O, yes, I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be.

—Langston Hughes

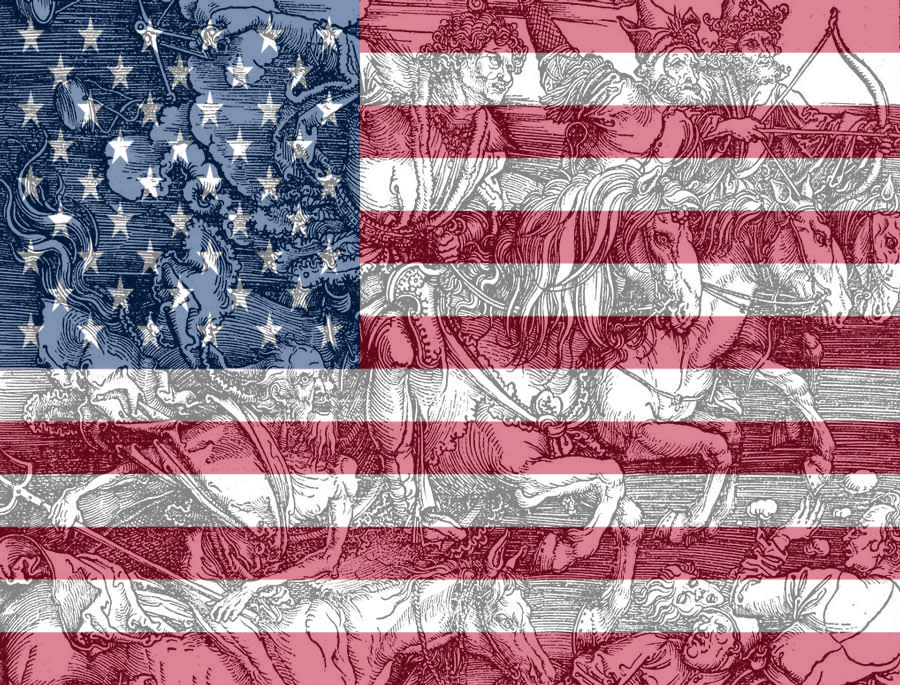

In Albrecht Dürer’s 1497 woodcut, four horsemen representing Conquest, War, Famine, and Death are galloping toward us, determined to slaughter all those who stand before them. Their horses crush under their hooves anybody who stands in their way. This work, a dramatically distilled version of the passage from the Book of Revelation, is one of the most potent visual representations of apocalypse ever to appear before our eyes.

That is, it would seem, until Donald Trump stepped onto the stage as our 45th president. And yet the image of Trump, and the obsessive focus on the archvillain himself, on his personality, distracts us from the truth of how we got here. And in doing so, we obscure the means to get out of here and make real change.

Trump is not an aberration, an abnormality, a sinkhole that has mysteriously opened up within our democracy. As playwright and essayist John Steppling writes, “Trump is the logical culmination of the rightward drift of U.S. liberalism over the last 50 years. He is the sun-lamped face of capital.”

While civil liberties and human rights are suffering further setbacks under the Trump presidency, those people and topics that were already criminalized and censored will now be doubly so. However, instead of seeing the cyber-shenanigans of a foreign power as the main problem, or rallying to the defense of a standard neoliberal agenda as the solution, we in the theatre community should dig for and expose the deeper structural problems at the root of our malaise. We must embrace the opportunity to use our work, spaces, bodies, and voices to engage in the aesthetics and politics of true empathy and resistance to injustice in all its forms.

The heads of the mainstream televised “resistance” to Trump do not represent a way forward, despite the noise they are able to generate in the media. This “resistance,” which is largely spearheaded by an elite within the Democratic Party, remains mostly silent about the burning questions of our time—and it is most certainly not concerned with what Martin Luther King Jr. identified 50 years ago as the triple evils, or “giant triplets,” of racism, militarism, and economic exploitation, or “extreme materialism.” For the most part, this “resistance” does not move against continued mass incarceration, police brutality, or the erosion civil liberties, not to mention systemic racial inequality and environmental destruction. Its leaders do not speak to the madness of the more than 800 U.S. military bases straddling the globe, the bloated military budget, or the influence of the arms industry on politics.

