When Sam Shepard died on July 30, we asked his ex-wife O-Lan Jones to write a memorial; you can read her finely rendered remembrance here. There was more to say about the passing of this American icon, though. Below are tributes from four of his colleagues and collaborators.

Downtown Hero

Sam Shepard. For me he was always the icon, the beacon, the guiding light of contemporary writers. Along with giants like Ms. Kennedy, Mr. Wilson, and Ms. Shange, Mr. Shepard was one of the greats I wanted to emulate. And yep, he was a white guy—yep. But more importantly, for me at least, Sam Shepard was a writer who could trace and track the epic mythic raw American thrum that runs underneath and vibrates throughout so much of this country. I would read his plays and his novels and short stories and see the films he wrote and think, “I want to write like that.”

He got how folks are connected and disconnected, and he was intense. And I could relate to that. Maybe cause we both had dads who were in the Army. Maybe cause we both moved around a lot growing up. Deep South, far West, rusted country, life so real that it hurt. He was downtown. He was close to the bone. No, he didn’t write about my specific experience, but in writing about his own, he showed me how to write about my own. Reading his work and seeing his work helped me grow as a writer. And once, a conversation we had helped me keep writing.

It was back in 2009. Me and Jo Bonney were doing an early workshop of Father Comes Home From the Wars. We were at the Public, in the Shiva. It was such an embryo of a show that, as those of you who saw it will remember, I was part of the cast; I was the Musician, sitting onstage, playing my guitar for underscoring and singing the songs. It was a beautiful workshop and the audiences were encouraging. One night as we took our bows, the lights went up in the house, and, sitting next to Tony Kushner (!) and John Guare (!)—there was Sam Shepard(!!) Oh! Goodness! The house was so small that you could make easy eye contact with the audience. I caught his eye and we shared a smile.

About a year later, I was having one of those difficult days. We’ve all had them. The days when nothing seems right, your friends seem snarky, your writing sucks, and you want to quit the business. You’re on a train that’s tracking a downward spiral. (Champagne troubles to be sure, but real enough.) I was walking home, late in the evening, my head hanging low.

I heard a guy’s voice: “Hey!”

I didn’t answer, of course. I don’t answer when guys hey on the street.

“I liked your play!” the voice said.

This was not a voice inside my head.

I turned to look at the speaker.

Sam Shepard, sitting on a stoop of a building, smiling at me.

“I really liked your play,” he said again.

Mr. Shepard lived in my neighborhood, a mix of ritzy condos and NYU professors’ digs.

“Mr. Shepard!” I exclaimed. I might have shrieked. I was in a state of amazement.

“Sam,” he said correcting me.

“Sam Shepard!” I exclaimed.

He had risen off the stoop. Came forward. Shook my hand.

“Your play was great,” he said again. “And I really liked the songs too.”

I know I had some kind of response—a mumbled, garbled “thanks” as my thoughts choked in my throat. Here was one of the greats of theatre and art and everything complimenting me. I shrank, I grew…I was in that instant resurrected by the kindness of a man who—

(CRACK! I am writing this right now and there is a thunderstorm outside and the lightning just struck a tree right outside my window. CRACK! And I leap out of my chair, then sit back down and keep writing.)

I was resurrected in that moment by Sam’s kindness.

“Wanna walk?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said.

And so we walked. East. For about an hour. Walking and talking. Talking about writing. And about growing up and moving around a lot. And about our dads in the service. And about songwriting. He said he had the darndest time writing songs and wondered how I went about it. We stopped at Veselka on 2nd Avenue. I offered to buy him a drink but he said he wasn’t doing that. So we had coffee. And he treated. And then we walked back to our neighborhood. And shook hands and hugged. The hug that writers hug. I told him he was a hero of mine. “That’s all right,” he said.

Thank you, Sam Shepard. For being so brave and brilliant. For lighting the way for writers like me. For giving me another strong set of footsteps to follow in. And thank you for being kind to me. May I do the same for others.

