Theatre scholar and aficionado Marvin Carlson, who serves as the Sidney E. Cohn Distinguished Professor of Theater at CUNY Graduate Center, has spent a lifetime on the aisle, taking in theatre all over the world, but especially in New York, and he recently collected his thoughts about 50 of the most emblematic productions he's seen in a new collection, 10,000 Nights: Highlights from Fifty Years of Theatre-Going. Below are three excerpts, published with the permission of the author and the University of Michigan Press.

1964: After the Fall at the ANTA Washington Square Theatre

Ever since the development of a serious art theatre in the United States early in the 20th century, some visionaries have dreamed of establishing an ongoing repertory theatre for this country that, like the Vienna Burgtheater or the French Comédie-Française, would house an established company devoted to presenting a rotating repertory of the nation’s most distinguished dramas. Among the most significant of these attempts were the Art Theatre of Winthrop Ames, begun in 1909, a number of seasons of the Theatre Guild in the 1940s, and most notably Eva LeGallienne’s American Repertory Theatre in the 1930s. None of these, however, lasted even a decade.

In the late 1950s the theatre world, especially in New York, was astir with plans for a new attempt at this project. The monumental arts and urban development project that would become Lincoln Center was gradually taking shape. In the case of opera and music, existing institutions were to be moved there, but New York had no parallel in a state or city theatre, and at first theatre was not included, but before long a newly established repertory theatre was incorporated into the project, partly under the influence of European models, but also in recognition of the recent rapid growth of the regional theatre movement and the success in particular of the Stratford Festival in Canada. This opened a permanent theatre in 1957 with a thrust stage that was widely seen as a model for modern theatre arrangements and was strongly influential in the creation of the main stage in the Lincoln Center project.

The new theatre was planned to open in 1963, but as is almost invariably the case with large construction projects, there were many delays. The project director was Robert Whitehead, who had long championed a national theatre as a guiding spirit at ANTA (American National Theatre and Academy), originally founded for that purpose. He felt the time pressure keenly, as he had a fledgling company of actors in training for the new venture and two plays commissioned from leading playwrights who were expecting production that year. Their selection for the opening season was perhaps the safest possible, commissioning two new works, one serious and one comic, from the most respected serious and comic dramatists in the American theatre during the previous quarter of a century, Arthur Miller and S.N. Behrman. With a company and plays ready, but with no space for them, Whitehead and the board of directors sought alternatives. An existing Broadway house was rejected, partly because of the expense but also because the planners were dedicated to the concept of a thrust stage in the Stratford model, and wanted to avoid a conventional audience arrangement.

Although the Stratford model clearly inspired a vogue for thrust stages during the 1960s, it should be noted that there was a much closer model at hand for the designers of the new Lincoln Center project, Theodore Mann’s Circle in the Square. Mann, with the actor José Quintero, had founded this theatre in 1951 in Sheridan Square, in the heart of Greenwich Village, where, as its title indicates, it brought then then-new practice of theatre in the round to the New York professional stage. When the theatre moved to Bleecker Street in 1960 it introduced another new arrangement, the first professional stage in New York to seat audiences on three sides of the performing area, though it kept its now less accurate name. When I began attending theatre regularly in New York, I found the Circle in the Square one of the most exciting and innovative of the Off-Broadway venues, producing such works as the stunning American premiere of Jean Genet’s The Balcony in 1960, with Salome Jens as an unforgettably erotic Pony Girl, and commissioning a new set of plays in the increasingly fashionable absurdist style by Thornton Wilder, Plays for Bleecker Street in 1962.

Finally, in the spring of 1963, New York University agreed to lease a plot on its campus for a temporary structure, to be built at the expense of ANTA. Although the model of Stratford was rarely if ever openly evoked, the planners must have had that example in mind when they began referring to the temporary structure as a “steel tent.” The Stratford Festival had famously started in an actual huge tent, whose form was strongly suggested in the recently erected permanent home. In fact, what was christened the ANTA Washington Square Theatre had nothing of the tent about it. It was a characterless steel box, about 20 feet high and more or less square, painted a mustard yellow and from the outside, suggesting a warehouse or storage facility. The simple entrance had a marquee bearing the name ANTA.