We cannot look to them to condemn the massive body counts of Arab and Muslim civilians racked up during our endless wars, many of which were fought at their behest and at great profit to them and their benefactors. Nor, quite predictably, does this so-called resistance utter a word about U.S.-backed apartheid in Palestine or other loathsome U.S.-backed regimes, in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

We would argue, therefore, that this is a moment to reject the lure of the mainstream anti-Trump wave, and instead to step back and realize that much of American history has in reality been the age of Trump in one way or another, especially for the most marginalized. That is the story.

Yes, Trump personifies—aesthetically, professionally, and morally—the tackiest sort of charlatanism. But he’s nothing new: he’s a figure straight out of Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class. What if the actual reason Trump is so scary to the mainstream media, to Democratic politicians and liberal institutions, is precisely because he exposes what they have so diligently covered up, talked around, and band-aided away for decades—namely, the profoundly violent and racist nature of the United States since its founding? Seen this way, to claim to be in opposition to Trump and “Trumpism” without recognizing and opposing the larger, longstanding, entrenched structures of American violence and inequality, we are in fact aiding and abetting this willed myopia. Our cultural and political elite are and have long been complicit in this sordid project, even if at times unwittingly.

“Every single empire,” wrote Edward Said, “in its official discourse has said that it is not like all the others, that its circumstances are special, that it has a mission to enlighten, civilize, bring order and democracy, and that it uses force only as a last resort. And, sadder still, there always is a chorus of willing intellectuals to say calming words about benign or altruistic empires, as if one shouldn’t trust the evidence of one’s eyes watching the destruction and the misery and death brought by the latest ‘mission civilisatrice’.”

Since WWII the U.S. has intervened in and bombed more than 70 countries. We are talking about millions of deaths (3 million in Vietnam alone), and most of them civilians. In 2015, Physicians for Social Responsibility released a report estimating 1.3 million deaths as a result of the “War on Terror” in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, between 2001 and 2013. This staggering figure does not include the more than 10,000 dead in Yemen as a result of U.S. drone strikes, as well as the subsequent and ongoing U.S.-backed Saudi air war against the impoverished nation of 27 million. Nor does this number include the deaths of Iraqi civilians as a result of the first Gulf War and U.S. sanctions of the 1990s (the latter the handiwork of a Democratic administration), which would add nearly a million more deaths to the already grisly calculus of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East over the last quarter of a century. To focus solely on Trump’s daily antics, then, is to make invisible this wake of death not only trailing behind us, but pooling at our feet.

As writers we believe it is imperative to hold this brutal history alive within this present moment in which we create, and not lose sight of what it really means to be American, or at least what it means to live in an age of American power. In so doing, we must always locate ourselves in relation to white supremacy and empire. This might mean, in the words of the Federation of Artists Manifesto issued by the Paris Commune in April 1871, working “cooperatively toward our regeneration, the birth of communal luxury, future splendors and the Universal Republic.”

This would also mean decentralizing the flow of history, reimagining and foregrounding an America that defies empire. In this spirit we can challenge ourselves to create a stage that is welcoming to those who have the most to teach us: the marginalized, the targeted, the undocumented. Surely it is in these often neglected communities and spaces, where dissent is not only at its most lucid in its understanding of the aforementioned structures of violence and bigotry, but also the most courageous and creative in its modes of opposition. It is to these communities we must look for a new aesthetics of defiance and useful tactics for holistic dissent and action.

