On October 17, 1967, Hair premiered at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater in downtown New York City; the first production to open at that new year-round space. The assistant director on this self-described “American tribal love-rock musical,” with book and lyrics by James Rado and Gerome Ragni and music by Galt MacDermot, was 21-year-old Amy Saltz. She looks back on how the pieces all came together to make an unlikely hit.

All of us who worked at the New York Shakespeare Festival during the summer of 1967 knew about the new rock musical that would open the brand new Public Theater in the fall. We had seen James Rado and Gerry Ragni at the Delacorte, escorted through the backstage area by director Gerald Freedman during an intermission of a Shakespeare in the Park production of Titus Andronicus (with Olympia Dukakis, Charles Durning, Moses Gunn, and Raul Julia) that Gerald had directed. Rado and Ragni were in their youthful ’30s, Jimmy’s hair blond and straight, Gerry’s styled in a big Afro. They seemed to be taken with the magic of the setting, the set and stage lights at night against the background of the moon, Belvedere Castle, and the lights of Fifth Avenue in the distance. Their long hair and “cool” manner had the backstage buzzing.

Their new “love-rock musical” was to be the first production at the brand new Public Theater. The indomitable Joseph Papp had convinced New York City to rent him the old Astor Library on Lafayette St. for $1 a year for 25 years. He wanted to produce primarily new work year-round. The once-magnificent old building, which had been built by John Jacob Astor and was among the city’s first public libraries, had fallen on hard times and was in a sad condition. It was being renovated during the summer of 1967, and the new multi-theatre complex would open in the fall. The price of admission would be $2.50. Really!

We had rehearsed productions for that summer season in what was then a vast, bare-bones space on the third floor of that old library, to be called Martinson Hall. Hair would be the first production of a multi-play season at the Public Theater, and would be performed in the complex’s biggest space, the Anspacher, which was the first theatre to be built.

When Hair started rehearsals, the Anspacher wasn’t finished. In fact, the build was slower than anticipated, and they were behind schedule. The stage area was still a big hole in the ground. No one could be certain that it would be finished in time for opening night. Many—if not all—of us checked the progress day by day.

I remember a late-night car ride one balmy night early that summer with Marty Aronstein, the lighting designer for the Park (who would also design at the Public), his assistant Larry Metzler, Steve Shaw (who was prop master for both), and myself. Marty asked if anyone had seen the script for this “new musical.” Steve had. “How is it?” Marty asked.

“How would I know?” responded Steve. “The lyrics are like…‘I got my arms I got my toes I got my mouth.’ What can you tell from that?” We all laughed, our curiosity not in the least bit assuaged.

It was in large part because of Gerald “Jerry” Freedman, artistic director of New York Shakespeare Festival, and his musical director, John Morris, that Joe produced Hair. It was a nonlinear anti-war play about young people and the draft. Its music was the music of young people: rock. It was composed by the hugely talented Galt McDermot. No one had done a rock musical before, and it was questionable how a theatregoing audience would respond. It was a far cry from I Do! I Do! or Cabaret. The script needed development. The writers were the first to admit that they were very much “in process.” Joe was ambivalent. Jerry and John pushed hard. Eventually Joe gave in.

Jerry, who was slated to direct the show at the Public, worked with the writers to shape and develop the script. Anna Sokolow, one of the top modern choreographers, was brought in for the dances. The estimable Ming Cho Lee would design the sets. Theoni Aldredge would design the costumes, Marty Aronstein the lights. This threesome had designed most of the productions at the Delacorte and were a formidable team.