Construction on this building began in the summer of 1963, and I often stopped by to watch its rapid progress on my way to other theatres in the area. The NYU campus is located in the center of much of the alternative theatre work in New York. The traditional heart of such work borders the campus on the west, in Greenwich Village, with the Sullivan Street Playhouse (home of The Fantasticks) and O’Neill’s Provincetown Playhouse essentially on the borders of the University (much to their disadvantage, since the latter was demolished in 2008 to provide space for university expansion). By the 1960s, Village culture had extended to the south of the University as well, most notably along Bleecker Street, as the relocation of the Circle in the Square suggests. In fact the new ANTA Washington Square Theatre, while surrounded by university structures, was only one block north and two west from the Circle in the Square.

The ANTA Washington Square Theatre opened in January with Arthur Miller’s much-anticipated new work, After the Fall, his first full-length play since The Crucible 10 years before. I attended the play early in February, in the midst of a bitter cold snap, reminding me that the new venture was not near any convenient subway. Thus walking was the most convenient way to attend the theatre. Located in the midst of a group of small streets normally serving only campus traffic, the new theatre was the center of a massive gridlock as hundreds of taxis, limousines, and private vehicles converged on it. I even noted a few motor scooters and bicycles parked near the entrance, in defiance of the bitter weather. The steel fortress-like exterior was even more forbidding in these circumstances, but the interior, designed by Jo Mielziner and Eero Saarinen, was surprisingly warm and attractive, though still very basic. The interior walls, seats, and floor coverings were blue, and the 1,200 seats were wrapped around a thrust stage. One entered on a level with the back row of seats, some 60 feet from the stage, which was located 15 feet or so below street level.

The much-publicized thrust stage was for this production far from the clear and simple configuration at Stratford. There was almost no scenery in the conventional sense, only a chair for the narrator/protagonist and a concentration camp tower. Mielziner had built up on the thrust stage a complex collection of irregular overlapping planes, like rocky outcroppings, providing an effective playing area for a play composed of the fragmented and overlapping memories of the protagonist, Quentin. Quentin was played by Jason Robards Jr., who had established himself during the previous decade as America’s leading interpreter of O’Neill, in The Iceman Cometh and A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, both opening in 1956 and both directed by José Quintero.

After the Fall was, not surprisingly, directed by Elia Kazan, then America’s best-known director, who had first staged most of the major works of Williams and Miller, and who had now joined Whitehead as codirector of the ANTA Washington Square project. Kazan also directed the new Behrman play that closed this first season. Quintero, with his current close association to O’Neill, was selected to direct the third offering and the only revival, O’Neill’s 1928 Marco Millions, not seen in New York since 1930.

The opening of this major new theatrical venture, the participation of many of the leading figures—directors, actors, designers, and dramatists—and the premiere of the first new work in almost a decade by the most honored living American playwright all would have made this production one of the most newsworthy theatre events of the decade, but all were in fact overshadowed by the content of the play, since Miller had decided to present a story with such detailed resemblance to his own life that it was essentially taken to be autobiographical. Quentin is a Jewish intellectual who begins the play by stepping out of the stage picture and moving directly down to the tip of the large stage and quietly addressing the audience as if speaking to a close friend (or perhaps a psychiatrist). In a series of nonconsecutive and overlapping flashbacks that make up the rest of the evening, he recalls and reflects upon his two previous marriages as he contemplates a third, to the German woman Holga. Many of the play’s details inevitably recalled to audiences the best-known elements of Miller’s life aside from his plays—his highly publicized marriage with the actress and sex symbol Marilyn Monroe during the 1950s and his refusal to name names during the anticommunist hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956.