Suzan-Lori Parks, playwright

A Gift in the Room

I first met Sam Shepard over a pool table a couple blocks away from the Eureka Theatre in San Francisco. It was 1975. He had left London, stopped in Nova Scotia (where he wrote Action), and arrived out West. He came to see his wife, O-Lan Jones, in Pinter’s The Birthday Party, which I directed. Word of his arrival as a resident playwright at the Magic Theatre spread through the Bay Area like a fire. People began carrying around his plays, reading Tooth of Crime out loud, and marveling at this new force in our midst.

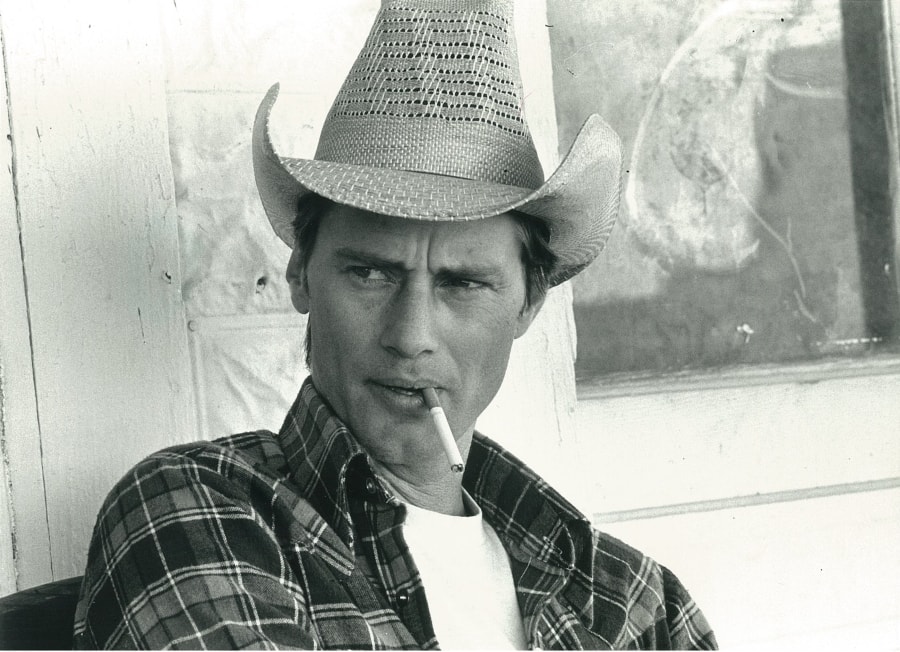

Sam quickly gathered up a coterie of actors to perform his work, including Jones, James Dean, Fred Ward, Ebbe Roe Smith, and John Nesci. They had the swagger of a gang. The poster for the Angel City premiere is burned into my brain: All of them, including Sam in shades, just too tough by half, giving a kind of “fuck you” stare into the camera. The Magic was on top a bar called the Rose and Thistle Pub, and sometimes drunk, exuberant patrons would walk in the into the 49-seat theatre during a performance. But the work killed. The gang was tied into what he was doing and the text soared. His presence galvanized the entire community.

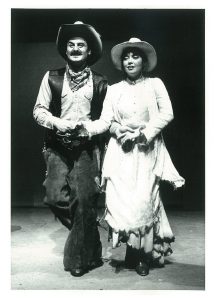

In 1977, I asked Sam if he had any plays in the drawer that we could premiere as part of the inaugural Bay Area Playwrights Festival. He pulled out The Sad Lament of Pecos Bill on the Eve of Killing His Wife, an operetta just a tad shorter than its title which he created with composer Katherine Stone. It had a stage direction about the heroine I’ll never forget: “She’s dead but sings anyway.” Sam never saw it, because he was shooting Days of Heaven.

That production led to five more collaborations in about as many years. Each play was a gift. Each one was an amazing landscape of images to harness. With extraordinary words to put in the air. To land on an audience. To evoke in a room. To reveal what is elemental in us.

