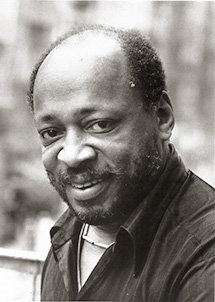

Steve Carter, who turns 88 this November, is one of the most significant playwrights to have established his career with New York City’s Negro Ensemble Company, which just celebrated its 50th anniversary, and with Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theater. Among Carter’s notable plays are One Last Look, produced off-Off-Broadway in 1967; his Caribbean trilogy: Eden (1975), Nevis Mountain Dew (1978), and Dame Lorraine (1981); House of Shadows (1984); the musical Shoot Me While I’m Happy (1986); Pecong (1990); Spiele ’36 or the Fourth Medal (1991).

I spoke with Carter via telephone; he now lives in Houston, Texas.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: Considering the good reviews you received for some of your New York productions, I am surprised that none of your plays were produced on Broadway. Was there ever any talk about that?

STEVE CARTER: It is a combination of bad luck and common sense. There was this fellow—the guy who eventually produced the original production of The Wiz, Kenneth Harper. He wanted badly to take Eden to Broadway and started to work on it, but he died. He spoke to me and to Doug [Douglas Turner Ward] about the possibility of moving it. I didn’t necessarily want it to go to Broadway. My personal feeling was that the play was a little too intimate to be received well in a big house. I really liked my productions at the NEC and at Victory Gardens because they were smaller theatres. I liked the intimacy.

Eden wasn’t the only one there was talk about moving; there was talk about moving Nevis, too, but I didn’t want that. At the time, Nevis was always compared to Whose Life Is It Anyway?—they came out at the same time. Whose Life was on Broadway already. It was getting a lot of publicity because it was not doing as well as they thought it would do. As a matter of fact, at one point they even put Mary Tyler Moore in the lead role, which was being played by a man—it is a male’s role. They changed it so Mary Tyler Moore could play the role. It was not all that successful.

Broadway, to me, was never really the alpha and omega of theatre. I was happy with regional theatre. I actually like regional theatre more than I do the big Broadway productions. I like regional theatre because it brings theatre all over the country. I always touted regional theatre.

What would you say you strive to do as a playwright?

I really wrote the plays to entertain my family and my friends. I just thought that if they had a good time, that was enough for me. The fact that they were produced by the NEC and Victory Gardens and other theatres—all of that was a bonus. In those days, I did not want to think outside the NEC. I loved what the NEC was then, and I loved doing my plays at the St. Mark’s Playhouse. It was a family affair down there. Everybody felt so close to each other. We were all developing. That was a lot of fun.

I did not have high moral reasons for my plays to be done; I just wanted to have enjoyment. When people started saying they were melodramas, that was fine with me because the minute I would see those little handkerchiefs come out and people start crying, I would say, “I got them.” That is all I ever wanted.

You just talked about NEC. What did you gain from producing at Victory Gardens?

It was the first time my plays were produced in a so-called white theatre. I don’t think Dennis [Zacek] would approve of that term, “white theatre,” because the Victory Gardens at that time just produced plays—it did not matter what color or nationality the playwright was, Dennis just produced plays. It was his intention to produce plays that really reflected the ethnic makeup of Chicago: He would produce plays by Hispanics, blacks, Latinos, Jews, or whatever—he just produced plays. I liked that theatre because it was small and intimate and they were not afraid to take chances. I was treated very well at the Victory Gardens and I was very happy there.

But you are very big on the Negro Ensemble Company

I mention the NEC a lot because they gave me a lot of opportunities to do many things. When something went wrong with a set or something, Doug would say, “Steve, we need a cactus—a prop for the stage. Design one.” When we had trouble with a certain item, a coffin that was made for the set and could not even fit in the door, Doug said, “I need a coffin you can escape from. Design it and have the tech man make it.” I was able to do that. On The Sty of the Blind Pig, Doug said, “We don’t have the money for a costume designer. You do the costumes.” And I was able to do that. Two summers in a row the NEC did theatre in the street and that was satisfying, risky and tough in spots, but it was satisfying. We went all over the city.

There was a play that we did that was spectacular, Black Circles ’Round Angela. It was written by Hazel Bryant. Her only connection to the NEC was the fact that she was also an artistic director of the Afro-American Total Theatre. She wrote the play based on a record put out by Nina Simone about four different black women: Peaches, Saffronia, Sweet thing, and Aunt Sarah. Hazel wrote this play connecting these four black women with Angela Davis.

