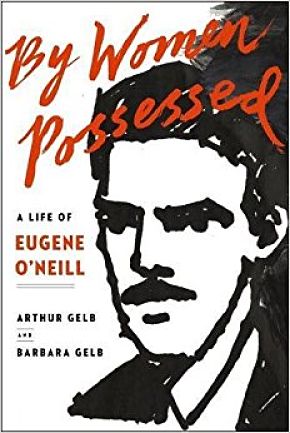

It is virtually unheard of for biographers to revise their work after publication. But Arthur and Barbara Gelb’s seven-decade obsession with Eugene O’Neill recently produced the second of a two-volume rethinking of their earlier O’Neill, 54 years after that landmark study.

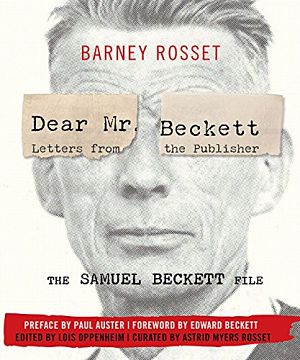

Similarly fervent about postwar playwrights, Barney Rosset’s Grove Press can be credited with bringing the avant-garde into the mainstream, introducing U.S. readers to Genet, Pinter, Ionesco, and Henry Miller, among others. Lacking the capital to compete with the industry’s major players, Rosset created a niche for the banned and the unwanted. His decision to publish Waiting for Godot, and nearly everything else by Samuel Beckett, made Rosset one of the 20th century’s most important publishers during the halcyon days of print. It was he who, in 1953, persuaded Beckett to translate Godot into English for the pittance of $150 and 2 ½ percent of trade copies. Rosset did what most other publishers were reluctant to do: He kept his authors in print. Eventually Godot sold more than 2 million copies. Having purchased the Grove Press label, and its inventory of a few suitcases worth of books, for $3,000, Rosset turned it into a powerhouse.

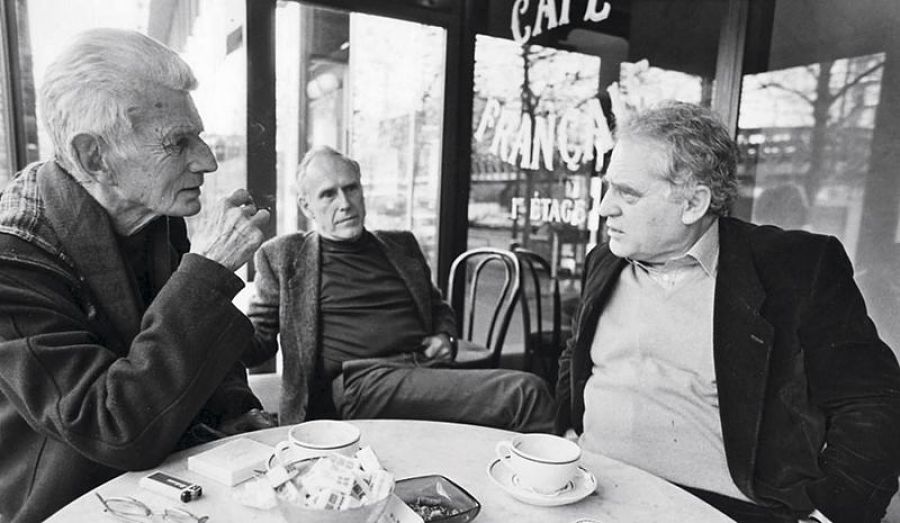

Early in Beckett’s career Rosset was perhaps that writer’s greatest champion as well as an intimate friend, and Dear Mr. Beckett – Letters From the Publisher: The Samuel Beckett File depicts in warm detail the unwavering 36-year bond between the two men. The publisher named a son after the playwright, and a moving photograph at the front of the book, in which Rosset has his arms around his client, reveals a warmth one wouldn’t have associated with the notoriously reclusive Beckett.