Making the show often had as many close calls, lucky breaks, and turns of fate as the plays themselves I got to direct the American premiere of Curse of the Starving Class, because Sam recommended me to Joe Papp, the founder and artistic director of the Public Theater, on the strength of what he had heard second hand about Pecos Bill. I got Papp’s call in the church basement that was the Eureka Theatre and high-tailed it to New York. The production went well, but Sam couldn’t make it. He didn’t fly in those days, and New York was outside of Mill Valley California truck range.

In 1978, we did Suicide in B Flat at the Magic, and we were finally in the room together. I remember turning a scene on its head several times trying to crack it. After he watched the scene, Sam asked, “Yeah, but what’s the situation?” The actors and I had missed something and he put us back on track. The score for the production was improvised and the piece became a great wedding of sound and text with a live band each night. Sometimes Sam would sit in on the drums just offstage and his presence goosed the entire event. Some performances felt like a train wreck, while others landed like a great, connected jazz set.

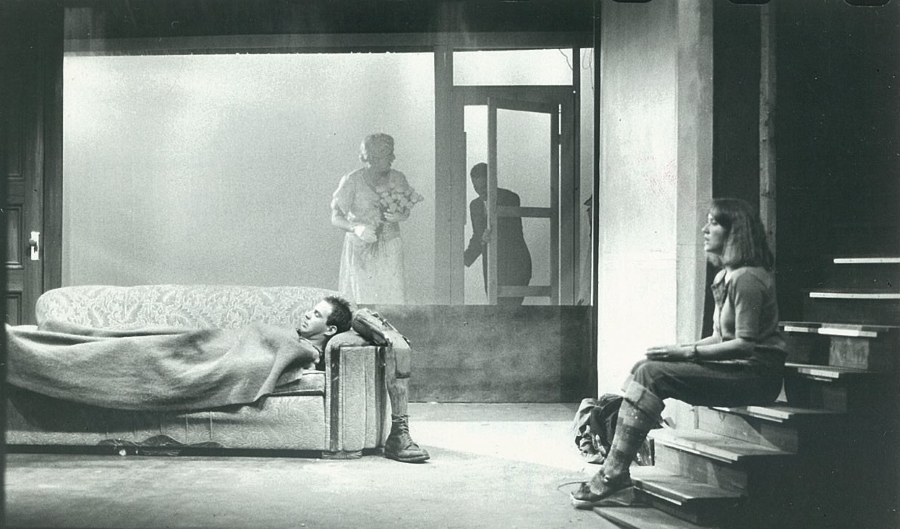

Sam loved actors. He knew that only through their genius would his words take flight. And he wasn’t in a hurry. Things grew as they grew. The actor had to learn the notes and then play the notes and then riff on the notes, and he gave them some amazing notes to play. Rehearsals for Buried Child were a blast. It was a wide open room. Sam and I would watch the actors work, then we would respond, and then they would dialogue with us about the work. The first scene in Act 3 between Dodge and Shelley had the actors and I banging our heads against the wall, and then Sam said, “It’s a scene about an old man and a young girl.” With that simple note, he opened up an inexhaustible landscape to mine. We made the New York production while Sam stayed on the ranch out West. The Pulitzer followed.

While in rehearsals for True West at the Magic the following year with Jim Haynie and Peter Coyote, Sam suggested we all go to see the Leonard vs. Duran fight on closed circuit. It had all the dynamics of the play: Leonard as the intellectual writer Austin and Duran as the outlaw Lee. They both had their own weapons bloodying each other primally and brutally.

When Sam and Joe Chaikin were creating Tongues at the Magic they needed an eye in the house, because Sam was performing percussion live seated behind Joe, so I got to give them some feedback. These two men had been connected for almost two decades from the early 1960s at Caffé Cino. Their deep love and respect for each other was evident at every moment. In their co-creation they harnessed what is sacred about the theatre. Its mystery. Its poetry.

