They say all press is good press. But for Steven Cosson, artistic director of documentary theatre troupe the Civilians, the reality is a bit more complicated. On May 23, The Washington Post ran a piece with the headline: “In Trump budget briefing, ‘climate change musical’ is cited as tax waste. Wait, what?”

The musical in question was The Great Immensity, created by the Civilians, which was a recipient of a $697,177 grant from the National Science Foundation. The NSF’s budget in 2017 is $7.4 billion; under President Trump’s 2018 budget proposal, the number would be cut to $6.7 billion.

In justifying the cuts, the director of Office of Management and Budget, Mick Mulvaney said the Obama administration spent too much on “crazy stuff,” giving The Great Immensity as an example. “The National Science Foundation last year used your taxpayer money to fund a climate change musical. Do you think that’s a waste of your money?” he asked rhetorically during a press briefing last month.

Cosson doesn’t think so (and notes that in fact the grant was given in 2010, not 2016).

“I think it’s the executive branch’s attempt to really just silence and censor climate science, and that’s feeding an attack on science more broadly,” he explained last week in a phone interview. “And I think the fact that we were an arts grant actually made it an easy scapegoat for them to go after the science funding.” He also notes that the NSF doesn’t just fund research; it also funds museum exhibitions, films, and live performances geared toward presenting scientific research to the general public in an accessible way.

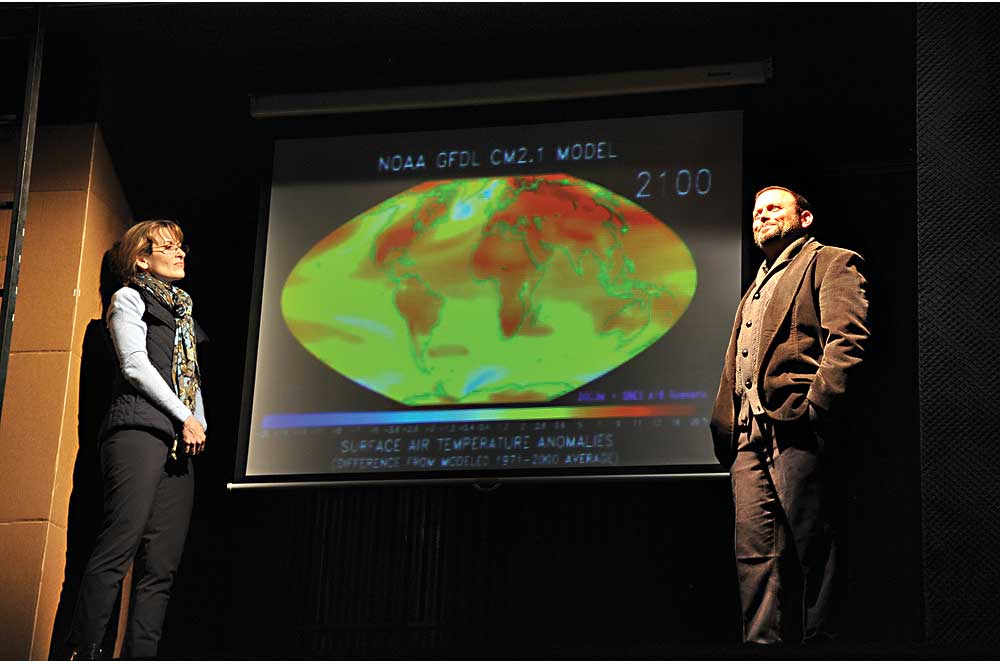

This isn’t the first time Great Immensity has come under fire from conservative politicians. The musical, which ran at Kansas City Repertory in 2013 and at the Public Theater in 2014, follows a woman named Phyllis, who, while searching for her missing husband, uncovers a plot to disrupt a climate summit in Paris. The Civilians used their NSF funding to conduct interviews at the Panama Canal and in Arctic Canada, and collaborated with scientists at the Princeton Environmental Institute.

The musical became a target after its highly publicized New York run. In 2014 House Representative Lamar Smith, R-Texas, told Fox News, “I support basic research, which can lead to discoveries that change our world, expand our horizons and save lives. But NSF has funded too many questionable research grants. Spending taxpayer dollars to fund a climate change musical called The Great Immensity sounds more like a waste of taxpayer dollars—money that could have funded higher-priority research.” Or just be cut: Trump’s budget proposals include massive cuts not only to climate science research but to environmental protections, medical research, and disease prevention (the Environmental Protection Agency faces a $2.5 billion cut and the Center for Disease Control a $1.2 billion cut, among others).

The new administration’s position on climate change is newly newsworthy, of course, because last week President Trump announce that he’ll withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Climate Accord, a pledge by 195 nations around the world to reduce carbon emissions. The move was greeted with near-unanimous scorn and condemnation from world and business leaders, not to mention scientists.

