s Theatre Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Theatre Center, and Center Theatre Group.

In August I spoke with Mandell, who turns 90 today (and who celebrated this milestone by performing a tap routine with his teenage granddaughter), about his storied stage career.

RUSSELL M. DEMBIN: You’ve done stage work for several decades, though you’ve mentioned that your theatre days are behind you. What would bring you back?

ALAN MANDELL: I’m still interested in doing things that are challenging, although at this point, as I’ve said—and I don’t think people believe me—I don’t want to do any more plays here in L.A. I mean there’s only one other play I want to do, and I’m in touch with the writer on that, and that depends on a meeting that I have coming up for a TV series, which is very special if it happens.

I was sent the script that someone commissioned the writer Will Manus to do on Sir John Gielgud. As I said to him, “If you had sent this to me when I was 85, I might have said yes.” I’m going to be 90 this year, which is fine—I mean, my memory is still great, and so thank God—but at this stage I just don’t want to do another play. It’s too much work. I’m very interested in doing film and television, which also can be challenging if you do the right things.

Going back to the beginning of your career in the States, could you talk about your first visit to San Francisco and how you got involved with the Actor’s Workshop?

I was running a theatre in Toronto, and working at a full-time job, so I was just exhausted and needed to get away, so I went to San Francisco. My older sister was living there, she and her husband, and her two children. And so she said, “Why don’t you come out for a week?” So I did. It was in the middle of winter in Toronto, which was really rather fierce. I recall asking my sister if there was someplace where they had perhaps a workshop where you could go and work on scenes, or a play, or something. And she said she knew of an actor’s workshop, and she said she would drive me down there.

I walked in. It was a reconverted garage, and that was the San Francisco Actor’s Workshop. As I walked in there was nobody there—I mean, the door was open, and I just walked in, and I kept shouting, “Hello, hello.” Nobody answered. The phone was ringing. I thought that was odd that there was nobody there to pick up the phone. I wandered throughout the place. There was a theatre there, separated by the office, which is where I was. As the phone rang, out of habit I just picked up the phone and said hello. And they said, “Is this the Actor’s Workshop?” I said yes. They said they wanted to order tickets for a play. And I said the people who were supposed to be there to take reservations I guessed were not there; if they gave me their number, I would call them back and see about tickets.

I found a very cluttered desk, which I began organizing. As the phone rang I would pick it up—still there was nobody there—so I just kept taking messages. Shortly after that someone did come in. I’ll always remember, she was an actress in the company, and one of the founders of the company. Her name was Norma Jean Wanvig. She came in and said, “Oh, I’m so glad you’re here. The person who is supposed to be here couldn’t make it.” She said, “I have some things I have to do, so why don’t you just stay here? Here’s the reservation book. You look that through. You can take reservations. You can walk into the theatre and see where all the seats are, so you know exactly where people will be sitting.”

And so I sat at the desk, and no one did come in for quite a long time, so I began just answering the phone, “Hello, Actor’s Workshop. Yes, we’re selling The Crucible. How many tickets did you want?”

It wasn’t until maybe three hours or so later that somebody finally did turn up and wanted to see what I had done, and they were really pleased, and wanted to know could I come back? Well, I was free for a couple of days, so I came back the next day, and met some of the other people. They were having a rehearsal that evening for The Crucible, which was a very successful production. I began sitting in, watching rehearsals, and organizing the office, which was something I did naturally.

Jules Irving and Herb Blau, I found out they were the directors of the company, and they were teaching full-time at San Francisco State College. They were really pleased with what I was doing. Then I began ushering, taking tickets with the people who I had sold them to, and watched the production, and then watched the rehearsals. Someone didn’t turn up at one of the rehearsals, and they asked me if I would like to step in, and I said yes. And so I became an understudy.

In about two or three weeks. I remember meeting with Jules after rehearsal; he was doing the lead in The Crucible. I explained that I was just on vacation; I had to go back to Toronto. They said, “Well, you can’t leave. You mustn’t leave.” That one-week vacation turned into nine months. Then I said, no, I really had to go back—I didn’t have any papers, I was in the country illegally. But I said I really wanted to work with them. I liked what they were doing. Listening to Herb Blau talk about Bertolt Brecht, and doing the American premiere of Brecht’s Mother Courage, and other challenging works. I thought: Now this is something I was really interested in.

I went back to Toronto. I had to have enough money in order to come back. You had to show that you would not become a ward to the state, that you could take care of yourself financially. As the administrator of the Actor’s Workshop, I think I was paid something like $21 a week, but that meant being there around the clock.

