“After consultation with my Generals and military experts, please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow… Transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military.”

After the Tweeter-in-Chief made that incendiary (and legally murky) pronouncement, protests erupted around the country, and a new musical in Chicago this fall from Permoveo Productions (in association with Pride Films and Plays) has found even more contemporary relevance than its makers might have imagined.

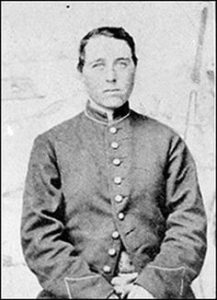

The CiviliTy of Albert Cashier, written by Jay Paul Deratany, with a score by Joe Stevens and Keaton Wooden (who also directs), and which runs Aug. 31-Oct. 15 at Stage 773, draws on the real story of Albert D.J. Cashier, who was born Jennie Hodgers on Christmas Day, 1843, in Clogherhead, Ireland. But it was as Albert Cashier that he made his mark as a brave soldier in the 95th Illinois Infantry during the Civil War, participating in the siege of Vicksburg (where he escaped Confederate capture) and more than 40 other battles, despite being the shortest member of the company.

There’s a history of women fighting wars disguised as men, whether out of patriotism, a desire to join husbands or lovers at the front, a need for wages, or simply a thirst for adventure. The Civil War Trust says that “conservative estimates of female soldiers in the Civil War puts the number somewhere between 400 and 750.”

What distinguishes Cashier is that he maintained that male identity for 50 years after the war ended. He eventually settled in tiny Saunemin, Ill., where he lived alone in a one-room house and worked odd jobs as a laborer. It wasn’t until the end of his life that his biological status was discovered: Stricken with dementia, Cashier ended up in a state-run institution, where he was forced to wear skirts until his death. (There are in fact stories that those skirts—which by some accounts he pinned up to mimic trousers—led to the fall, broken hip, and subsequent infection that finally killed him in 1915.)

A headline in a contemporary newspaper article right after Cashier was “outed” reads “Find Old Soldier Is Just a Woman.” Still, Cashier was buried in his uniform, with full military honors, and with the name he had adopted on his tombstone. (A second tombstone adding the name “Jennie Hodgers” was erected in the 1970s.)

It’s a story that resonates on many levels, and one that Deratany was naturally drawn to. A lawyer and human rights activist as well as a playwright, Deratany’s previous play, 2010’s Haram Iran, about the murder of an allegedly gay teen boy in Iran, was nominated for a GLAAD Award. Deratany found Cashier’s story while looking for real-life inspiration for a follow-up play.

“I’m a history fan, and I happened to run into this story and I thought, ‘My God, this story has never been told in our history books,’” Deratany says. “That historical interest grew sharper, he said, “when I realized that Albert never changed back to being a woman.”

But he didn’t conceptualize it as a musical until Wooden—an Emmy-nominated director, writer, and producer and longtime friend and collaborator of Deratany’s—read the script. Wooden suggested both the musical concept and Stevens, a trans composer who often works in a folk vein, as a collaborator.

Says Wooden, “It was a combination of finding a musician whose style was so perfect for this period, but it’s also essential to bring onto the head of the creative team someone who has that experience. I talked to Joe about this show two years ago. He had already heard about Albert and a lot of his own music deals with his own journey as a trans man, so it was inherently powerful to see him dig even deeper into this character.”

In fact, the song “Bullet in a Gun” was written when Stevens was 22, long before the musical entered his life, and adapted for the show. It’s sung by Dani Shay, a veteran of “America’s Got Talent” and “The Glee Project,” as an anthem of defiance and anticipation.

“We’re pinning this character, who is fighting to define himself, around this historic event of an entire country trying to define itself,” says Wooden.

Shay, who identifies as nonbinary trans, hadn’t heard of Albert Cashier before “Glee Project” mentor Robert Ulrich brought them on board. Pointing to the Wikipedia page on Cashier, Shay says, “I find it interesting that some people still choose to identify Albert as ‘her’ and ‘she.’ We don’t know if Albert was alive today how this person would identify—female-to-male trans, nonbinary—but it’s pretty clear Albert was not identifying as Jennie, and was not going by ‘she’ or ‘her.’”

Shay also notes that the musical invents a relationship between Albert and one of his comrades-in-arms, Jeffrey (played by Billy Rude), captured in a bluegrass-inflected song, “Excuse Me, Sir,” where Jeffrey searches for his pal after Vicksburg.

“His buddy develops feelings for him and is confused by him,” Shays says. Albert’s dilemma, as Shay undertands it, is: “I could choose to live my life with this person, who wants to live by the standards of men and women of the time, and that might be easier. But would I be living life on the terms I want to live by?”

Albert’s circumstances as an uneducated immigrant and a biological woman also presented difficulties, says Deratany.

“I do think it’s much more than a trans story,” he says. “I try not to make conclusions. Is this a woman who wanted to fight in the Civil War and live as a man because it was harder to live as a single woman back then? He may have been a gay woman. One of the books I read said that he had a very special female friend, but nothing was obvious in the history that I read.”

Ultimately, whatever Albert called himself or how he identified, Wooden finds his story moving on many levels. “We’re not dealing with a story that is the topic of the week or just timely,” he says. “We are dealing with a human being who should be judged by their actions and how they lived their life, not by any particular label.”

Wooden is also insistent that there’s a degree of hope in Cashier’s story.

“There are far too many stories about disenfranchised persons that are just sad,” says Wooden. “A big thing for us is that not every story that has a sad ending is sad. Albert lived for 50 years exactly as he wanted to. And that is a stunning, beautiful, just admirable moment that we as people and American citizens should celebrate.”