It’s not just the South that has reckoning to do with the nation’s toxic legacy of slavery and white supremacy. Along with highly publicized reexaminations of 19th-century life at Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown University and the University of Virginia, colleges in the Ivy League—Brown University in Providence, R.I., Columbia University in New York City, and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.—have stepped up to examine in detail their historical ties to the institution of slavery.

New Jersey’s Princeton University has joined this effort, and put theatre into the mix, teaming with McCarter Theater Center, the 87-year-old resident professional company that makes its home on the college’s campus, to conduct a project that explores the university’s entanglement with slavery.

Along with a website that provides open access to documents that outline the school’s connection to slavery through ownership—the first eight presidents of the university held slaves—the university’s “2017 Princeton and Slavery Project” includes original creative work, cultivated through the collaboration with McCarter. The theatre has commissioned seven short plays that explore the history and ongoing legacy of Princeton’s participation in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

A reading of the plays, hosted by McCarter and open to the public, is scheduled for Nov. 18-19. The roster of well-known contributing playwrights includes Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Nathan Alan Davis, Jackie Sibblies Drury, Dipika Guha, Regina Taylor, and the McCarter’s artistic director, Emily Mann. The style and form of each compact 10-minute play differ widely, but all depict historical figures that played a role in intertwining Princeton with the utility and profit-making practices of the slave trade. I got a sneak peek at the plays during their initial read-though at McCarter in early September.

Research began well before that read-through. Nearly a year ago, on Nov. 11, 2016, the week of the presidential election, the participating playwrights gathered at Princeton to begin their archival digging.

“We were all just working through the numb and shock that we still felt after the election, but by the end we felt energized,” noted Mann, who has authored such historically based works as Execution of Justice, about the 1978 assassinations of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone in San Francisco, and a popular stage adaptation of Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years. Mann’s own contribution to the Princeton project, a domestic drama that takes place on the day of a campus slave auction, packs a considerable wallop.

On hand at the research gathering as lead investigator was Martha Sandweiss, a Princeton professor of history and the author of an op-ed about the project in The Nation. “History is dynamic,” Sandweiss asserted in her essay. “It is not simply what happened in the past—it’s the stories we tell about it.”

The seven plays breathe life into stories captured in the archives. They also recast Princeton as a haunted place, resonant with echoes of the past yet still full of new possibilities. The plays, Sandweiss speculated, will allow the university and members of its wider community to experience Princeton anew.

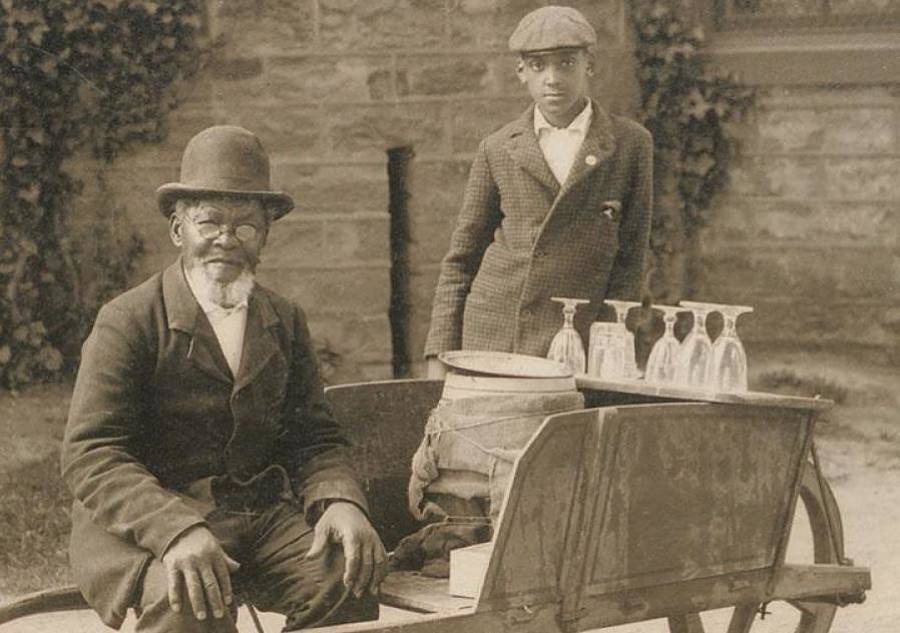

The ongoing impact of history serves as the point of departure for each play. Regina Taylor (Crowns) and Jackie Sibblies Drury (We Are Proud to Present…) both take up the story of a runaway slave from Maryland named Jim Collins, who lived in Princeton for most of his life. After fleeing his master, Collins became a janitor at the university and remained there until a student from Maryland recognized him as a runaway slave. Following the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, the police arrested Collins, but the laws of New Jersey required he have a jury trial. Although Collins asserted he was a free man, the jury sided with his former master, Teakle Wallace. Before Wallace left to take Collins back to Maryland, however, a Princeton community member purchased him from Wallace, and insisted that he repay her before she set him free. Collins never received freedom papers.