However, many voices challenging the system in its entirety are censored by mainstream media, including the theatre and film industries. This censorship also happens through economic oppression and deprivation, which leads to everything from the underfunding of our less commercially oriented theatres to the defunding our educational system, our public spaces, our libraries, and our independent artists, journalists, and thinkers. To believe that our theatre is without censorship is a dangerous misconception, and typical of the self-congratulatory liberal politics that has gripped us in recent years, but especially over the past 12 months. The topic of Palestine is just one example of such censorship, whether onstage, on campuses, or in the media. And it’s stubbornly persistent: In 1989, Joseph Papp, under pressure from his board, canceled the El-Hakawati Palestinian theatre production at the Public Theater. Twenty-seven years later, the Public again canceled a Palestinian production, The Siege, from the Jenin Freedom Theater. Even more recently, the Public canceled the English-language world premiere of our adaptation of Ghassan Kanafani’s novel Returning to Haifa—a project the theatre had itself commissioned, and that its artistic director, Oskar Eustis, was set to direct. And while this “Palestine exception to free speech” is in some ways an anomaly, in other ways it is a bellwether, a dangerous precedent and a blueprint for just how easy it is to silence dissent and chill free speech, even in broad daylight.

So what stories do we bring to the stage? Whose histories? How do we stop chattering about Trump and instead listen to the reservations, the ghettos and prisons, the gutted corners and corridors of the United States, and to the bombed and besieged periphery of empire, where the laboratories of the arms and “security” industries are located, from places like Pine Ridge to Gaza to Ferguson? As activist and scholar Angela Davis reminds us, “Justice must be everywhere and always indivisible.” In our work for the stage, do we perpetuate stereotypes, perhaps even unwittingly, in the service of the status quo? Young playwrights are still too often encouraged to peer inside themselves for stories, to explore domesticity, often under the guise of tackling controversial topics. Antonin Artaud’s searing critique of theatre in the 1930s is still relevant today: “Given the theatre as we see it here, one would say there is nothing more to life than knowing…how we cope with our little pangs of conscience, and whether we will become conscious of our ‘complexes’ or if indeed our complexes will do us in. Rarely, moreover, does the debate rise to a social level, rarely do we question our social and moral system.”

Our moral system, from our health and “justice system” to our country’s involvement in Conquest, War, Famine, and Death are not dry political topics—grist for the dreaded “issues” play—that we must engage with onstage only in these more obvious Trump Times. Rather these phenomena are the very stuff of which drama is made, the meat and bread of our shared tragedies and in turn our common humanity. As playwrights, diving into these wrecks of human histories is to discover not despair but hope. It is to encounter creativity, wild visions and vivid dreams of another way of being, living, and dying. To appropriate Peter Kropotkin’s vision, theatre should seek “to extend itself to universalize itself . . . In place of communal privileges it has to put human solidarity.”

We must, therefore, break through the conventional thinking that corrodes our abilities as writers to see what is real. As the black surrealist from Martinique, Jules Monnerot, writes: “Conventional thinking corrodes slowly even the most rigorous concepts circulating like blood, and thanks to this the poison of conventional thinking becomes permanent and definite.” Monnerot calls for “a dialectical reinvention of magic”—real magic that makes real alternatives to racialized capitalism, a modern world system, according to Cedric Robinson, that evolved from and is dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism, and genocide. Art, Eduardo Galeano reminds us, has the power to “express the magical reality at the core of the hideous reality of the world.”

To achieve this alchemy in our lives and work, we must know what we are for as well as what we are against, to turn our holistic (as opposed to compartmentalized) dissent into intertwining visions for the future. This requires real alliances based on radical empathy, solidarity, reciprocity. If we have not already, let us learn hard and deep the necessary strategies from America’s black radical tradition, not to appropriate or replicate it but to understand its logic and fundamental demand: a complete critique of Western civilization and, as Franz Fanon put it, a disordering of our current (colonial) social order. Let us study and embrace the Movement for Black Lives platform, a coalition of 60 different organizations, an ambitious, ever-evolving map for today’s political and cultural resistance, including our theatres and stages. As the historian Robin D.G. Kelley writes: “‘A Vision for Black Lives’ is less a political platform than a plan for ending structural racism, saving the planet, and transforming the entire nation—not just black lives.” By decentering the conformist surge we have a better chance of resisting the system rather than getting stuck in the Slough of Despond facing the hideous Apollyon. “The best of our struggles,” Kelley maintains, “ are not reactions to misery but quests for freedom.”

