In a particularly disturbing moment in Thomas and Sally, a new play by Thomas Bradshaw, a 41-year-old Thomas Jefferson takes the 15-year-old Sally Hemings’s face in his hands and kisses her. “I love you, Sally,” he says. Then, without asking her permission, he starts to undress her. For actor Tara Pacheco, who played Hemings every night in the production at Marin Theatre Company (MTC), the moment was fraught. “She’s being kissed, and she’s not consenting to that initiated sexual relationship at all,” Pacheco explained recently. “She kissed him, but it’s the classic consenting to one thing doesn’t mean you’re consenting to something else.”

That’s not the only disturbing scene in the controversial play, which recently had its world premiere at MTC, located in Mill Valley, Calif. In the scene immediately following that kiss, Hemings and Jefferson are spooning in bed, naked and laughing. Regina Victor, who saw the play and wrote an essay about it, was less than amused. “The initial scene with Sally where he kisses her and takes her bodice off, she looks very uncomfortable, which is why I was so thrown by the seemingly consensual aftermath,” Victor said.

The central question of Bradshaw’s play—whether Sally Hemings, who as Jefferson’s slave was his legal property, could have loved her master, who fathered six of her children—has made Thomas and Sally the locus of a veritable firestorm of public protest and criticism. With that backlash have arisen questions of how sexual assault and slavery history can and should be portrayed onstage.

Almost every night during the production’s run, Sept. 28-Oct. 29, a group of protesters have been handing out fliers in front of the theatre, reading in part: “Do not support this play or Marin Theatre Company. Ask for a refund and let Marin Theatre Company know why. Black women have been crying out to Marin Theatre Company that they are harming us with this play and their ad campaign that perpetuate the Jezebel stereotype about black women.”

Meanwhile MTC’s Facebook page has been overrun with reviews from patrons calling the play “deplorable” and “ignorant and unethical,” and claiming that it “romanticizes child rape.” Last week an open letter was released by 13 black artists, calling for a public apology from MTC. The letter has received over 1,600 signatures, among them playwrights Dominique Morisseau and Lauren Gunderson (both of whom have affiliations with MTC). Any theatre company who mounts shows on sensitive subjects can be expected to face angry letters from audience members. But it’s rare for a production to trigger not just negative reviews from critics and patrons but open letters and public protests. In fact, reviewers weren’t universally negative about Thomas and Sally, with the San Francisco Chronicle’s Lily Janiak calling it “an epic piece of theatre.”

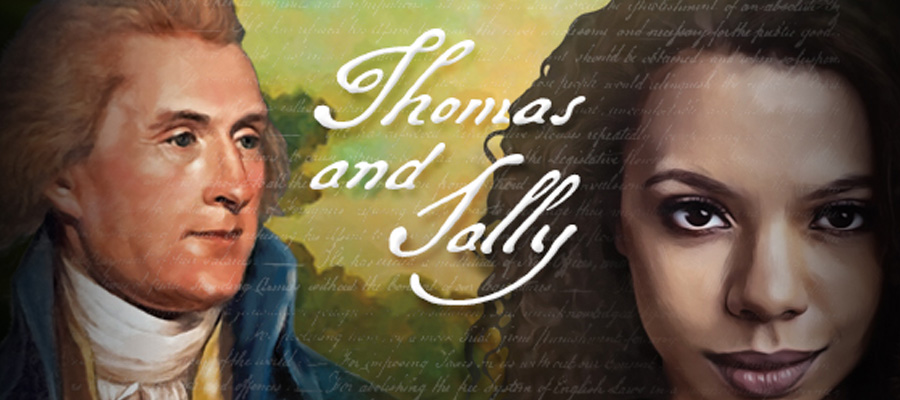

While most artists dream that their work will inspire a variety of passionate reactions, protests of this kind are another matter. In fact, the controversy around Thomas and Sally began even before performances. In September, MTC’s promotional art for the play—which portrayed a smirking Sally Hemings in front of Thomas Jefferson—drew criticisms for portraying Hemings as a seductress. MTC issued an apology, took down the image online, and removed it from the show’s program. When some asked to see the script of the play, wondering if the show was going to literally romanticize the Jefferson-Hemings history, the theatre responded on Twitter with: “Don’t judge a book by its cover. My math textbook had a picture of someone enjoying themselves on it. I did not enjoy myself at all.” Critical comments were also deleted from the theatre’s Facebook page.