Both details were prominent features of the play. In the play, the latter event is primarily reflected in the conflict between Quentin and his friend Martin, a Communist who does reveal his associates, outraging Quentin and ending their long friendship. Martin was universally seen as based on Kazan, who had had an identical falling out with Miller over exactly this issue. Clearly the rift was subsequently healed, though Kazan was left in the odd position of directing a play in which his avatar (played by Ralph Meeker, whom Kazan had directed a decade before as the replacement for Marlon Brando in Streetcar) is presented in a most unfavorable light. At the time of this production, Miller had already married his third wife, the Austrian-born photographer Inge Morath, who seems clearly to be represented by Holga in the play. Holga was created by Salome Jens, with a still palpable but much subdued trace of the sexual seductiveness she had shown as the Pony Girl in The Balcony. Kazan insisted that the characters in the play were absolutely not to be equated with anyone in Miller’s real life, but virtually no one believed this then or since.

Nor did Kazan do anything to diminish the much more discussed feature in the play, the character Maggie. Her marriage to Quentin, drug problems, and eventual suicide were all closely reminiscent of Monroe, whose death had occurred only a year and a half before the play opened. On the contrary, Kazan cast Barbara Loden, another blonde sex symbol, whose resemblance to Monroe Kazan exaggerated by giving her a bouffant blond wig and highly revealing dress to wear and encouraging her (or at least not discouraging her) from performing in a husky voice and with mannerisms that, as several reviewers suggested, came close to parodies of those of Monroe, who had herself become a kind of self-parody during her later years. Her emotional disputes with Robards were the highlights of the long evening (the play, even after serious cutting, ran nearly three hours), but despite the quality of the acting, there was an inescapable air of somewhat tawdry voyeurism or even exploitation about it.

As for the repertory company itself, neither Whitehead nor Kazan remained associated with it even long enough to see it move from its temporary quarters to its permanent home in Lincoln Center. After the Fall, despite its mixed reception, was on the whole a success, but it was the only one. The other new work, S. N. Behrman’s But for Whom Charlie, and the single revival, O’Neill’s Marco Millions, received indifferent reviews and were poorly attended. Kazan’s production of The Changeling, the company’s first attempt at a classic work and the opening of the second season, was universally condemned. A new Arthur Miller work, Incident at Vichy, finally gained success, but it was too late. In December the board sought to replace Whitehead, and he resigned, soon after followed by Kazan. By the end of the year the new venture, still not in its new building, was drifting rudderless, a situation that would continue, with varying degrees of urgency, for the next two decades.

1965: Peter Brook’s Marat/Sade

Ironically, in the spring of 1964, with the Lincoln Center company in Washington Square having presented the three plays of its first season, with two of them so indifferently received that they were not extended into the summer, Lincoln Center itself was host to one of the most outstanding theatre events of the season—the visit of the British Royal Shakespeare Company presenting Paul Scofield in King Lear, directed by Peter Brook. The Royal Shakespeare Company was just establishing an international reputation, thanks to Peter Hall, who became artistic director in 1960, and Peter Brook, who joined as resident director in Although both company and director were being much talked of among theatre people in 1964, Lear was the first time that I, and most New York theatregoers, had been able to see the work of either.

The work for most of us was a revelation. The Shakespeare we had seen up until then, especially in major theatres, had normally been performed in a highly predictable traditional manner, what Brook himself famously characterized as “deadly theatre.” Lear was so unconventional as to be almost an assault. The almost empty stage, the starkly presentational style, the turning on of the houselights during the performance, all likely influenced by the anti-illusionistic theatre of Brecht, kept spectators constantly off balance, and the bold and often almost overwhelming physicality of the production left a lasting impression. I had never seen such onstage violence as Lear and his soldiers destroying their dining hall, nor so stunning an effect as the giant metal sheets suspended in an empty stage and set vibrating to suggest the storm.