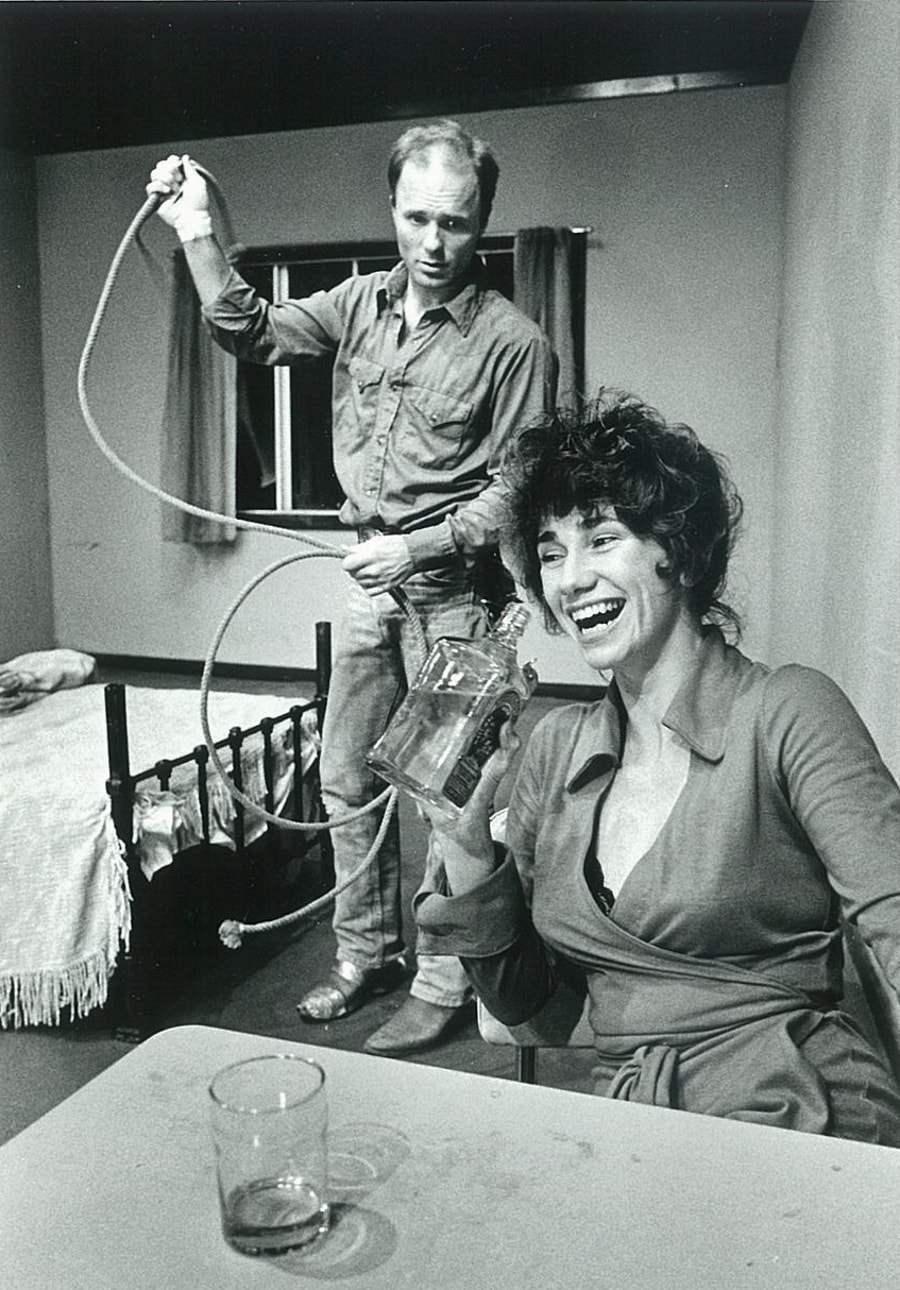

I enjoyed watching Sam direct the premiere of Fool for Love with Ed Harris and Kathy Baker at the Magic. We were sitting in an empty back row when Ed was making a bad, terribly menacing pun that Sam wrote about a date and a fig. He shot me a smile that said, “Yeah, I wrote that. Ha!”

Our last encounter was in Los Angeles. I was directing A Lie of the Mind at the Mark Taper Forum. When Sam was directing the play’s premiere in New York, I had urged him to cut some scenes. In my production, I put them back in. I was on a motorcycle going out to see him play polo in Palm Springs. The bike broke down on the San Bernadino Freeway. I never got there.