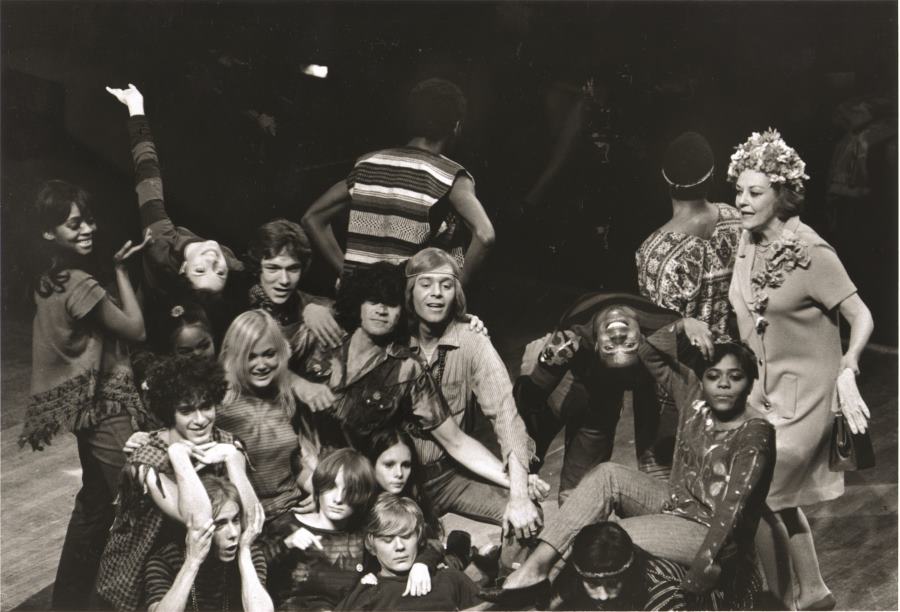

Auditions were held. A wide search was on for talented young people who could sing and act and tell this story. They came from all over the city. Ultimately the youngest cast members were three talented 16-year-olds who were all in high school together in Brooklyn. Most of the others weren’t much older. Many had not previously been in a professional production. They would need to be taught professional etiquette: to be on time for rehearsals, to make entrances on time, not to smoke dope in rehearsal, etc. There were only two adults, Ed Crowley and Marijane Maricle. They both had good senses of humor and were game. After the production at the Public and at Cheetah, the midtown nightclub where it ran briefly at the end of the year, the high schoolers and some of the other “kids” went on to the eventual Broadway production.

Just before rehearsals started, Anna had an appendicitis attack and needed surgery. Hair went into rehearsals minus a choreographer or a finished theatre.

A couple of summers before, I had dropped out of college for a semester, and miraculously got my dream job as an intern (a gofer, to be precise) at the Shakespeare Festival. I brought water (much needed on hot days outdoors under the sun at the Delacorte) and coffee. (There was no backstage coffee pot at the Delacorte in those days. I had to go to the Excelsior Coffee Shop on Amsterdam Avenue and carry back 20 or 30 cups of coffee—tricky!) I called “5 minutes” and “places” in various locations that had no intercom, and eventually ran the stage right prop box during performance. That summer I stood backstage as James Earl Jones played Othello and Julie Harris played Ophelia. I felt like the luckiest gal in the world.

The next summer I was promoted to assistant stage manager. Again, I was in my glory. When it was time to open the Public, I was asked to come downtown as assistant stage manager. I was young and a dreamer. I wanted to be a director and was afraid that if I kept stage managing I wouldn’t direct (“A dream deferred…”). So I said no, thereby turning down a plum job. I was sorry to be missing the opportunity of working at the Public (actually opening the Public!) and nervously hoped that I was making the right decision.

A couple of days after Hair went into rehearsal, I got a phone call from Rusty McGrath, the festival’s production stage manager. He said that Jerry needed an assistant and wanted to know if I’d be interested. I’d be paid $25 a week, which would barely cover car fare. Of course I leapt! That first day I was to meet Jerry in the green room behind the Anspacher. I’d be given a script when I got there, and the mystery of what this play actually was would be revealed. I was nervous and excited.

When I walked into the green room my heart stopped. A 20ish-year-old woman with a huge voice was standing in the middle of the room belting out “Dead End.” I would learn that this was Jill O’Hara, who was playing Sheila. A very proper, short-haired gentleman (not often seen around the Public in those days) wearing an Oxford-type shirt was at the piano: Galt McDermott. This was a music rehearsal. Some cast members sat around on the floor. They were so young! There were a couple of older folks, but most of the cast seemed like babies—even to me, at a ripe age of 21.

