Every summer the medieval-looking city of Edinburgh transforms into the largest arts festival in the world. The Edinburgh Festival Fringe, or simply the “Fringe,” celebrated its 70th birthday this year, and as if trying to prove its own vitality, offered a record number of shows—more than 3,000—at approximately 300 venues in and around the city. A festival that large does not easily conform to a single identity. And, indeed, the Fringe does not. Visitors this year could choose from dramatic monologues, circus acts, physical theatre, immersive theatre, musicals, a plethora of comedy sketch shows and stand-up routines, and many, many other styles of performance, mounted by companies from around the world.

I was one of those visitors. This was my third Fringe in five years, and as I sat in a pub that first night, thumbing my way through the festival’s half-inch-thick official program, a valuable lesson learned from Fringes past came racing back to memory: Let the “FOMO” (fear of missing out) go. It would be impossible to see everything, so best not even to try. Instead I began making a plan I would keep to as best I could, knowing full well that any plan, no matter how well-organized, would inevitably be altered by show cancellations, inaccurate run times, and more pleasantly, last-minute recommendations and other moments of serendipity.

Case in point: As I tried to decide what to see first, I overheard a nearby couple describing a cabaret show they’d caught the night before. Its title, Mein Camp, suggested an hour of cringeworthy, un-PC puns, but the sheer delight the couple radiated while remembering their favorite lines won me over. I bought tickets, and I’m so glad I did.

Matt Gilbertson, an actor from Adelaide, South Australia, starred as “Hans,” a glammy Berliner dressed in fishnets. With a faux-German accent, he sang, tap-danced, and played the accordion over the course of what proved to be an hour-long celebration of glitter and cultural difference. His crowd work—some of the best I’ve ever seen—was as compassionate as it was funny: He called a white man in the audience with shoulder-length hair “Jesus” and asked why he wasn’t doing more to “save us” from Trump. Then, to a couple of young boys in the front row (16 and 18 years old, respectively), he apologized on behalf of grown-ups the world over for the wars and for climate change. The audience loved it.

“It’s very difficult to find what’s funny in this current moment,” Matt confessed to me later in a brief interview. On the other hand, he added, “There is so much to make fun of. Some people like their cabaret to really hammer the political message home in a very dark and heavy way. I think it can be just as powerful to discuss issues while making people laugh.”

My third Fringe was off to a great start.

I knew from previous experience that I had lucked out with Mein Camp—few shows I’ve walked into blind have ever matched its level of wit. So on day two I did some advance research. Reviews in the performers’ hometown newspapers were easy to find online, but even more helpful were the daily reviews in Edinburgh’s local paper, The Scotsman. No one should rely solely on reviews to pick shows, of course, but when you’re lost in an ocean of 3,000 choices, they serve as a sanity-saving buoy until you can find your sea legs. Another tip: Buy tickets to your top three or four choices as far in advance as possible. Well-reviewed shows tend to sell out quickly.

I wasn’t fast enough for some, but I got lucky with The Dreamer. It had received rave reviews by time I bought tickets, but I was able to snag one. Co-produced by the physical theatre company Gecko and the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, and directed by Rich Rusk, this gorgeous tour de force of physical movement and heightened emotional drama drew from the work of two playwrights celebrating their 400th anniversaries this year: William Shakespeare and the Chinese playwright Tang Xianzu. The show, inspired by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Xianzu’s The Peony Pavilion, followed a young woman named Helena (Yang Zi Yi) as she struggled to break free from her parents’ overbearing influence. A clutch of invisible tricksters drag her to and from a dreamlike world, helping her to grow into her own and eventually find love. The set featured a combination of industrial scaffolding and mobile set pieces, and the sound design was masterful: all clangs and horror music one moment and soft, mournful melodies the next.