MTC managing director Keri Kellerman admitted later, regretfully, that such social media responses were not handled properly. “We were unprepared for the immediacy of the response, and the volume of the response,” she said. “So we just didn’t have policies in place for people to be prepared to address these issues with the right tone of voice and with the right information. And I think our initial responses came off as reactive and defensive, and that is not what we intended. I think it made the conversations more difficult.”

Another person who was surprised was Bradshaw. He had billed the work as historical fiction and intended it to be an exploration of racism past and present, as well of the hypocrisy of the Founding Fathers.

“I think the greatest misunderstanding is that I was dismissive of or indifferent to people’s protests,” Bradshaw wrote in an email. “I was very upset when I found out about people’s negative reactions to the play, before the show had opened. I thought that if people saw the play their point of view would change. I was heartened when some people came out of the play with a different experience than they had expected. I also had conversations with people who saw the show, and were still concerned by it, so that I could better understand their point of view.”

One such concerned individual was Tracy Camp, a local actor and educator. For almost every night of the run of Thomas and Sally, she’s driven 33 miles from her home in Oakland to MTC to join the protests. She initially gave MTC the benefit of the doubt, saying, “They do work by people of color, and so people in the black theatre community have a lot of respect for them.”

Though Camp never saw the play, she read an early version of the script and had many issues with the way Bradshaw, who is African-American, portrays the black women in the play. “Sally Hemings’s mother in the play, Betty, teaches Martha Jefferson about her clitoris,” she exclaimed. “So it’s like the black mammy trope—she’s the wise black woman teaching the naïve white woman about sex. That bothered me. And then of course, 15-year-old enslaved Sally Hemings enjoys getting raped by Thomas Jefferson.” One incendiary line, referenced by the protesters: “Sometimes he does this thing that he calls oral sex, which I love.”

According to Camp, voicing a common complaint of the play’s critics, Thomas and Sally “perpetuates stereotypes of black women being hypersexual. Many women aren’t believed when we report rape. Often people will say they actually wanted it and they invited it. The play is perpetuating rape culture.”

For MTC artistic director Jasson Minadakis, who directed Thomas and Sally, the show wasn’t intended to romanticize of rape, though he admitted some audience members who saw the play felt that way (there was an audience talkback every night after the show). Rather, he said, the intention was to show that someone who is raped can have complicated feelings about their rapist. One question the play asks, he said, is why Hemings didn’t escape from Jefferson while they were both in Paris, which had abolished slavery; Hemings instead returned with him to Monticello. Pacheco, the actor playing Hemings, believes the answer was a form of Stockholm Syndrome.

“To me, it’s a classic example of someone emotionally abusing someone else,” she explained. “She’s isolated from every single person in her family and doesn’t get to tell anybody is happening. For me, in the research that I’ve done and the experiences that I have, it is not difficult to find a way for this young person in this situation to think that she cares about this person.’” Pacheco added that the play is meant to be an exploration of one particular dynamic between two specific people, not a commentary on all black women.

Unfortunately, misunderstandings over the response to the play did not end with an interpretive dispute. In response to what the theatre said were threats of violence toward its staff members and the actors of Thomas and Sally, MTC hired a security guard for the run of the show. One evening, members of Regina’s Door, a local organization for survivors of human trafficking, held a vigil for Hemings in front of MTC; as the predominantly black group lit a candle and burned sage, the security guard called the local police for assistance.

“Marin Theatre Company’s two male security guards stood taunting the women performing the ritual,” Camp recounted, who was on the scene when it happened. “Marin Theatre Company’s security guards were saying things like, ‘Get a job! This is America! Be respectful!’ to these survivors of sex trafficking as they sang spirituals. These women are the modern-day version of Sally Hemings, and Marin Theatre Company called police and allowed their own security guards to taunt them.” She then added: “We all know how dangerous a call to the police can end up for black people.”