As the days went by and Anna Sokolow was slowly recovering from her appendectomy, Jerry improvised movement for the musical numbers.

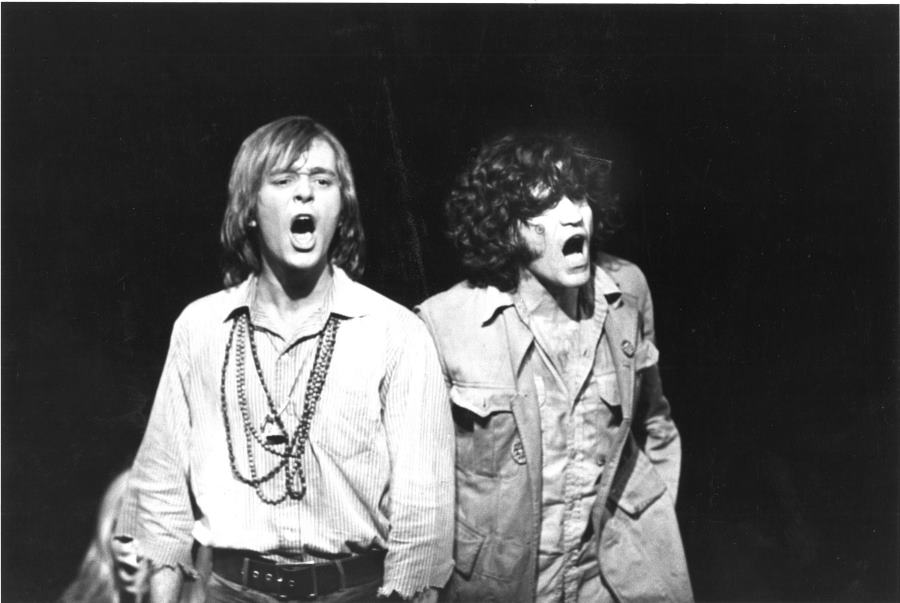

Meanwhile, the theatre was coming along. Once the floor was in, we started to rehearse there. One of the first rehearsals was for the song, “Aquarius.” Jerry asked everyone to lie on the floor, touching. The cast was to sing a cappella. The lights were turned off. We waited in silence for a long time. Then it started. A single voice in the dark: “When the moon is in the seventh house….” Soon the others joined in. The gorgeous voices lifted into the huge space as if baptizing it.

Soon the smell of marijuana came wafting through the air. The cast was passing a joint around as they lay on the floor in the dark room. The lights were turned back on. The young performers were reminded that smoking weed in the middle of rehearsal was a no-no. Rehearsal continued with the lights on.

When Anna finally came back to the show, she was still in substantial pain and was having trouble walking. We rehearsed in the theatre, Anna sitting in the first row, short and authoritative. She had missed 10 days of rehearsal and so had missed the discoveries that had been made during that time as the show developed, grew, and changed. She was a strong, willful woman—hugely creative, hugely successful—and accustomed to running her own modern dance company with an iron fist. As she worked, it became clear that her choreography did not blend with the work that Jerry was doing. He wanted movement that would seem to grow organically from the young folks, but Anna was a modern dance choreographer with an entirely different style. Tension began to develop. If one of them turned down a request or suggestion from Rado or Ragni, the authors would go to the other and ask for the same thing.

Soon the artistic differences were getting in the way of the work. We were a week or 10 days from the first preview when Jerry decided that it would be in the best interests of the production for him to resign from the show and let Anna take over.

Anna added substantial choreography to the musical; it soon became a dance-theatre piece. She fired the actor who was playing Claude and replaced him with James Rado. And she veered from the text: It wasn’t unusual for her to choreograph something that was in direct opposition to a line in the script. A young actress refused to do something that Anna wanted her to do and was fired on the spot.

On a break late one afternoon, Anna stood at her front row seat with Joe Papp next to her. They were talking about the show. Tony and Miranda, Joe’s young children, were chasing each other around the theatre, their voices raised. Anna grew impatient. “Get those children out of this theatre,” she demanded.