For that reason, among others, Cosson—who previously refrained from responding to criticisms of The Great Immensity—explains why plays about climate change are more important than ever. He spoke to me from New Orleans, where he’s researching a sequel.

Why do you think conservative politicians use The Great Immensity as a talking point?

I think it makes for a convenient sound bite, certainly. I mean, it’s a very familiar tactic: Whenever a particular party in government wants a particular kind of budget cut, cite something which is going to seem like a waste of money to the public. Our NSF grant has been used many, many times over the past several years. But I think it combines two things that many people on the right are not in support of: climate science, climate change research and education, and public arts funding. We of course merged the two, and that presents a perfect opportunity to them. The size of the grant sounds like a lot of money, and when it’s presented to the public or the average voters as, “This is how the government is spending your money,” I assume they think many people will hear that and then will support a great big cut to the National Science Foundation budget and the National Endowment for the Arts.

I think what is telling about this moment is that there’s so much Republican energy behind cutting the science budget, and the attempts by the Trump administration to censor public agencies’ presentation of facts, of scientific information about climate change. In their attempts to eliminate the climate research budget of NASA, they took down climate change information from the EPA website. Ultimately there’s one big agenda, I think, behind the executive branch’s attempt to really just silence and censor climate science, and that’s feeding an attack on science more broadly. That fact that we were an arts grant actually made it an easy scapegoat for them to go after the science funding. It’s a bit of a bait and switch.

When did you realize Great Immensity was a political target?

I can probably go back to when we were awarded the grant. Lamar Smith—he picks a number of projects across the whole federal government that he can showcase as part of the Republican effort to cut spending. I would think not many of the things that he picks are in the Pentagon’s budget. They’re very selective about what areas of the government they determine to be wasteful, and which ones they’re determined are not.

But we did precisely what we set out to do. With the grant that we got, the purpose was to continue the development of the play, to produce it twice—the grant partially funded two productions, the one in Kansas City and the one at the Public Theater. It was very much about public engagement and public education about certain themes and ideas in science through this medium. So [the grant] not only [funded] the plays; all the various education programs we did around it were part of the grant, and also the study and the evaluation of how well that worked.

I don’t think most outsiders—civilians, if you will—understand just how expensive theatre productions can be.

Productions costs a lot of money, and it gets subsidized for the benefit of the public and for the audience, which is great. We complain a lot in this country about high ticket prices, and you can certainly argue that part of that is because our nonprofits and our theatres are not publicly subsidized as in other countries. And it’s something of a vicious cycle: Because it’s not subsidized, the ticket prices are higher, which means only people from certain class backgrounds can buy those tickets, which reinforces theatre as an elitist art form.

So my answer to all of that is: I want a country that has more public support of the arts, where it’s less expensive to go to the theatre and there’s more public access to it. I don’t think that reality is happening in this administration, but I do think that it’s something that those of us in the theatre should not let go as a goal.

What did audiences think of The Great Immensity?

I think we made a particular choice early on that the goal of this show wasn’t to move people who were climate change skeptics or climate change deniers into climate change activists. There are other projects where that’s the purpose. But realistically with theatre projects, that’s not really the bulk of the audience that you’re going to get.

Our hope was to open up a different way of thinking, and part of that was communicating the urgency of the situation and the story, and communicating what scientists know—the reality that many of them have been living in for some time. Another part of it is opening up a way of thinking so people are motivated to actually engage, and to understand that it’s not a lost cause. It is big, but it doesn’t have to be so overwhelming that you disengage, that the urgency can be something to motivate you to action.

Informally in the audience, we heard a lot of success. There were a lot of people who said they saw the show and really felt like they wanted to do something different with their lives. I think it impacted some people really profoundly. We had these detailed reports, and what ideas the audience took, and the emotional experience they had, and how it might impact their actions in the future. It was great to have that kind of data, and it really did show a lot of the very positive work that the show did, and how important it is to combine information with an emotional experience and with story.

I think that’s very much of what was at the heart of doing a theatre project about this subject. It’s not a straight-up informational documentary. Not to discount those, but we were exploring a different way of communicating with audiences. It was informational, but it was also trying to get at the deep stories of how people think and live and make sense of the world and the future and their place in the world—all of that big stuff that theatre can get at. It’s such a big, complex, and urgent subject that I think we should have 500 plays about it every year.

We also did a bit of The Great Immensity as a TED Talk, and Al Gore gave us a little standing ovation.

How can theatre better advocate for climate change?

I think it’s about both fields [science and theatre] creating opportunities for us to interact with each other, and then make work. Make work for the public.