But though the cover features a large photograph of the famed playwright, its real subject is the career, proclivities, and relationships of Barney Rosset. The title and its first subtitle, Letters From the Publisher, promise an epistolary volume. Dear Mr. Beckett is much more than that—and occasionally less. Since most of Rosset’s missives were of a factual nature, and most of Beckett’s letters from the 1950s to Rosset are not included (possibly because of rights issues), the correspondence feels one-sided, and some narrative threads taken up in the letters—notably attempts by Alan Schneider and others to produce Godot—are left dangling. It’s also more than a little odd to find not a single letter of comfort or support by Rosset to his playwright in the wake of initially damning reviews; after all, the publisher would claim “Godot was as thoroughly denounced as anything I can ever remember.”

Larded and seasoned with interviews, Beckett’s doodles, his 40-second long play Breath, commentary and interviews from writers and publishers, Sol LeWitt’s drawing for Come and Go; preceded by a preface, a forward, a dramatis personae, and an introduction; and organized by an editor and a curator, Dear Mr. Beckett resembles one of the large-format 1960s books on happenings. It’s a portmanteau chockablock with memorabilia. If there are too many interviews telling the story of how Godot came to Rosset, and some of the interviews have an “inside baseball” quality about the intricacies of publishing, scholars will be thankful for expansive sections on the creation of Beckett’s Film, the genesis of Rockaby, Susan Sontag’s heretical production of Godot in Sarajevo, the tangled clash over the publishing of Beckett’s unproduced Eleutheria, and Rossett’s eventual firing from Grove Press.

Largely because Beckett trusted him unwaveringly, Rosset fell into the theatrical agent business. Beckett believed his stage directions were as sacred as his dialogue, and Rosset was only too happy to be the guardian of production. When, in 1984, the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Mass., produced Joanne Akalaitis’s Endgame, set in a vandalized subway car—a rather obvious and appropriate concept—and including African-American actors, Rosset threatened a cease-and-desist before Robert Brustein, the ART’s artistic director, had to all but concede in a program note that the production did not entirely represent the play. And yet four years later when the Lincoln Center Theater production of Godot in New York City featured Vladimir and Estragon speaking directly to the audience, violating the characters’ isolation, Rosset was hands-off. Had the ART Endgame starred Robin Williams and Steve Martin and been directed by Mike Nichols (as was the LCT Godot), one wonders if a fuss would have been made.

After Beckett’s death, Rosset’s view of heterodox productions came full circle when he applauded Sontag’s Sarajevo Godot, which featured multiple actors in each role and the addition of 30 minutes of playing time.

Celebrated as Beckett’s publisher, Rosset gained international fame for championing work that other publishing houses wouldn’t touch. By far the most compelling material in Dear Mr. Beckett are the interviews and statements that paint a portrait of a publisher steadfastly loyal to his clients and doggedly committed to opening, as he put it, the “Berlin Wall between the public and free expression in literature, film, and drama.” Despite not liking Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which had never been copyrighted, he released the first American unexpurgated version as “a Trojan horse for Grove”—to set the stage for the epic battle over Tropic of Cancer.

As a freshman at Swarthmore he procured a copy of the Henry Miller novel, the beginning of a publishing saga that would lead to multiple arrests and more than 60 court cases. One could make the argument that Rosset footed the bill for an entire industry by opening the door to a more sexually explicit style by the novelists of the ’60s and ’70s.

A professional subversive, Barney Rosset led a passionate and tempestuous life. A free-love advocate with early Communist leanings, he nonetheless married five times. Hedonist, bon vivant, and provocateur, he was born into money but was profligate with funds. One of his authors, Alain Robbe-Grillet, claimed that no matter what city Rosset visited, he knew where to find a show at 3 a.m. “And he knew everyone. All the whores. All the strippers—he was well known in all those places…. And he handed out money…like Americans at one time did. He had his pockets stuffed with bills, always.”

Except when he didn’t. Whether it was a matter of lawsuits or too many pet projects, the piper eventually came calling in the form of Ann Getty and George Wiedenfeld. They bailed out Grove Press in 1985, retaining Rosset as publisher, only to fire him the next year. The painful finale for Grove caught the normally savvy Rosset by surprise. Authors lent their support, including Beckett, who sent him his first unproduced play, Eleutheria, to publish—only to later recant permission and set off a firestorm between Rosset and the heirs to the estate. Eventually, under another label, Rosset finagled his way to publishing the play.