Lear, already one of Shakespeare’s darkest and most nihilistic plays, became even darker and more nihilistic in Brook’s hands. As one example, the rebellion of the servant against Cornwall as he is putting out Gloucester’s eyes, the only touch of humanity in that horrific scene, was cut. The bleak, empty landscape of the play and its aura of hopelessness was, as Brook admitted, much influenced by Jan Kott’s recent writing on the play, which placed Lear in the world of Samuel Beckett. Appropriately, Kott’s book, Shakespeare Our Contemporary, was on sale in the lobby of the theatre. The production was not given at the City Center, the traditional home for such international traveling shows, but at the newly completed State Theatre at Lincoln Center. The Vivian Beaumont, designed to house the spoken drama, was still under construction, and the State Theatre, designed for ballet, was soon discovered to have some of the worst acoustics in the city. In fact, with these sound problems and the sound and fury of the production itself, a good deal of the Shakespeare text was lost, but so powerful and overwhelming was the total effect that I left thinking, as did many, that Peter Brook would be a name to be reckoned with in the years to come.

It was with those memories in mind that the New York theatre received word that a new, and even more shocking Brook production, Peter Weiss’s The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, would be arriving late the following year. Indeed, in the early months of 1964 New York papers reported that Brook was working with a group of RSC actors and the American director Charles Marowitz in a new laboratory theatre exploring the performance implications of the writings of Antonin Artaud, the lab to be called the “Theatre of Cruelty,” a much-debated central term of that author. Although Brook’s production brought the name of Artaud into the mainstream of New York theatre discussion, those interested in experimental work had been aware of his writings since the late 1950s, when I began regularly attending New York theatre. The Living Theatre regularly evoked him as a major inspiration, and when the works of Genet began to appear in the early 1960s off-Off-Broadway, knowledgeable critics frequently mentioned an Artaudian influence.

Fortunately for interested theatregoers who did not read French, an English collection of key essays by Artaud, called The Theatre and Its Double, appeared from Grove Press in 1958 and shortly became essential reading for anyone interested in current experimental work. During the next decade, just as students of contemporary theatre needed to read the Tulane Drama Review (changed in 1967 after its move to New York University to TDR: The Drama Review), they also generally built up libraries of central new dramatic works by collecting Grove Press publications.

Grove Press began with editions of the French absurdists—Beckett, Ionesco, Genet, but continued with Pinter, Stoppard, Behan, Gelber, Albee, and indeed most of the major new dramatists that emerged in the 1960s. It was by far the predominant press represented on my bookshelf of contemporary drama.

Although Brook’s production brought the term “theatre of cruelty” into the critical mainstream, there was never much of a consensus concerning its exact meaning. Interpretations ranged from a kind of ascetic purity and rigor to a kind of Dionysian orgy. Despite Artaud’s own warning that the term did not simply involve such matters as the shedding of blood, the sensational appeal of the latter tended to dominate public use of the term, and Marat/Sade, easily the most famous product of Brook’s laboratory, did much to reinforce this view, with its apparently scarcely controlled displays of physical and emotional extremes. The production came with stories of considerable physical and emotional damage suffered by the company during the workshops and rehearsals, and the production on stage called up such extreme efforts on the part of the company that such reports seemed all too likely.

By this time, thanks to his previous Lear and glowing reports on Marat/Sade from Europe, interest in Brook’s work was so great that the company was presented not in a venue like the clearly marginal New York State Theatre, but in the Martin Beck Theatre, on West 45th Street in the heart of the Broadway theatre district. The production opened during the Christmas holidays of 1965 and was by far my most memorable theatre experience of that school vacation, or indeed for some time before and after.