The Dreamer benefited from an experienced director who greatly admires Shakespeare and who’s sensitive to cross-cultural interpretations of Chinese plays. Rusk saw parallels between Helena, “one of Shakespeare’s best characters,” and “leftover women,” a derogatory term sometimes used in China to describe unmarried women in their late twenties. Those women, Rusk said, “defined themselves through their relationships rather than their personal qualities.”

After the show I found myself thinking about international theatre in more expansive ways—how a synthesis of Western and Eastern traditions might produce even more inventive styles of performance. Unfortunately, though artists from around the world convened at the festival, some had a much harder time getting there.

The Arab Arts Focus (AAF) began in 2014 as a program of performances held at Cairo’s annual Downtown Contemporary Arts Festival. Curated by playwright and director Ahmed El Attar, the AAF sought to bring together artists from nations throughout the Arab world. The program was a success from the beginning, each year attracting artists from six continents.

This year, they decided for the first time to bring their programming to the Fringe. One attraction was Chill Habibi, their nightly cabaret. It featured short snippets of shows on the AAF bill and offered audiences a chance to chat with some of the artists afterward on their process, and also their struggles. The night I went, the emcee, Sara Shaarawi, explained that many of AAF’s artists and production team members (including their technical director) had not been able to secure visas to enter the U.K., with a devastating effect on the artists who did manage to make it in (some of whom had to apply multiple times). Minus crucial collaborators, many of these artists were forced to improvise both their content and their tech. Egyptian choreographer Shaymaa Shoukry had to re-choreograph her dance piece, The Resilience of the Body, just days before it opened. The Elephant, Your Majesty!, a show by a Syrian refugee, was cancelled altogether.

In an interview a few days later, Shaarawi, who was also AAF’s production coordinator for the Fringe, expressed hurt and deep frustration with the situation, which to her reeked of xenophobia.

“The Arab world is a challenging place to make art,” she explained. “We have big censorship problems, and at times it can even be dangerous to do the work we do. So it’s infuriating and appalling that a country that prides itself on being ‘civilized’ and ‘free’ would put similar limitations on those artists. We knew we would have some problems, but we never thought it would be anywhere near this blatant and this bad.”

