To find out more about the practice and implications of documentary theatre, I gathered some of the field’s veterans for a frank conversation about their craft, how it’s changed—and how it’s changed them. I found, of course, that they were aware of each other’s work. How could they not be? With the Civilians, Steve Cosson directed and helped create This Beautiful City and The Great Immensity; Leigh Fondakowski served as head writer on Tectonic Theater Project’s The Laramie Project, and most recently unveiled Spill at New York City’s Ensemble Studio Thea-tre; KJ Sanchez, who with American Records created such shows as ReEntry and X’s and O’s (A Football Love Story), is working on a commission from the Guthrie Theater about recent immigrants to the Twin Cities; and Ping Chong continues his ongoing Undesirable Elements, which began in 1992, with a project with teens facilitated by NYC’s New Victory Theater.

Amelia Parenteau: What drew each of you to this form?

Steve Cosson: My introduction came in graduate school in San Diego, where I was a student of Les Waters. Les had been a member of Joint Stock in London in the ’70s and ’80s. We picked a subject and everybody found somebody to interview. It’s been described as a Truman Capote/In Cold Blood style, where you talk to someone and listen to everything they say and write it down as best as you can. We certainly didn’t talk about it as documentary theatre; it was a way of working and generating material. I got hooked on the challenge of it. It spoke to my intrinsic nosiness. I loved that there was an excuse to walk into a stranger’s home and be a listener for them. I discovered that people will tell a lot to a stranger. And my first group of interviews were extraordinary. My subject was very rich people, and they completely blew any preconceived ideas out of the water. I realized the world is a more complicated place where the possibility for discovery is endless.

KJ Sanchez: I was making this work before I realized there was a name for it. In 1992, when I was graduating from UC San Diego, my thesis solo show was about my hometown, Tome, New Mexico. It was founded by my ancestors in 1680 and nobody had ever left. As I was growing up, there was a feud over the rights to this land that everyone had communally shared since 1680. Everyone started suing everybody, children sued parents, brothers sued brothers, my grandfather died not speaking to his brother for 13 years, even though they lived right next door to each other. Knives were pulled in bars, a gun was pulled in church. So my very first foray, before I knew what this was, was a solo piece scratching the surface of where I came from.

Then as a member of Anne Bogart’s SITI Company for the first few years of the company’s life, I learned the process of editing, because we made shows based on found copy. I later learned from Steve and from my fellow early Civilians about being a non-judgmental listener. If you don’t let them know how you feel, then they will say anything. I went back and finished that play I started for my thesis, Highway 47, on an NEA/TCG career development program for directors. After seeing the show, one of my mom’s first cousins from the other side of the town called her up and said that by seeing these stories onstage, she saw they were all pretty much in the same boat. That’s when I loved this form and haven’t looked back.

Ping Chong: I’ve been making work for more than 45 years, and it changed around 1990. I was invited to make a show about van Gogh in Holland for the centennial of his death. This was around the time of the American/Japanese trade wars. I asked my producer if I could frame the van Gogh project within the history of Japan and the West. As opposed to my previously allegorical work, this was the first work in a decade-long quartet about Asia and the West. I call them “poetic documentary,” since they use documentary sources as the primary text.