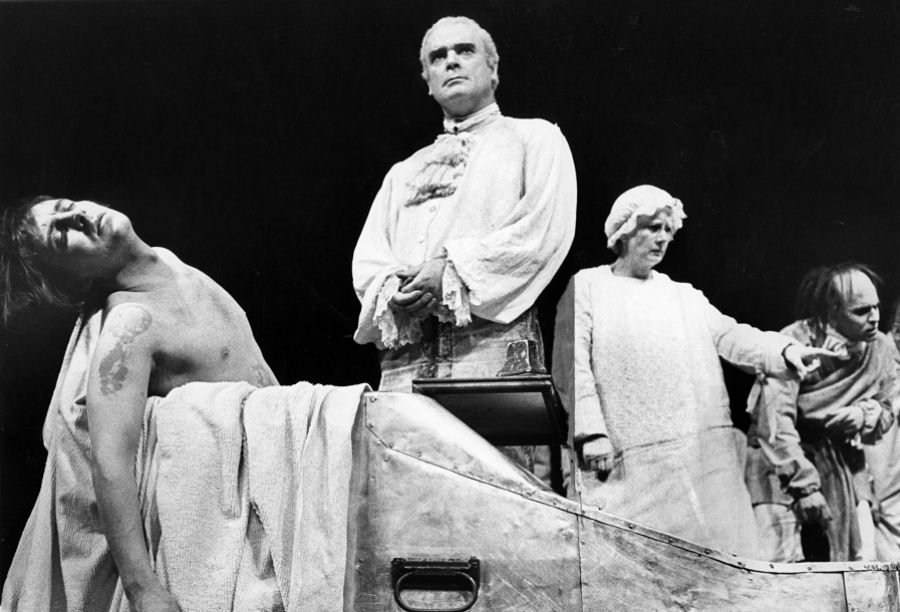

Lear had prepared me for a violent and confrontational performance, for houselights unconventionally up, and for extreme physicality, but even so, Marat/Sade continually shocked in its extremes and dazzled in the originality of its images. Coulmier and his family came in through the audience and joined us, though in a slightly elevated box on the right-hand side, but other cast members were seated among us, and the most violent of the patients regularly seemed on the brink of directly attacking the audience. The stage was a fairly simple one, representing the asylum bathhouse, with appropriate pipes and fittings on the two side walls and a plain blank industrial wall at the rear. There was a frequently used pit downstage and upstage a circle of wooden platforms, slotted to allow the bathwater to drain away, out of which the actors would build crude replicas of scenic units, tumbrels, or guillotines. The large cast was in constant agitation except the catatonic ones, who added their own disturbing note to the overall picture), and although they formed highly effective groupings for musical or physical choric numbers, total dissolution and chaos seemed always just moments away. One of the most disappointing aspects of the subsequent film, which captures many of the visual details, is that the sense of immediate physical danger, an essential part of the experience of the actual production, is completely missing. Of course the film medium itself inevitably removes all sense of physical immediacy, but Brook somewhat inexplicably increased this distance by placing the presumed real audience in the film behind a protective metal cage, as if they were not in the theatre, so the threat of the madmen breaking out was totally absent.

Along with the physical violence, there was a constant threat of uncontrolled sexuality. Perhaps this was most obvious in the “copulation round,” where the entire company engaged in frantic mimed sexual activity to accompany a song equating revolution with sexual license. Still a mordant sexuality hung over most of the production. Duperret, the “true love” of Corday, described in the text as an erotomaniac, seized every opportunity to try to mount not only the heroine, but any female within reach. Corday, suffering from sleeping sickness, could only push him away with the greatest effort. The somnambulistic Corday was played by Glenda Jackson, who had joined the RSC for the Theatre of Cruelty season, and whom I will always associate with the brilliant RSC productions of the 1960s. Despite her passivity, Jackson’s Corday was far from devoid of sexual interest. Her desire to stab Marat in his bath clearly came in large part from an erotic drive. Then, in one of Brook’s most memorable visual innovations, where the text calls for her to whip the half-naked de Sade as he expounds his philosophy, Brook had her sweep the back of the kneeling de Sade not with a whip, but with her long tresses, as he gasped in erotic pain and pleasure.