Taylor’s play depicts slavery’s perpetual costs. It uses ringing bells to transport listeners to the past, and beatboxing to propel them forward to the present. The narrative seems designed to interrupt the stability of the historical record and show its continued unfolding over time. “They buy Jim Collins back, then say that he has to repay them,” Taylor said of her protagonist in a phone interview. “He has to work off that debt, and as African Americans, we are still working off that debt.” Referring to the 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery—and the gaping “convicted of a crime” loophole detailed in Ava DuVernay’s film 13th—Taylor contends, “Parts of that slavery system are still intact.”

In her own riff on Collins’s story, Sibblies Drury takes a different approach, deploying her signature style of overlapping and competing stories. Her play begins with an extended dance sequence establishing the power a student named “White Andrew” had over Jim; the connection of these permeates the setting of the play. Like many college freshmen, Collins comes to Princeton to reinvent himself, but, because of his race and station, social structures and power dynamics won’t allow him to do so. Collins’s haunting presence, however, interferes with Andrew’s own ability to make a fresh start.

Haunting also figures prominently in the works of Nathan Alan Davis (Nat Turner in Jerusalem) and Jacobs-Jenkins (The Octoroon) as well. Alan Davis’s Afrofuturist play, his third about slavery, focuses as much on the present and the future as the past. It imagines a conversation between a college freshman, Jasmine, and a statue of John Witherspoon, the sixth president of Princeton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence as well as a slave owner. Davis has Witherspoon come alive as Jasmine tries to destroy the statue with a blowtorch. The uproarious dialogue, augmented by Jasmine’s hip-hop-inflected voice and Witherspoon’s grandiosity, demonstrates, as Davis put it to me, that “the mistake we often make in talking about history is looking at it as a thing that doesn’t affect us, that is totally separate from us. The reality is that history is living inside all of us and we haven’t fully come to terms with it.”

Like Taylor, Davis also makes reference to contemporary policing, drawing attention to the relationship between the history of slavery and current structures of law enforcement.

Not all the ghosts unleashed by the “Princeton and Slavery Project” are frightening. Jacobs-Jenkins’s play follows two college roommates back in time via a séance, where they meet a beautiful woman named Analise at a party. The roommates have sexual escapades on their minds, but Analise has another idea: She wants to commune with the dead. One roommate finds himself in a drunken conversation with Betsey Stockton, the former slave of Robert Stockton, a senator from New Jersey. (Stockton is the great-grandson of John Stockton, who donated the land that made it possible to move Princeton University from its original location in Newark to its current campus.) Coupling geographic and time travel, the play emphasizes the importance of circulating the stories of people of color.

The project also mines the international history of slavery, and how Princeton University’s involvement in the trade established it in both global and local economies. The contributions of Kwei-Armah and Guha focus on the American Colonization Society (ACS), founded in Princeton in 1816. Guha noted that at the first writers’ meeting, adviser Sandweiss brought up the topic of ACS right away. “I had no idea that America had its own explicit project about colonization, or that it had to do with the repatriation of freed former slaves to Africa, a continent they’d never set foot on,” Guha noted.

As the playwrights learned, the trans-Atlantic circuits of exchange flowed in many directions, and included efforts to send formerly enslaved people back to Africa. As Kwei-Armah, who is scheduled to leave his position as artistic leader of Baltimore Center Stage at the end of the 2017-18 season, put it in a telephone interview, “Trans-Atlantic slavery was globalization at its most manifest.”

His and other plays in the project show how the impact of slavery seeped into every aspect of 19th-century life. In Mann’s drama, a slave auction takes place on the Princeton campus in front of the college president’s house, where a stand of trees called the “liberty trees” still grow today. In preparation for the sale, an enslaved man has a conversation with his son about freedom; many participants in the rehearsal room commented on how the speech reminded them of contemporary conversations about racial violence. “All history plays are really about the present,” Mann said. “I felt compelled to tell that story because it means something now.”

Mann’s comments came just days before white supremacist violence burst onto University of Virginia’s community in Charlottesville, Va., demonstrating anew that the legacy of slavery still shapes U.S. communities in profound ways. The “Princeton and Slavery Project” sets out to harness the power of art to expand what we know about familiar parts of our world, the places we call home—and asks that we look at these places again with fresh eyes.

“You look at many of the Greek works, and your hero is always trying to find his way home,” Kwei-Armah concluded. “I feel, as a diasporic African, that art is my tool to find my way home.”

Soyica Colbert is an associate professor of African-American Studies and chair of the Department of Performing Arts at Georgetown University.