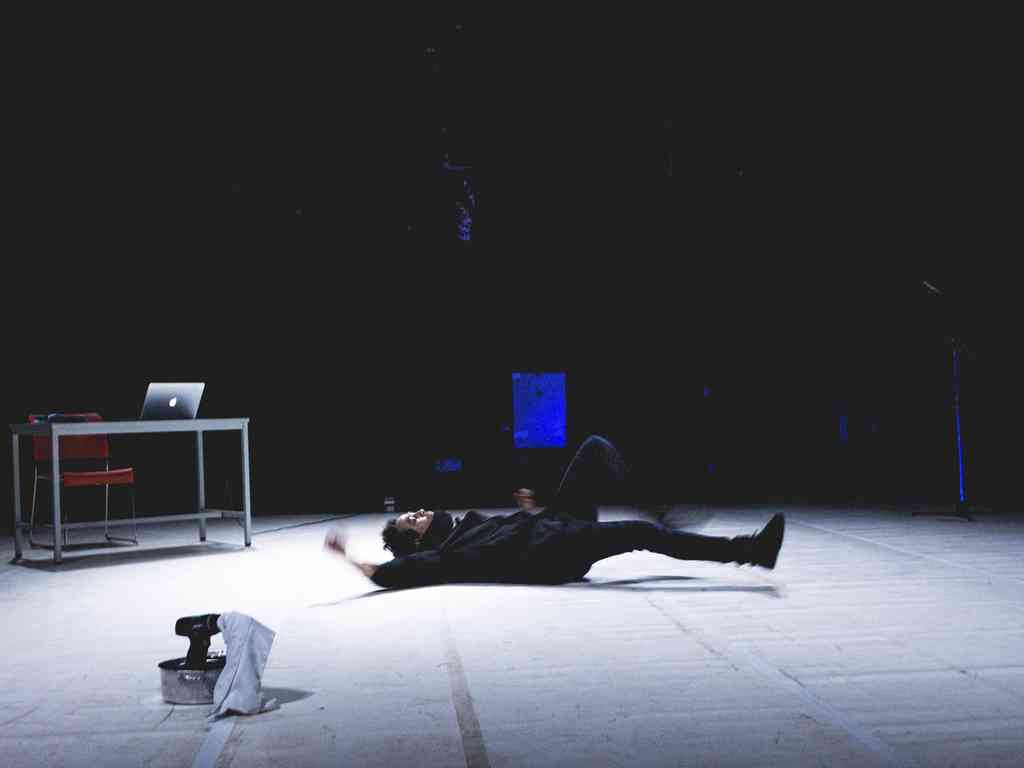

One AAF artist whose work was not compromised was Moroccan theatremaker Youness Atbane. I caught his show, The Second Copy: 2045, on my last day. It opened with the actor curled on the floor, the room dark except for a beam of projected blue light on the back wall. He slowly unfurled his body, his movements jagged as if he were struggling to control his limbs. Once he was upright the show jolted into something else entirely: a kind of mock documentary, or “lecture performance,” as he calls it, of what contemporary art might look like to future Moroccans. I won’t spoil how he connects the opening dance to the lecture segment, but I will say that the ending not only coheres—it astonishes.

The piece was born, Atbane told me later, out of a need to articulate how Moroccan politics was affecting the country’s arts. Morocco offers more artistic freedom than most Arab nations; a constitutional referendum in 2011 granted artists more freedom than ever to express their individual ideologies. But Moroccan leaders still enforce restrictions, without consistency or transparency, on what artists can produce.

“In Morocco we have a small community of contemporary artists who have been vital for the last 15 years,” Atbane said. “But because of the country’s recent political situation, we began to develop interests in how [those political] forces were affecting our country and our work. The question of how and why these forces were affecting us was not necessarily a part of the scene’s agenda. I felt an urge to make these things more clear.” The show was layered with meaning and surprisingly funny—a highlight of my week at the Fringe.

Space permits me from describing everything I saw, as I attended four or five shows each day for eight days straight, a feat that left my mind spinning and my body exhausted.

But I can offer some advice: Don’t schedule your shows back to back. Leave at least 30 minutes—better yet, a full hour—between each show. Venues are located all over the city, some miles apart, and it takes time to travel among them. Bus stops are located near most of the venues, but buses are frequently delayed due to traffic. Walking is often the best option, but be sure to factor in extra time to get lost in Edinburgh’s beautiful but labyrinthine streets; leave even more time if you’re walking along the Royal Mile, the city’s main throughway and the Fringe’s ground zero. That street is never not thrumming with crowds and street acts.

A packed schedule also means little time to grab a bite. Many of the larger venues, like Summerhall, feature lawns brimming with food and drink vendors, but they draw long lines and you won’t always have time to stand in them. So keep some snacks and a bottle of water on your person at all times. They’re easy enough to find—local groceries like Salisbury’s and Tesco are located all over the city and sell ready-made items for less than a pound a piece. If you eat regularly and stay hydrated, you’ll have much more fun.

Fun, after all, is the Fringe’s greatest takeaway. American playwright Brian Parks agrees. This was his fifth Fringe, and this year Enterprise, his absurdist play about the fate of American businessmen in the wake of a collapsing corporation, won a Fringe First award. When asked to sum up his experience, he said, “Mostly it’s just a lot of fun. Stressful fun, but fun nonetheless.”

And though many of the issues around and at this year’s festival may have stemmed from national policies over which the festival’s organizers have no control, the Fringe continues to provide a space—a very large, carnival-esque space—for artists to create work that will shape the future of the field. As Parks put it, “There’s certainly nothing else like it.”

Amy Brady is a writer and critic living in New York City. Her writing has appeared in The Village Voice, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Awl, Dallas Morning News, and other places.