Creating itself is a quest for freedom. We can fire up our imaginations through learning about and supporting such organizations as the Black Youth Project 100, Million Hoodies, Black Alliance for Just Immigration, Dream Defenders, the Organization for Black Struggle, Southerners on New Ground (SONG), LEAP, and many others. For those of us who are white, we might also join SURJ, a national network of groups and individuals organizing white people for racial justice. We can also find inspiration with the Water Protectors at Standing Rock, indigenous communities that have been at the forefront of protecting our natural world; with queer rights workers, with immigrant rights workers, and with the decades long Palestinian non-violent movement for liberation, including but not limited to the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement.

And while we call on ourselves to put banished, buried histories of conflict and resistance onto our center stages, let us not forget those who have been carrying the torch for decades, writing vital, dangerous theatre. We theatre artists have a rich history to draw upon. Writers, directors, alternative and/or radical theatre spaces have been facing down the horsemen of the apocalypse for decades now, prying open the elite doors of mainstream theatre, making them a little wider for others traditionally unwelcomed to the stage. We have a wealth of theatre artists who engage with what Henry Giroux calls the “pedagogies of repression,” usurping the “dead zones of the imagination” to give us glimpses of other possibilities than a culture addicted to consumerism, war, and self-aggrandizement. And as we create our inventive, subversive, ever-changing maps of resistance and possibility for the stage, we might well remember the words the South African artist Thuli Gamedze used to describe the black imagination—words which lend themselves to the kind of theatre we might aspire to, a theatre of “improvisation, a dance in an obstacle course, a performance inside a burning room. It is impermanent and has no binaries to hide behind.”

As theatre folk, we can and must strive to create a multiracial, cross-class movement that centers people of color’s leadership to subvert the status quo workings of our theatre world (and not just by achieving diversity quotas in casting, for instance). U.S. theatre is overwhelmingly, at times blindingly, white, not only in terms of who makes decisions and who fills the (generally very expensive) seats, but in its core politics and worldview. How can we circumvent the gatekeepers and subvert, or at least redefine, the insitutions they run? It is a tall order, but within our imaginations and collaborations are charts to guide us. We are, after all, storytellers. Who said we cannot write the story of a future that is for and by us? As Ursula K. Le Guin reminds us, “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable—but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.”

So, yes, the horsemen of the apocalypse are still riding, and surely they are terrifying to behold. But rather than allow ourselves to become entranced by their spectacle, let us ask instead: Who stabled their horses before they rode out into the night? Who gave the horsemen shelter and food before they mounted? To answer these questions, we must become critical thinkers and writers, undermining the systems of power that diminish our lives, that diminish our ancestors as well as generations to follow. As Giroux suggests, such critical thinking “is the precondition for nurturing the ethical imagination that enables engaged citizens to learn how to govern rather than be governed.”

When perhaps our most brilliant critic of American history, W.E.B. Du Bois, turned 93, he wrote: “Today I have reached my conclusion: Capitalism cannot reform itself; it is doomed to self-destruction.” Du Bois knew that racial capitalism was the true recurring apocalypse and that we would need all of our bodies and creative capacities to oppose it. And on these ever expanding, inspiring and electric stages, we will surely find, as he promises, space to stretch our arms and souls, “the right to breathe…thinking, dreaming, working as (we) will in a kingdom of beauty and love.”

Playwrights Naomi Wallace and Ismail Khalidi are frequent collaborators. For more about the authors, go here.

An incomplete list of these playwrights includes: Lorraine Hansberry, Langston Hughes, Adrienne Kennedy, Kia Corthron, David Henry Hwang, Roger Guenveur Smith, William S. Yellow Robe Jr., and George C. Wolfe. And more recently Kwame Kwei-Armah, George Brant, Branden Jacob-Jenkins, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Lisa B. Thompson, Stephen Orlov, Tanya Barfield, Caridad Svich, Tanya Saracho, Taylor Mac, Yussef El Guindi, Betty Shamieh, and Young Jean Lee. And let us continue to support and encourage our fearless younger writers: Jackie Sibblies Drury, Kara Lee Corthron, MJ Kaufman, Hanah Khalil, Fernanda Coppel, Elizabeth Irwin, Andrew Saito, and Aeneas Hemphill.