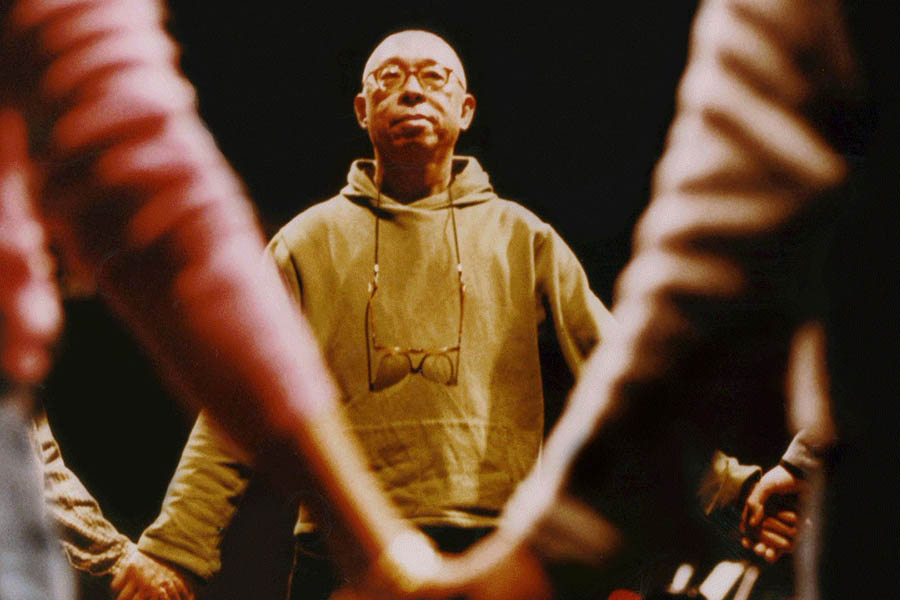

In 1992, I made my first piece in the Undesirable Elements series, and I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t go to school to learn how to interview; I learned on the job. For that first one, I didn’t know where I was going with the material. Now, it’s been 25 years of the Undesirable Elements series, and I’ve seen how it’s a tremendous privilege to create a space in which other people can feel empowered to speak. At the beginning, there was more of my imposition of myself on it, since I didn’t know what I was doing yet. I became more hands-off. It’s all about being able to give voice to these people and to create bridges, since the people onstage and in the audience are one community, but the conversation isn’t always there.

Leigh Fondakowski: My story starts with Anna Deavere Smith, seeing her perform, then coming to understand that she was trying to find characters and patterns of how people present themselves. I was so taken by that and with her as a performer that I set off on my little journey to make my first piece, I Think I Like Girls, with a bunch of queer women from different generations. Then in 1998 Matthew Shepard was killed, and when Moisés Kaufman gathered the Tectonic Theater company together to propose a play, he said, “Do we as a theatre have a play which is in the national dialogue around this event?” Because it was the first time that a homophobic hate crime had received national attention. That question reoriented whether we as theatre artists had a responsibility. That was when I began to formulate this process as a playwriting technique. You’re exposed to things you don’t see in your daily life as an artist in New York, which shifts your perspective in an interesting way. I want to make a play that people care about. I’m interested in what else the form can do.

Sanchez: Can I take a moment to ask you guys how you cope with different kinds of sadness that we traffic in? I make a deal with myself, like, I say: Okay, after this show, I’ll go have a nervous breakdown. I find a way to keep myself in check, because it’s not about me, it’s about whatever the show is trying to reflect.

Cosson: When I teach on the subject of making theatre this way, I always go back to the idea that no matter how you make plays, they’re going to work the way all plays work; there are basic dramaturgical principles. We categorize things into various niches, and if you write a play that is drawn from interviews, then sometimes that’s not even considered playwriting.

Sanchez: We are playwrights, even if we are using transcripts from interviews.

Cosson: It’s still got to work as a play. When it comes to sadness or suffering, I ask myself if that suffering is connected to some kind of forward momentum as part of a larger story.

Fondakowski: There isn’t just the artistic burden to make plays, but a theatrical event that is also compelling and interesting.

Sanchez: We’re writers in how we ask questions, and in how we contextualize and frame it. You have to be able to provide an avenue for a new conversation about the issue. What do you have to offer that can’t be done in any other medium, or hasn’t been done already by a great journalist?

Cosson: One thing I think we do differently is we put the audience in the reality in an important and meaningful way. A documentary film can be deeply impactful, but I think a play can be impactful in a different way. We know what we’re seeing in front of us is a fiction, but because it’s happening we experience it as real, and that does make us empathize differently, since we have had those experiences. That’s why it can be something that pivots your life in a different direction.

Do any of you have an interview that stands out in your memory as, “Oh, this is it. This is where I hit my stride and figured it out”? Or conversely where you felt, “There is no common ground here.”

Chong: I got better through doing it. In my first interview, people were all in a room together, that original cast, and I began by jotting down notes with people there. It took me a while to realize that sometimes people had very traumatic experiences, and I had to be sensitive. There’s a need for respect when asking people to access very personal material, to help them move forward gently. Sometimes I have to be ruthless, to push as far as I could before pulling back, though, because it isn’t useful if you don’t get the story.

Sanchez: I can’t be a good listener if I’m judging whether it’s going to go into the play or not. You know if you’re having an interview and the person is assuming what’s going to go on the stage, and they’re basically pitching you their story, then that’s probably not going to have any traction in the long run. But you need to be there to listen, because they’ve given you their time.

Fondakowski: When somebody agrees to do an interview, I believe that there is a reason they agreed to do it. Whether or not they are going to share depends, because I think they’re going to wait and see in the situation if they trust me enough to say it. Usually what I ask now at the end of the two hours is, “Is there anything I didn’t ask you which was important to ask?” Sometimes the heart of the matter comes up when you think the thing is over, someone tells you the story that kind of blows your mind.

Sanchez: My students ask me, “How do you know what goes in the play and what doesn’t?” It’s always personal. Whatever I found surprising or I haven’t heard before, if it changes the way I think about the subject. But you constantly live in this place of, I have a lot of good material, I have a lot of interesting research and I don’t know if I have a play yet. That’s when the harmonies and dissonances between the people you are listening to become incredible. It reminds you to truly live in the moment.

Fondakowski: When we were working on Jonestown, it took us three years to get interviews because people were very hesitant. We were about a year into our process when somebody in our team made a document that said with big capital letters, “WHAT NEEDS TO BE TOLD?” That’s not the right question. The question is what is the story you want to tell. With a story like Jonestown, I felt incredible responsibility.