Minadakis explained that because of the fires that had been roaring that weekend in Sonoma County in Northern California, 70 miles north of Mill Valley, the open flame used to burn the sage had made security personnel nervous. “That first situation with Regina’s Door, I think we all wish had gone a different way,” he said. “Throughout the protest, we have tried to say, ‘This is an important part of this conversation, the protesters were here because they have a truth that they are speaking about this.’ We were trying to put that into context, and we were happy to put that into our conversations.”

The open letter that was later drafted called for the theatre to apologize, as well as to take some concrete actions: to diversify its predominantly white staff and to “interrogate and change your methods and processes of commissioning, developing, and producing culturally diverse work.”

The letter ended with:

This open letter serves not just as a recommendation for MTC but for other theatre companies large and small moving forward. If MTC or any theatre company across the nation wishes to create diverse works of art by telling black or POC narratives, they must take responsibility for the messages they are promoting. Any theatre institution across the nation who doesn’t have the resources to develop a piece by a person any systemically marginalized artist should deeply consider whether continuing with the production is responsible.

For Lauren Spencer, a local black actor and a member of the coalition that drafted the letter, the Thomas and Sally controversy and MTC’s response show that the theatre didn’t have the correct infrastructure in place to discuss the work with the community, especially the black community it was portraying onstage.

Spencer, who has acted in two MTC productions, suggests that the theatre “have a community liaison and cultural adviser who can reach out to the community in advance. So if you’re doing a piece that you realize might cause some controversy or tap into a specific narrative that might be sensitive, they can provide resources to support that community in processing the work, and helping you respond to any backlash. Part of the problem at MTC was the initial backlash wasn’t handled well or handled with cultural sensitivity.”

For her part, Camp would like to see MTC donate the profits from Thomas and Sally to survivors of sex trafficking. Last week, MTC and the coalition had a private meeting, and both groups plan to move forward together in addressing the concerns in the letter.

In speaking about the play, many members of the coalition emphasized that their protest is not because the theatre tackled a difficult subject matter. Their problem was mostly with the execution—though, as Victor pointed out, the problems began with Thomas and Sally’s central conceit, which seems to grant more agency to Hemings than is historically accurate. “If you look at the memoirs of Madison, Sally Hemings’s son, he talks about how she wasn’t even allowed to name him,” explained Victor. “How are you going to tell me that she has any agency over consent and sexuality when she couldn’t even name her own children?” This past summer, Sally Hemings’s quarters were uncovered at Monticello: They consisted of a small, windowless room.

Dezi Soley, who was up for the role of Hemings in the play, ultimately declined due to her objections to it. She had recently played a young slave in Bondage by Star Finch, at Alter Theater in nearby San Rafael, Calif. In it, her character was assaulted by the slave master. She contrasted that play’s portrayal of assault with Thomas and Sally.

“My character, it’s clear the discomfort, she’s scared,” Soley said of the role in Bondage. “And simultaneously you see the survival tactics that my character is using, when she chooses to smile at him, and play him a little. Then she realizes, ‘Oh shit, I’m in way too deep, I thought I had power in this situation but I don’t.’”

Soley didn’t see the same depth in the character of Hemings in Thomas and Sally. She also wonders what it says, in 2017, to portray the positive feelings that a slave might have had for her owner. “When we’re retraumatizing people, what is the point?” she posited. One good thing that has emerged from the controversy, she said, is the opening it provides for theatres to grow in a positive direction. “I do see this as a great opportunity for a whole theatre community to reevaluate our collective responsibility to the narrative that we’re telling, and to the people who are part of the communities of the stories we’re telling.”

Update: After this story was published, Marin Theatre Company released in statement that read, in part:

We have heard and respect the concerns expressed by members of The Coalition of Bay Area Black Women Theater Artists (TCBABWTC). We share a great many goals with them, including creating more welcoming and safe spaces for people of color, offering more artistic opportunities for diverse voices, and fostering a better understanding of the rights of African American women and girls.