I found out 20 years later that he felt that I had violated our deal by adding the scenes back in. I never knew him to be precious that way about the work. I always felt such freedom. But I had violated some pact, some oath in his terms. The bike breaking down on the freeway going to the desert always seemed like an excellent ending, One he might have written himself.

Robert Woodruff, director and teacher

The Natural

In the early ’60s we, artists of different kinds, in our 20s, mostly middle class, each arrived in Greenwich Village, NYC, as if drawn by a magnet. Likely we were lured by an idea of freedom, each fleeing the prison of our emotional origins.

In the early ’60s we, artists of different kinds, in our 20s, mostly middle class, each arrived in Greenwich Village, NYC, as if drawn by a magnet. Likely we were lured by an idea of freedom, each fleeing the prison of our emotional origins.

Our generation was raised in a world of lies. Preachers lied to us, politicians, and Mad Men advertisers. Our parents lied too, outright, or by denial. We were raised in a 1950s Rock Hudson, Doris Day picture-perfect postwar world of growing prosperity. But underneath that opaque saccharine facade we sensed dysfunction, hypocrisy, and trauma from the war—on familial and national levels. Sam Shepard’s father was an alcoholic and possibly abusive, as we may surmise from Sam’s play Buried Child.

We young artists arriving in Greenwich Village viscerally sensed there must be a more truthful and joyful way to live. Profoundly skeptical of respectable conventional social values, and with a dawning political awareness, we felt a lust for life.

Our powerful erotic urges were closely linked with our creativity.

Many of us Greenwich Village playwrights were gay. Sam was flamboyantly, abundantly straight. His ebullient sexuality was charismatic—you could see it sparkling in his eyes, and it later helped make him a movie star. Ellen Stewart, La MaMa herself, the living, beating heart of Off-Off-Broadway, once remarked that Sam was like “juicy Lucy,” as Ellen called the erotic urge, flowing plentifully and creatively. Dylan Thomas, a poet much in vogue then, once dubbed Eros “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”

We were ambitious too, hoping to “make it.” But Broadway, producing then mainly psychological realism, wasn’t interested in rebellious, anti-commercial new theatrical experiments. So instead of living in the rectangular blocks of uptown, our home remained bohemian Greenwich Village, with its baroque twists, turns, and streets with names like Christopher, Cornelia, and Bleecker. Somehow there we became a community.

On 14th Street we marveled at the Living Theater combining art and radical politics, applauded and performed in each other’s plays in the newly minted Caffe Cino, La MaMa ETC, and the Judson Church.

I first read Sam’s name in the fall of 1964 in Michael Smith’s rave Village Voice review of Sam’s Cowboys and The Rock Garden at St. Marks Church-in-the-Bowery: “Sam Shepard has written a pair of provocative and genuinely original plays, feeling his way, with an intuitive approach to language and dramatic structure, and moving between ritual and naturalism. His voice is distinctly American and his own.” A star was born.

I first read Sam’s name in the fall of 1964 in Michael Smith’s rave Village Voice review of Sam’s Cowboys and The Rock Garden at St. Marks Church-in-the-Bowery: “Sam Shepard has written a pair of provocative and genuinely original plays, feeling his way, with an intuitive approach to language and dramatic structure, and moving between ritual and naturalism. His voice is distinctly American and his own.” A star was born.

I met Sam when his then girlfriend, Joyce Aaron, an Open Theater actor, brought him to the Open Theater loft on West 24th Street. Sam was impressed by our collaborative work, and especially by the Open Theater’s brilliant director, my partner in crime, Joe Chaikin. Later Sam and Joe worked together on several plays. But Sam never joined the Open Theater. When I asked him why, he replied, “I just like to work alone.”

An actor too, Sam seemed to invent an offstage persona for himself: Cowboy or Lone Ranger. It worked for him.

As a playwright, Sam was a “natural,” in touch with his unconscious, not standing in its way, letting it express itself on the page. Schopenhauer defined genius as “the ability to discard entirely our own personality for a time in order to remain pure knowing subject, the clear eye of the world.” Often it seems Sam did just that.