Cosson: Would it be interesting to talk about the appetite for difficult subject matter that is often connected to a documentary-like play? I can say there’s a marked difference in the U.S. versus the U.K. The U.K. seems to be much more on board with “get us something difficult.” And America generally wants to have a good time or a good weep, but often doesn’t want to go in for a good struggle.

Sanchez: Emily Ackerman wrote ReEntry with me, and we were getting a lot of productions, but every theatre was struggling to get an audience—marketing with all the right intentions, but it was a struggle. One presenter in particular, we had about 11 people in the house, and it broke my heart. I guess the real question is, how can we cultivate more interest in it? I feel like audiences are going to come and feel bad about it, feel bad that they have to care, feel bad that all these terrible things happen.

Fondakowski: I wish there wasn’t this category. I think when you say the phrase “documentary theatre,” it has a limiting idea. Each of our works is more extensive in terms of theatrical language. I try to say that my plays are plays, based on interviews and based on real events.

Sanchez: For me, it depends on the show. With ReEntry, and this one that I’m currently making for the Guthrie, I’m calling it a documentary play for my own purposes, because it helps me define the rules of engagement. There needs to be some sort of transparency with the audience about where you are taking them.

Cosson: I try to avoid the “documentary” word altogether, and I try to make sure that nobody uses it in marketing or press releases. Several years ago I made up the idea of “investigative” theatre, which has no fixed definition. It’s an idea of theatre that has some kind of outward-looking process that feeds into the creation of the show. But it’s a little broader and people don’t know what it is.

Sanchez: I love the term “investigative theatre,” but there are times when I don’t think I could use it. For example, with these refugees and undocumented immigrants that I’m working with, there’s a lot of nervousness right now about who’s asking them questions. I think if I used the word “investigative,” then they’d be afraid of who I was, whereas the word “documentary” feels safer. The phrase I generally use is “making plays about real things and real people.”

Cosson: For those of us who do it, we have to be out there speaking about the value of what we do and connecting to the public. Content is not necessarily sexy in the American theatre. It’s not the first thing that shows up when I think of producers choosing a play or how they frame the plays. Especially outside of New York, there’s only one or two places which are training everyone how to experience theatre.

Fondakowski: I do think that there are artistic directors out there who are able to recognize new narratives.

Cosson: It’s also the value of independent companies with regards to this work. Because many of these theatres might have interest in supporting a project but don’t necessarily have a special projects team that goes into the work of documentary thea-tre. Like José Rivera’s Another Word for Beauty, where in order to make that show we had to spend a month in a Colombian women’s prison, which was not something the Goodman was going to staff. But I have that expertise, so I could manage it.

Fondakowski: We’re creating these kind of models. Theatre institutions, non-theatre institutions, universities, high schools—we’re taking all of these aspects to fund a process that is incredibly expensive, even if you do it on a shoestring. And so that’s part of what’s happening here as well, inventing new ways of doing theatre.

Chong: Undesirable Elements is not always performed in a traditional theatre setting. We’ve done shows in YMCAs, community centers, Union Seminary and Trinity Church in New York, a beauty parlor. Since the Undesirable Elements subject matter varies greatly, each one seems to have an audience that is interested in that subject.

How do you define success for your work?

Sanchez: First, exactly what Leigh said: A project is successful if it stands on its own as a play. But I also define success if I was able to hang onto my own value system and if I was honest in representing what I saw, emotionally, spiritually, and intentionally. And if someone can say that was a good piece of theatre, as cheesy as it sounds. Hopefully we leave behind a chronicle of our communities right now.

Chong: The nature of an Undesirable Elements project is creating understanding, since participants are learning about each other. Success is when someone hears a story or perspective from within their community that they haven’t heard before, and the audience gets to join in on that conversation. For example, doing a show in Charleston, South Carolina, one woman came out as a lesbian during the show, to her mother, in public, and a conservative guy spoke up in a talkback to say, “I don’t like gay people, but after hearing her story, I have to think about it again.” Many people haven’t had the opportunity to address things publicly that they share in the show. The reward for me is tremendous, and it’s such a privilege.

Fondakowski: We also have this shared experience that we’re not talking about, which is getting the interview material. I assume you guys have a lot of intimate relationships with people across the country. So that’s also, not to be too cheesy, a profound experience as an artist. And you learn all about these things that you would never normally think about. You become this expert.

Cosson: I can tell how much I’ve changed since doing a piece. Even when you’re telling other people’s stories, you’re entering into those stories yourself. And if you’ve gone beyond yourself to consider other people’s experience with empathy and identification as much as possible, then that is a very important accomplishment. That is why I do the work. In the interviewing phase, I always feel like a bigger and better person. I live in the world in a different way.