We moved to Folsom Street, I think it was, and we had an office in a house there. I lived behind the office: There was a cot and a refrigerator, and if you put food in the refrigerator I ate; if you didn’t, I didn’t eat. I was very thin at the time, but I was very happy. I was doing what I wanted to do, which was to work in theatre full-time.

I was, I think, the only full-time employee. I used whatever title in answering mail: I would say my name as “secretary to the director,” or managing director, general manager—whatever title was appropriate in replying to whatever the mail was, that’s the title I used. I think I made up several titles. That’s how I started with the Actor’s Workshop.

According to some accounts, there was tension between the Actor’s Workshop, especially Herbert Blau, and the city of San Francisco. Was that your observation?

Well, he was very uncompromising, Herb Blau was. He knew what his theatre should be, and he wasn’t ready to cater to what would be the popular kind of fluff that people wanted. They didn’t necessarily want political theatre, challenging theatre. But there were enough who did, enough to keep it going. The kind of plays that were being done, no other company in San Francisco or in the Bay Area was doing that kind of work. We did Waiting for Godot, and The Birthday Party was another premiere. Brecht’s Mother Courage, which was an American premiere.

So we were doing stuff that—we weren’t doing John Loves Mary. Some of the people kept saying, “Well, where is all the kind of fun stuff?” We said, “Well, Waiting for Godot is really very funny.”

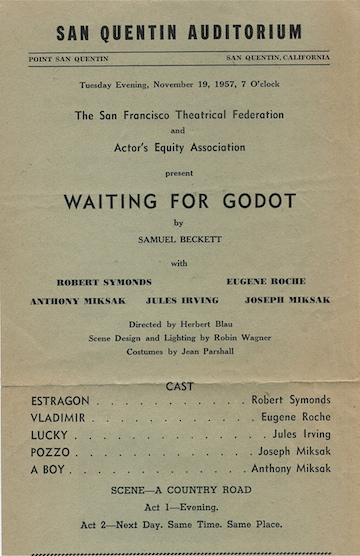

Indeed the Actor’s Workshop might be best remembered for staging Godot at San Quentin State Prison. Could you talk about how the company first came to mount that show?

Oh boy. I think it was Herb Blau at one point was on a sabbatical, and was traveling in Europe, and he came across the play when he was in Paris. He said that he was sending back a copy of this play that he thought we should do.

And so I remember it arriving at the office, and I was sitting there with the secretary, and I looked at it, and there were four characters and a boy. I remember we read this, alternating characters. I didn’t understand what the hell it was I was reading. We laughed at certain things, and then I remember getting to Lucky’s speech, and I didn’t know what that was all about. I had not the vaguest idea. And I thought, “God, he really wants to do this. He thinks this is important. I have no idea why.”

But Herb Blau was brilliant. Beckett once said, “Oh, Herbert Blau is overpoweringly intellectual.” If Samuel Beckett said that about Herb Blau, you can imagine how overpoweringly intellectual Herb Blau was. I used to walk around with a dictionary, and Priscilla [Pointer], Jules’s wife, the two of us used to play dictionary games learning new words. Herb Blau used to say he would never use the same word twice if he could find another word that meant the same thing. So I was always looking up words in the dictionary.

I mean, he was very challenging. But when he spoke, and if it was about Chekhov, he gave you the whole history of Chekhov. He knew everything that you could possibly want to know about Chekhov. He had read all the literature, right? He’d written about it. It was the same with Strindberg, and to a lesser extent Pinter. He wasn’t as impressed with Pinter as he was with Beckett, obviously.

What was it like to perform in the prison—what were the security precautions?

Well, what you did is you went in two at a time. I believe we were told not wear blue jeans, which is what all the inmates wore—they all looked like they were in college or something going to class. I thought they were wearing these striped things that you see in those early movies, but no. It was, you walk up to one gate, and they stamp your hand with a fluorescent stamp, and then you walk down a kind of cattle runway to the next gate, the gate behind would close behind you, and that gate would open, and then you would walk out, and you’d be on a courtyard.

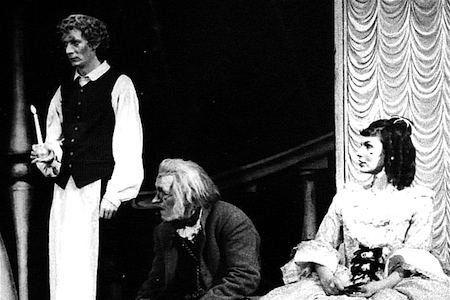

It was really interesting when the Boy made his entrance: He comes on, and the whistles from the crowd of inmates, there were about 1,500 of them in that room, filling the big dining hall with guards with rifles at the ready on catwalks up above, but they were whistling. There was someone there who had their eye on the rope around Lucky’s neck, and on the props at all times. Robin Wagner, who designed it, got locked in overnight, and he spent a night in a cell ’cause he couldn’t get out in time, he was so busy working on the set.

