Broadly conceived, American documentary theatre (also sometimes called docudrama, ethnodrama, verbatim theatre, tribunal theatre[1], theatre of witness, or theatre of fact) is performance typically built by an individual or collective of artists from historical and/or archival materials such as trial transcripts, written or recorded interviews, newspaper reporting, personal or iconic visual images or video footage, government documents, biographies and autobiographies, even academic papers and scientific research.

I locate three significant moments of innovation in the form, content, and purpose of documentary performance over the past 100 years of American theatre history and practice. The first is marked by the work produced under the auspices of the Federal Theater Project (1935-1939), particularly “living newspapers,” a form itself borrowed from agitprop and worker’s theatre in Western Europe and Russia. While the content of these early American documentary plays was drawn from everyday life, particularly the experiences of first- and second-generation working-class immigrants, their form was decidedly modernist, embracing collage, montage, expressionism, and minimalism in a symbiotic relationship with new forms of visual art, early cinema, and atonal musical compositions.

These plays were sometimes built with the input of communities where artist-workers were stationed as part of FTP and the Works Progress Administration. But mostly artists crafted and performed them as an educative or cultural service, using techniques that may or may not have resonated with audiences who reflected the stories or characters depicted. This tension between ethnographic content and modern or postmodern artistic form remains a hallmark of documentary performance, whether defined by features or practices.

If we mark the start of American documentary performance history in the early 1930s, it is easy to see the centrality of social and political crises to its content focus and aesthetic properties. On this timeline, the second key moment of development happens in the late 1960s, when the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, global economic upheaval, and the newly dominant televisual mass media invited or compelled a new generation of theatre collectives to explore, employ, and explode the formal and aesthetic properties of documentary. Companies such as the Living Theatre, the Open Theatre, Bread and Puppet Theatre, Teatro Campesino, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe questioned dominant media and state narratives around economic and social oppression, democracy, equality, and the rule of law.

These subjects were not wholly new to theatremakers. In the 19th century, artists in the emerging genres of naturalism and realism were also social reformers and took inspiration in both content and form from the lived experience and social/political struggles of “ordinary” people, their personal histories, and their environments. But in the 1960s and ’70s, as traditional definitions of home, family, nation, and creation were contested with new fervor, energy shifted away from conventionally structured and produced plays and theatre spaces toward unbounded and unscripted events (“happenings”) as well as highly controlled multimedia installations and durational work that tested artists’ and audience’s physical capacities. At the same time the impulse to craft a theatrical world from real lives, experiences, and places evolved into a rawer, distinctly autobiographical, artist-driven type of storytelling.

This turn to artist as source material marks the third historical development in American documentary theatre, particularly in the work of Anna Deavere Smith. In Smith’s work the primacy of written, archival documents takes a backseat to artist-collected, interview-based materials. Smith also functions as performer, presenting painstakingly studied and faithfully rendered bodies and voices (across race, ethnicity, and gender) using her own body as tabula rasa, activating new questions about truth and authenticity.

Other artists of this late 1980s, early 1990s era, including Tim Miller, Holly Hughes, Spalding Gray, Karen Finley, and the collective Pomo Afro Homos, tell more singularly personal stories of identity formation, the struggle against oppressive religious ideologies, discriminatory social hierarchies, and inequitable political systems. The dramaturgy of these monologue documentaries frequently echoes the collage organization and expressionistic elements of the 1930s living newspapers, eschewing a realistic approach to time and place. Instead the performer’s emotional reality shapes the storyline and the audience’s experience of social history as it meets an individual’s lived life.