The City of New York sponsored this theatre venture in all five boroughs, and the NEC was chosen to go around. One night we had to go to—I think it was 148th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam. In order to do this every night, the block coordinator was always supposed to call Broadway Maintenance in order for us to hook our equipment into the base of lampposts on the street. That is where we got our power from, the lampposts. They would call Broadway Maintenance ahead of time and get permission to plug in there, and somebody from Broadway Maintenance would always be there to plug us in. This lady, who was in charge of the block, got her information wrong and she called Con Edison—Con Edison didn’t know anything about this. They were not involved. They could not help us. So when we got there we had no place to put our power, no place to hook up, and she suggested that we hook up to her apartment building. She got a whole lot of different extension cords; we hooked up there. And the minute we turned on our power, it blew out all of our circuit power. We then had no power and no lights on the street. The people on that block didn’t really want us there performing because it meant they could not park on the block. When we were setting up, they started driving over our set material and everything. They just didn’t want us there. When it came time for the curtain, I just got on the stage and explained that we were still going to perform even though we had no power. And I said, “For those of you who are interested, be very quiet and you can hear us.”

And the minute I said that, everything changed. All those people went into their apartments—the whole block got lamps, flashlights, and they turned on their lamps in their windows and shone the light down on us. Some of the cars drove up to the set and turned on their headlights and gave us light from their cars. All I can say is all of the performers —Colostine Boatwright, Charliese Drakeford, Sharon Capel, Marilyn Coleman, Yvonne Smith, and Carl Rafik Taylor—were excellent all the time, but on this occasion, all six of them surpassed their usual excellence in those roles. Everything was right. We had a huge standing ovation afterward. It was just a glorious night. You really had to be there to experience it. This was the highlight of what I thought street theatre should be. I always call it my spectacular but unknown night in Harlem.

Which of your plays do you think represents you best?

My favorite play of the ones I have written is not everyone else’s favorite. My favorite play is Dame Lorraine, and that is because I always liked the relationship between the two older people, the mother and father. It expresses me the most because it has as much harshness as it has tenderness.

Speaking of harshness and tenderness, I recently heard about Novella Nelson, who died in September.

Oh, I admired Novella Nelson so very much. She and Frances Foster were signed to take over the roles in Having Our Say from Mary Alice and Gloria Foster when they were leaving the Broadway show during the initial run. Novella and Frances signed to play the two sisters. Then Frances Foster had a stroke. Well, the producers were looking around for somebody to replace her. Novella actually talked them into keeping Frances—waiting to see the result of the stroke, to see if she would pull out of it. They agreed to wait for a little while.

Novella Nelson would go to the hospital every day to visit Frances, and they would rehearse. One day—and I saw this more than once—Frances was recovering but she could not walk very well. She was dragging one leg. There were Novella Nelson and Frances Foster walking down the hallway—Novella Nelson pulling Frances’s pole, the one that held all of the intravenous bottles and everything. They were rehearsing—Novella Nelson had the script in her hand. Frances was very afraid she would lose the part, because she said, “That is the only thing I know how to do—to act. I can’t do anything else.” They became sisters right there in the hospital. That is why they were so damn good in the play. Both of these ladies are gone now. Novella was a very giving person—a very giving actress.

What moment or incident do you think defines playwright Steve Carter?

Well, I will tell you when I started, I just wanted to achieve four things, and all four happened very early on in my career. One was that ever since I had heard of theatre, the first black theatre I heard of was the Karamu House in Cleveland, I wanted to have a play produced there. And then I always wanted a play to be chosen as one of the 10 best plays of the year by Otis Guernsey. The third was to have a play produced in London, on the London stage. And the fourth was to have a play produced on the mainstage of the NEC. All four happened.

Will you share some of your experiences or insights about your plays being produced internationally?

Well, I have only seen one. I saw Pecong when it was produced in London. I think it was 1992. Although Eden and Nevis were done there, I never saw them there. The Tricycle Theatre brought me over to see Pecong. My plays were also done in Canada and a couple of the Caribbean Islands. I heard that a group from England had taken One Last Look to Hong Kong, when it was still under the British rule.

What advice do you have for emerging playwrights?

My advice to emerging playwrights is: If success does not come with your first play, don’t give up. Keep writing. What all playwrights need is a commitment to writing. All playwrights need to think of writing plays as a great love affair, and just continue with it.

How would you like to be remembered?

Most of the people who I would like to remember me, they are being remembered. I don’t know how I would like to be remembered. There are/were people who enjoy watching my plays. I hope they keep the memories of them alive. I certainly would like my plays to be remembered. I would like to think that somebody is still doing them—that they would mean something to somebody. I have not done anything spectacular. I am a journeyman, and that is what I like. I like being in all phases of the theatre.