Words pouring easily from him, I imagine Sam arranging them rhythmically, playfully, on the page like music. His plays have their own harmony, unlike that of a conventional realistic work.

It’s significant that Sam was also a musician. As a teenager, he and his siblings formed a family band. Sam first arrived in the Village from California with his college roommate Charles Mingus Jr., also a musician. An early job-job for Sam was being a waiter at the nightclub the Village Gate. Later, on the Lower East Side, Sam drummed for the Holy Modal Rounders, an experimental folk band. He seemed really happy doing it.

In the early days at least, Sam rarely rewrote or edited his words. He didn’t censor himself or force his plays to conform to any idea of what a play should be.

I don’t want to romanticize Sam. He had deep psychological wounds. We all do. Accessing in depth our painful spots, our wounds, is crucial to the creative process. In unflinchingly and viscerally touching our pain, letting it spit forth on the page in all its precision and quirkiness, we can create plays in unique, dream-like forms and remarkable contemporary rhythms which may resonate with many.

Sam’s plays bring audiences to see and hear the world differently, more truthfully perhaps.

Thank you, old friend. I will miss you.

Jean-Claude van Itallie, playwright, performer, and teacher

The Last Five Years

Sam Shepard changed the face of theatre. Forever. Through his mind-bending and heartbreaking plays and prose, he bared his soul and swagger while traversing our primordial pasts. For five decades and change Sam has been in pursuit of the mythic bones buried out back, of the visceral energy and emotional tension that makes us human.

His restless, rhythmic dialogue made actors kill to speak his words aloud—-to explore the space Sam left around the words. Helmed by Shepard himself, or as often Robert Woodruff, the early iconic performances of Gammon, Harris, Baker, Coyote, Sinise, and Malkovich cemented our hope that maybe, just maybe, we too could be a part of making something as primal and true.

Sam was Magic Theatre’s most beloved son (founder John Lion had the vision to offer him a decade-long artistic home in 1975), and it is here, at the end of the West, hanging off the San Francisco Bay, that Sam wrote and premiered seven of his seminal works including Buried Child, True West, and Fool for Love. His singular brand of muscularity was forever baked into the walls at Magic, demanding a ferocious, visceral primacy –which ignited a new-play fever throughout the Bay and beyond, and is surely what lured me here, from New York.

His timeless impact is indelible in every new script that lands on my desk to this day; his blood is coursing through generations of playwriting, from Octavio Solis to Lucy Thurber to Taylor Mac.

We forged a friendship over what would be, unthinkably, the last five years of his life. Slumped in Magic’s audience, legs dangling over the theatre seats in front of us, he argued vehemently with me over the ending of a play I was directing (not his); he remained eternally leery of pat endings. He attempted to explain the craft of hunting geese versus deer, and encouraged me to read one of his favorite novels (I tried unsuccessfully—the book, not the hunting).

Years later, over tea one afternoon in the East Village, he joyously recited Beckett and with misty eyes shared the humility he felt in making what would become Tongues with his dear friend Joe Chaikin.

Sam refused to play wise sage; he remained beautifully broken from his first plays in ’64 to his last book of fiction, published in 2017, combing the open road for visages of his lost father, the bygone West of his youth, and America’s forgotten promises.

I last saw Sam in Healdsburg, in Sonoma County, just before he would head home to Kentucky in March. A copy of his newly published work, A Particle of Dread, was waiting for me. Over cups of coffee, Sam and his astounding sisters Sandy and Roxanne shared with my partner and I photos of his cherished ranch, the horses he missed dearly, and the astounding beauty of that land. He confided that he was working on yet another work of fiction and pondered the origin of the Beatles’ “Blackbird.” He dictated a dedication in honor of Magic’s 50th anniversary for Ed Harris to read. Sam asked Roxanne to read the entire piece several times, and with each pass Sam listened intently, making small, careful revisions.

In spite of everything, he was profoundly himself. Searching, like the rest of us.

Making sure that as the words hit the air, they were right.

Loretta Greco, artistic director, Magic Theatre