Joe’s response: “This theatre took those kid’s father away. The least I can do is let them play in it.”

The day before the first preview, Joe asked Jerry to came to a dress rehearsal. Afterward there was a meeting. The next day Anna was gone and Jerry was back. The actors who had been fired were brought back. We had a five-hour rehearsal before that night’s preview. Jerry restored his staging for the first act, including the improvised movement for the musical numbers. That first preview performance was performed with Jerry’s first act staging and Anna’s second act staging. The next afternoon Jerry restored his staging for Act II. The rest of the preview period was spent honing this version of Hair.

The reviews were mostly (though not completely) positive. But audiences loved the show and word spread. Hair was attracting a new audience of young people as well as an older general theatregoing crowd. Young people went to see it because they saw themselves reflected onstage. Older people went to see it to empathize or in order to understand the younger generation, often their own kids. In short, it was selling out.

Joe wanted to extend the run of the show at the Public but the next play in the season was due to open and there was still only one theatre completed. So Joe joined forces with Michael Butler, a producer from Chicago, and moved the play to the Cheetah, a disco on 53rd Street and Broadway. Hair would perform at 7:30 p.m. on a stage in the middle of the huge hall, with audience surrounding it. When the performance was over and the audience departed, the stage would be taken down and the space would again become a dance floor.

We had four days of rehearsal to do the transition. Jerry was already in rehearsal for another production. There was also a new Sheila, who I rehearsed into the show. The rest of the cast and musicians remained the same. Rado, Ragni, and Galt had written new songs they wanted to put into the show, but there was no time to work them in.

The show ran at Cheetah for a couple of months. Then it moved to Broadway with Tom O’Horgan directing and Michael Butler producing. The rest, as they say, is theatre history. Soon, you didn’t have to go to the theatre to hear “Let the Sun Shine In.” It was wafting over the radio waves.

Hair was the first production that Joe produced with living authors. The contract didn’t cover future productions, so the Public never made much money off of Hair. That would change with other authors and future contracts at the Public.

The version that played at the Public and at Cheetah didn’t have the psychedelic lure of the Broadway production, but it had great heart and of course the terrific music. It was a play about lost kids in the midst of the Vietnam War. The draft loomed over their world and most were terrified and lonel

y. A lovely sequence was developed for “Good Morning Starshine”: By the end of the song, dawn was breaking, and each of these lost young people was reaching out for someone who was already reaching out for someone else. It was filled with yearning and spoke volumes about their vulnerability. That epitomized what the production was about: It was an anti-war play about the young people who were being asked to fight it.

No one involved at the time had any idea of the impact that both Hair and the Public Theater would have on future generations. A group of “true believers,” passionate, dedicated, and talented, made both happen. Many people were involved, some recognized, most not. Not just Joe and Jerry, Rado, Ragni, and Galt; not just Bernie Gersten, the associate producer of the Public, and John Morris, musical director. But also designers and their assistants, the cast, the musicians, stage managers Rusty McGrath and assistant David Smith, the prop department (Steve Shaw and assistant Diana Kerew), Milo Morrow and his costume department, the backstage crew headed by production manager Andy Mihok, casting director Dolores Pigott, press agent Merle Dubusky, and old Abe, who guarded the door of the Public.

As with every show, there was sweat and blood, joy and pain, discoveries and losses. It is all part of the sawdust we live and breathe. Every once in a while we work on something that ends up living on for a long time, that impacts lives in ways we never imagined or could only dream of when we started. That’s true of Hair, and it’s true of the Public Theater. And it’s true for the new generations of “true believers” fighting hard today to make their dreams come true. May the sun keep shining in.

Amy Saltz is an award-winning director based in NYC. She has worked with August Wilson (Fences and Seven Guitars), Robert Schenkkan (Lewis and Clark Reach the Euphrates), John Patrick Shanley (Danny and the Deep Blue Sea), and many others. She is Professor Emeritus at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University.