The two other leading actors, Patrick Magee as de Sade and Ian Richardson as Marat, were also new to the New York stage, although much better known in England. Richardson had been for several years a leading figure at the RSC and Magee was closely associated with the work of Samuel Beckett, who in fact created Krapp’s Last Tape for him. They provided a marvelous contrast, Magee cold and ironic, Richardson frantic and passionately agitated. In terms of the production’s eroticism, de Sade of course provided constant ties between revolution and the erotic through his text, but Marat’s physicality created an even stronger impression, and Richardson provided one of the most shocking moments of the production, when he emerged from his bath to move upstage, providing the audience with the first view of nude male buttocks ever displayed on a Broadway stage. During the next decade stage nudity became almost a cliché in the New York theatre, but this first example added distinctly to the overall sense of a production exceeding all previous boundaries.

I loved the quirky music provided by Richard Peaslee for the production, which used songs in a Brechtian manner, not so much to advance the action in the manner of the Broadway musicals of that time, as to comment ironically upon it. Probably the most memorable, however, were Brook’s visual images—the actors advancing in ranks to be guillotined, then dropping into a pit and piling up so that their apparently separated heads formed a living pyramid facing the audience; the manically smiling member of the clown chorus pouring buckets of blood (red for the aristocrats, blue for the king, white for Marat) into a large onstage funnel after each death scene; the monstrous puppet figures representing the King, with a crowned cabbage for a head, and the personal and public monsters that appeared in Marat’s nightmare. These latter figures for many in the audience suggested the creations of New York’s Bread and Puppet theatre, just then coming to prominence as a major part of the anti-war movement. About them I will say more later.

The conclusion of the production was as original, as theatrical, and as disturbing as the production as a whole. De Sade’s entertainment, always on the brink of descending into anarchy, finally apparently sprang out of control. The final choric number became more and more frantic, the scene turned into a riot, with nurses and the watching Coulmiers fleeing, and muscular guards wading into the melee beating the inmates with heavy clubs. Finally the stage was cleared and silence descended.

The stunned audience joined in the silence, but after a moment or two burst into thunderous applause. No actors appeared for some time while the applause continued. Finally they appeared, but still in character, escorted by the guards and nurses to line up across the stage and stare dumbly at the audience, without bowing or acknowledging the applause. Eventually the applause diminished, faltered, and stopped. The cast remained unmoving, staring out into the auditorium, alien and deeply disturbing in their immobility. At last the silenced audience began to leave, and as I reached the exit I looked back to see that line of passive lunatics still silently watching us depart, one final image to add to the many I still retain of this remarkable production.

2007: August Wilson’s Radio Golf

My introduction to the work of August Wilson was not propitious. Between 1979 and 1986 I was teaching at Indiana University, and this restricted my New York theatregoing primarily to vacations there or when passing through coming or going to Europe. Eager to seize every opportunity to attend New York theatre, I would even from time to time go to a show the night I arrived from Europe, weary and jet-lagged, hardly an ideal viewing situation. That was the situation in the fall of 1984 when I attended Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Wilson’s first New York show, the same day I returned from several days seeing theatre in Germany’s Ruhr Valley. It was clear that this was a major new voice in playwriting, supported by very strong acting, especially by Theresa Merritt as Ma and Charles Dutton as Levee. But seen through a jet-lagged fog, it registered only enough to convince me that I must return to this author at the next available opportunity.

This opportunity did not in fact present itself until Fences, with James Earl Jones, which I saw the night after its opening in May 1987 at the 46th Street Theatre. In the previous fall my wife and I had moved to New York, where I began teaching at the Graduate Center of the City University. Our first apartment there was in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and so for the first time in my life only a 30- to 40-minute subway ride separated me from central Manhattan, instead of a lengthy drive from Cornell or an even more lengthy flight from Indiana. As a result I began attending theatre almost nightly, as I had done on my previous visits to New York and European cities.