There were so many things that made the whole thing so special, but it was the reception from that audience was just unbelievable: The cheering went on, and the stamping of the feet. I mean, I’ve been to some thrilling first nights for big projects I’ve been involved with, and others that I’ve been to, but I’ve never been to one that was received with such enthusiasm and utter joy as that was. The laughter, the lines—you could have heard a pin drop in the quiet moments. Later the inmates would call each other Gogo and Didi; Pozzo was the warden, Lucky was the guy on death row. They knew exactly what this play was about, and they knew what waiting was about. They wrote a review, the review in the prison paper. Beckett thought it was one of the best reviews of the play that he’d read.

Who from the prison attended? Was every inmate there?

Almost all of them. There were some who were in lockdown. Rick Cluchey, who eventually became a major part of the workshop that we did, was not able to see the play. It was piped into the cell, so a lot of people heard it over the speaker system that they had in all the cells. Rick was in for life without parole. Rick was the one who really helped start the theatre at the prison, and I became his associate, so I sort of introduced him to the work of Samuel Beckett. We eventually got him paroled. He’d been there for under maybe 13 years. He formed his own company, began writing plays, and they were producing his plays. He did it across America. As I say, I introduced him to the work of Samuel Beckett, and he introduced me to Samuel Beckett. I mean, who knows how these things come about? But that’s what happened. That’s how I met Beckett.

How did that meeting come about?

I was at Lincoln Center by then. I was the general manager, actor, I was doing everything—whatever you needed to do in the theatre to make it work. I remember him calling me one day at my home in New York. He said, “Hi, it’s Rick. I’m working with Samuel Beckett. We’re going to Berlin to do Krapp’s Last Tape“—which I had done in San Francisco. “We’re going to do Endgame at the Abbey Theatre, and Beckett would like it if you would do Nagg.” I got a telegram a couple days later: “Approved Mandell as Nagg. Signed Samuel Beckett.” I thought, “My God, this is for real.”

So a couple of weeks later I was on a plane to England, met in London with Rick and Bud Thorpe, and another actor. The next day we were in a cab, and we picked up Samuel Beckett on our way to rehearsal, and he was sitting next to me. I couldn’t believe it. I mean, he said, “Good morning.” I could hardly get it out. It was the most surreal experience.

At rehearsal, there would be 20 to 30 people there, a lot of academics with their notepads. No one was allowed to say much. About the third or fourth day Beckett said, “Well, we’ll do the Nagg/Nell scenes.” I nearly fell over. I said, “Well, Nell isn’t here” [the performer was on her way from Puerto Rico]. He said, “Oh well, why don’t we pull up two chairs? I’ll do Nell, and you do Nagg.” And so we did the whole scene, and it was like something metaphysical happened—I knew how I was supposed to play it. I mean, to do the scene with Samuel Beckett was really quite something. He patted me on the lap and said, “You’re going to be very good.”

Following the 1957 prison performance of Godot, how did Rick Cluchey and the inmates come to create the San Quentin Drama Workshop?

About a year later they had formed their own theatre group. They went to the warden and said they’d like to do plays, and the warden thought they were trying to goof off. He finally agreed to let them do it. He said, “But you’re going to do it on Monday night, which is movie night. So you have to give up your movies.” They said they were serious, they really wanted to do it.

So they began doing plays, and then they did Waiting for Godot, and they invited us. I went. I was watching, and they were in Act 2 already, it was going to be over—no, they were back in Act 1. I spoke to them after the show, and they said the reason for the way they did it was, the only script they could find was published and printed in Theatre Arts magazine; it was bound incorrectly, so that’s what they had. They played it the way it was bound—it was Act 2 mixed with Act 1.

And so I said, “Look, if you’d called me, I would have gotten you scripts or whatever you want.” A couple of days later I got a call from the prison and they said, “You mentioned you wanted to help. Were you serious?” I said I really meant it. They would send someone to drive me over there, and that’s how that began.

Later, when the Actor’s Workshop had a new board of directors, the new secretary of the board heard about this program, and she asked me how I got there, she said, “You don’t drive.” I said, “Well, I call the prison. I have to wait for them to send someone.” She said she’d be happy to drive me there. I said, “But the problem is I’m there for two hours.” She said she had friends and family in Marin, and she could go stay with them. She would drive me there and come pick me up.

Once I invited her to have dinner at the prison cafeteria, waited on by inmates overlooking Richardson’s Bay, which was very beautiful, very romantic—and she could drive. So I married her. So you see, a lot of wonderful things came about.