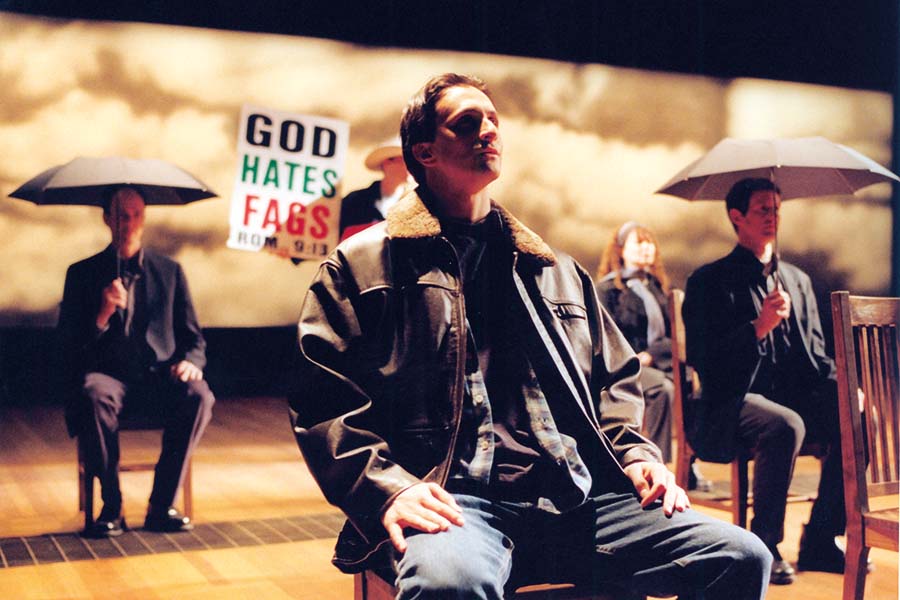

Perhaps the most notable script of this third era is The Laramie Project (2000), a three-act play that takes the murder of college student Matthew Shepard as its catalyst event. We see the history of the play’s construction in its opening moments, as company members describe how they traveled with director/writer Moises Kaufman from New York City to Laramie, Wyo., where they conducted interviews with community members in the wake of an anti-gay hate crime that brought international attention to this relatively small, isolated Western U.S. town. Using Kaufman’s “moment work” technique, Tectonic’s interviews became the centerpiece of their script.

Kaufman had developed “moment work” for an earlier verbatim theatre piece, Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, which stages the three trials that eventually brought about Wilde’s conviction charge of indecency (downgraded from sodomy). While the play, informed by an investment in exposing homophobia in legal and social domains, forwards the notion that Wilde’s prosecution was a miscarriage of justice, it also dramatizes how Wilde’s own arrogance, racial and class privilege, and appetites contributed to his fall from public grace and celebrity. The play even hosts an out-of-time onstage debate over the artist’s and historian’s roles to combat, reveal, or ignore social injustices.

While Kaufman’s authorship is singular in Gross Indecency, he places the acting ensemble, whom he calls “narrators,” as the central negotiators of the play’s complex ideas about sexuality, aesthetics, and authority. But in The Laramie Project, the actors became co-authors who work as performers and interlocutors, and the play’s central dramaturgical structure is the three-fold act of witnessing, remembering, and testifying. Such meta-theatricality—revealing the mechanics of theatre’s process of collection, creation, and performance—is not a new or singular feature of documentary plays. With the success and influence of The Laramie Project, however, it has become a central aesthetic conceit of work built from interviews, especially if those interviews are conducted by the same artists who then construct and perform the documentary script.[2]

And yet, as Carol Martin, a professor at NYU, has noted in multiple books and essays on what she terms “the theatre of the real,” American documentary theatre gains more public attention for the subjects it presents than for its aesthetic innovation or critical complexity. While many artists working in this domain hope to call into question shared understanding of terms such as “real” and “fact,” for Martin and other critics and historians, such interrogations exist to varying degrees based on the extent to which documentary theatremakers connect their performance’s politics to its aesthetics. In her 2014 book Dramaturgy of the Real on the World Stage, Martin argues artists working in the “theatre of the real,” often outside the U.S., engage a broad and self-conscious examination of how theatre “participates in the larger cultural obsession with capturing the ‘real’ for consumption, even as what we understand as real is continually revised and reinvented.” Martin leaves us with key questions about when and how, even if we, as artists or audience members, can “definitively determine where reality leaves off and representation begins.”