One of the many pleasures of this steady access to New York theatre fare over the following years was being able to attend each of the new contributions to August Wilson’s developing Pittsburgh Cycle, which appeared at fairly regular intervals for the next twenty years. I, like many others, looked forward to each new contribution to this massive project very much as, during the 1960s, I looked forward to each new film by Fellini, Bergman, or Truffaut. All of these shared an artistic interconnection and cumulative effect, but Wilson’s project, as it began to emerge, had the extra appeal of presenting in its totality a panoramic view of black life in American over an entire century. Although all of the plays except Ma Rainey were set in a single black neighborhood in Pittsburgh, and some characters reappear, each play takes up a different part of that community, rather in the manner of Balzac’s series of novels in his Comédie humaine. Rather surprisingly, the only other dramatic author I am aware of who has undertaken a similar project has been another leading black American, Ed Bullins, whose “Twentieth Century Cycle,” begun in 1969 and still incomplete, now numbers 20 works.

Fences and the following work, The Piano Lesson, both won Pulitzer Prizes and made Wilson during the next decade the most-often-produced living American dramatist. Like most theatregoers of the time, I was fascinated by these blends of traditional American realistic family drama with Wilson’s particular gift for poetic expression and a hint of hidden, perhaps otherworldly, forces at work behind these everyday facades.

By the early 1990s, although the plays were not created in chronological sequence, the overall outline of Wilson’s project had become clear, and added to my anticipation of each new work was that of how various decades, especially those within my own memory, would be reflected in Wilson’s dramatic world. This certainly played into my enjoyment of Fences, set in the first decade of which I have a clear memory, the 1950s, and of the subsequent decades, from Two Trains Running, set in the 1960s, to the final work in the cycle and in Wilson’s career, Radio Golf, set in the 1990s.

Only one work in the series was not presented on Broadway. This was Jitney, set in a gypsy cab station in Wilson’s Pittsburgh Hill during the 1970s. Wilson’s previous Seven Guitars had not been a financial success on Broadway in 1996, and Jitney, an earlier work that Mr. Wilson’s reputation had led to a number of productions elsewhere in the country, attracted no Broadway producers. Fortunately Second Stage decided to bring the play to New York in 2000. Second Stage was founded in 1979 to give a second showing to plays by contemporary American authors who in the opinion of the theatre’s directors had not received adequate attention for their first showing. Normally that first showing took place in New York, but Jitney was technically qualified because of its regional presentations. Although located in the heart of midtown, indeed within a block of several Broadway houses, Second Stage is ranked as Off-Broadway because it contains less than 300 seats. In this smaller, but centrally located, space, Jitney had a successful run, and reopened Broadway to the four Wilson works to appear in the new century, completing the cycle.

The final play in the cycle and in Wilson’s canon, Radio Golf, premiered in New Haven in the spring of 2005, and shortly after its opening, Wilson announced that he had been diagnosed with inoperable liver cancer. He died early that October, when the play had not yet been offered in New York. A mark of the high regard in which he was held, however, was that two weeks after his death, a Broadway theatre, the Virginia, was renamed the August Wilson Theatre. A more appropriate house to rename would have been the Walter Kerr, which had presented four Wilson plays while the Virginia had presented only King Hedley II, but doubtless Rocco Landesman, who had just that year purchased the five-theatre Jujamcyn group, which contained both houses, preferred to keep the name of the well-known critic and drop that of the wife of the previous owner of the house.

Along with several hundred others, I attended the rededication ceremony on Oct. 17. After a short celebration inside the theatre, which included a number of tributes, a song from Ma Rainey, and a moving funeral scene from Seven Guitars, all moved outside for the cutting of a red ribbon and the first illumination of the new name on the marquee. Across the long side of the marquee was a huge copy of Wilson’s signature, in white letters against a dark background, an arrangement copied on the marquee of the rechristened Stephen Sondheim Theatre four years later.

Wilson was the third playwright to be so honored among the 40 Broadway houses, and the first African American. His two predecessors were Eugene O’Neill (in 1959) and Neil Simon (in 1977). A representative of the theatre expressed the hope that Wilson’s last play would be given its New York premiere in the theatre that now bore his name, but that was not to be. The first show presented in the renamed theatre was the musical Jersey Boys, which proved such a great success that it was still running when Radio Golf finally came to New York. The Walter Kerr was occupied with another musical, Grey Gardens, and so when Radio Golf finally came to New York in May 2007, it opened in perhaps an even more appropriate venue, the less popular Cort Theatre, on the unfashionable east side of Broadway, the theatre where Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom had introduced Wilson to New York almost a quarter of a century before.

Most appraisals of Wilson’s cycle consider Radio Golf one of its weaker parts, but it, along with Gem of the Ocean, presented at the Walter Kerr two years earlier, were among my favorites, since as the first and last plays in the century survey and as the last two actually written, they provide a kind of overarching series of reference to all of the others and are most centrally concerned with the dynamics of memory and memorialization that have become of steadily greater interest to me personally as my theatregoing has extended through more and more years of experience.

The central bearer of history in the cycle is Aunt Ester, who, aged 285 when the cycle begins in 1904 with Gem of the Ocean, provides a living connection with the African-American past. Although her death is reported in the 1980s in King Hedley II, her spirit suffuses the cycle and haunts the final play, Radio Golf, which on one level is a kind of modern morality play, with its protagonist, Harmond Wilkes, torn between his political and economic ambitions (he is an upwardly mobile real estate developer and a potential candidate for Pittsburgh’s first black mayor) and his morality and connections to his roots (a major development by his firm has illegally obtained and plans to destroy the home, and by implication the cultural memory, of Aunt Ester).

Having seen the marvelous interpretation of Phylicia Rashad as Aunt Ester in Gem of the Ocean just over two years before, that larger-than-life personage, that house, and that world were clearly in my memory as their erasure was threatened in this work. Those were the central evocations, but the play was full of others. Situations, references to historical events of the past century, even lines and images from previous plays kept sounding echoes of previous works, as did the actual bodies of some of the actors. The two characters who spoke most clearly for preserving the memory of the part were Sterling Johnson and Elder Joseph Barlow, both played by actors whom I had recently seen in Gem of the Ocean.

In Radio Golf Anthony Chisholm played Barlow, the threatened present owner of Aunt Ester’s house and the descendent of the troubled Citizen Barlow, whose soul is cleansed by Aunt Ester in Gem of the Ocean. In the earlier play, the first Barlow was played by John Earl Jelks, who in Radio Golf reappears as a citizen of the neighborhood who repaints the house in order to give it a more presentable appearance.

A great part of the power of the production for me came from the flood of memories it evoked, not only of a quarter-century of experiencing the development of Wilson’s monumental project within the theatre, but also of the century of American history that cycle and this play evoked, a good deal of which resonated with my own memories from the Second World War onward. At the center of the play, however, was the tension between a troubled past and a future equally troubled, not least by overly optimistic visions of an assimilated, “progressive” black population. The effective, almost allegorical setting by David Gallo contrasted the run-down threatened neighborhood of Aunt Ester’s home with Wilkes’s sleek but soulless contemporary real estate office, dominated by a photograph of Tiger Woods, clearly symbolic of the black man who had “made it” in the sport most associated with the economically privileged white upper class. But for audience members in May 2007 an even more potent such symbol was available, since at the beginning of that month Barack Obama had announced his candidacy for president, a major real-life realization of Wilkes’s dream of running to be the first black mayor of Pittsburgh. In the enthusiasm and optimism of that moment, Wilson’s less than celebratory depiction of such an achievement sounded an unusual cautionary note, but as the dreams of a “postracial” America have steadily faded, the more nuanced racial negotiations of Wilson, in this drama and in his entire cycle, have provided us with a far more complex and informed insight into the ongoing dynamics of race in American culture.