In the contemporary moment, when the blur between the real and the represented is daily, systemic, and overarching, companies such as the Civilians, which bills its work as “investigatory theatre,” deliberately avoid the label “documentary,” arguing their theatre asks more questions than it answers, does not press any particular political agenda or audience action, and embraces theatrical devices such as music and dance to expose dimensions of absurdity, hyperbole, and non-linearity—essential tools to understand the complex social, political, and cultural forces that shape our daily life. This new moment in documentary theatre’s development is one marked by a mix of urgency, intensity, and hybridity. The Civilians, for example, deliver their content across multiple media platforms, including but not limited to theatre and concerts, including via podcasts.

The latter illuminates an aural dimension of communication that documentary theatre more broadly is exploring (or returning to). In the past five years, audio-based story platforms and site-specific events (such as narrated walking tours, podcast and smartphone plays, even car plays), have expanded the everyday dimensions of the theatre “stage” and its performance and reception.

Against this backdrop we can see why debates over whether the category of “documentary” is a formal genre or a set of practices and politics have churned among filmmakers for decades. The rise and proliferation of reality TV, devised theatre, and now podcasting or serialized audio storytelling has intensified this discussion across fields and industries. Offered as an antidote to staid scripted dramas where narrative control is in the hand of a writer or writing team, reality TV has been marketed as unfiltered and unadulterated, uncovering the rush of emotion available within the risky and uncontrolled flow of everyday life.

Since the early 2000s, devised theatre, which encompasses practices that have had many names in eras before, has been touted as bringing (or returning) democracy to the rehearsal room, decentering written text in the theatremaking process and allowing artists of all backgrounds and skills to become authors of a performance script, upending narrative conventions to tell the story of any idea, individual, or event. This kind of performance can be built by an artists’ collective, but it is also accessible to non-artist communities, thereby shifting the aesthetic authority to those with lived experience over artistic training.

A two-fold insistence on questioning and shaping reality gives documentary theatre its unique character, whether one prioritizes its content or form. First, by dramatizing lesser-known or counter-narrative aspects of contested or supposedly stable experiences, documentary theatre unsettles what we thought we knew in an effort to upend privilege, invert the margin and the center, and interrogate structures of authority. Second, theatre offers a unique opportunity for a body-to-body experience in a shared material space, which makes it a complicated and dangerous art no matter its form.

While theatre can only ever be a facsimile of the real, to create worlds and inhabit them is a powerful act of imagination and resistance. Consequently, documentary artists bear particular public scrutiny and critique because of their influence over the selection, shape, and reception of their work. The paradoxes of documentary theatre as both real and representational, multivocal yet clear, direct, and coherent, critical of a unified truth yet believable and compelling, are part of its complex, innovative, and ever-evolving history.

Jules Odendahl-James is a dramaturg and director, and serves as director of engagement in the humanities department at Duke University.

[1] In the United Kingdom and Australia and in nations who bear a legacy of colonialism (e.g., India, South Africa, Palestine, Lebanon) or totalitarian oppression (Turkey, Poland, Argentina, Slovakia, among others), “verbatim theatre” or “tribunal theatre” shares some of the formal, rhetorical, and political features as the American documentary theatre history I will sketch here, but with its own, unique national and aesthetic dimensions. For those interested in these traditions, I recommend Martin’s Dramaturgy of the Real on the World Stage; Get Real: Documentary Theatre Past and Present (edited by Alison Forsyth and Chris Megson); Verbatim: Techniques in Contemporary Documentary Theatre (edited by Will Hammon and Dan Steward); Playing For Real: Actors on Playing Real People (edited by Tom Cantrell and Mary Luckhurst), and Cantrell’s Acting in Documentary Theatre. [2] Perhaps not since Emily Mann’s Execution of Justice (1985), about the assassination of gay rights activist and board of supervisors member Harvey Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Muscone by former board member Dan White, has there been an American documentary play of such direct, political, and rhetorical influence as The Laramie Project. Not only did it have an off-Broadway run, but since its publication in 2000, it has had more than 400 regional, college, and high school theater productions. In 2008, many of the original company members and Kaufman returned to Laramie and crafted The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later, including interviews with both men who were convicted of Shepard’s murder. All of this public attention kept Shepard’s story alive, as well as drew attnention to the drive for hate crimes legislation that specifically addressed crimes against LGBTQ citizens. In 2009 Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed into law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.