Dear Mr. Beckett succeeds in making the reader want to know a great deal more about Barney Rosset, partly because it refers to explosive incidents in a glancing way. The questionable decision to forgo foot or endnotes leaves the reader rushing to Google to follow up on a women’s strike against Grove Press, a bomb exploded in the offices by an anti-Castro Cuban, and attacks from the Left on Rosset’s failure to give poor black women the proceeds from The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Dear Mr. Beckett is a book that cries out for another book—a full-scale biography of Barney Rosset.

The Gelbs’ O’Neill: Life With Monte Cristo, published in 2000, recounts the playwright’s early career and gives his actor father the starring role. It concludes just before the younger O’Neill’s first Broadway success, Beyond the Horizon. By Women Possessed resumes a bit later, on the opening night of Strange Interlude. This elision allows the Gelbs to frontload the budding affair between O’Neill and the woman who would share the last 25 years of his life, Carlotta Monterey.

Having gained access to a store of new information after the first book, including many of O’Neill’s most personal letters, previously withheld interviews, and most notably Carlotta’s personal diaries, the Gelbs completely change course in the new edition, emphasizing the influence of O’Neill’s mother and three wives as the key to his psyche.

A former drama critic and managing editor of The New York Times, Arthur Gelb (who died before By Women Possessed was completed) and his wife, Barbara, an author and playwright (who died this year) brought a nose for a story and savvy as interviewers to their three-volume project. At the very least the latest book represents remarkably exhaustive research and detective work. The Gelbs interviewed and discovered the diaries of an extensive coterie of O’Neill’s friends and colleagues. From theatre producers to maids, manuscript typists to O’Neill’s dentist, an enormous cast of characters contributes to a rich mosaic of his life.

Their reading of the plays inevitably runs to biographical explication. Relying on recently available early drafts of the plays, they detail O’Neill’s method of rewriting. And in the case of The Iceman Cometh they’re able to identify the real-life models for nearly all of the characters.

Yet, perhaps enamored of their new research, the Gelbs choose to prioritize the luridly personal side of a great artist. The O’Neill they depict is so troubled, so depressed, so debauched, and so self-destructive that the narrative veers from soap to grand opera and back again. It is a Grand Guignol of personal damage that might easily have been subtitled A Long Volume’s Journey Into Darkness.

A histrionic narcissist, O’Neill was prone to epic, jealous rages—and not only when he was drunk. With fear, loathing, and fascination, he looked to others, especially women, for whatever they could offer. When he wasn’t the center of a woman’s attention, he became sullen, angry, and in need of love, lust, or drink. The women in his life existed to facilitate his writing, and when they didn’t, they paid a steep price. He rarely felt at home, dragging Agnes and Carlotta through an absurd succession of houses, hotels, and apartments. As a parent he had little love and much contempt for his offspring; he fussed over pets and enjoyed the company of his chickens more than his children. He became completely estranged from his two sons, one an alcoholic, the other a heroin addict. Both committed suicide. His daughter Oona, whom he banished because of her marriage to Charlie Chaplin at age 19, eventually drank herself to death.

O’Neill never squandered the chance to play the role of victim of a woman’s treachery. His first betrayer, his mother, Ella, was addicted to morphine. After a shotgun marriage and a child he had no interest in helping raise, there came two calamitous unions. In classic inebriated O’Neill style, he told wife No. 2, Agnes, at their first meeting that he couldn’t live without her because she reminded him of a lover who had just left him.

After divorcing Agnes for, among other reasons, her desire for a career and bearing two children he never wanted, he succumbed to the wiles of a mediocre but exotic performer who was his match in vitriolic combat. The savage epitome of their relationship is an episode dramatized by Tony Kushner in his one-act opera, A Blizzard on Marblehead Neck. Depending on whom you believe, Carlotta either pushed O’Neill out a door into the snow where he lay for hours in pain with a broken leg, or he stumbled outside of his own volition, forgotten by his over-medicated wife. “Conflict was the air O’Neill breathed,” write the Gelbs. No wonder he became a playwright.

Carlotta was the great man’s Circe, mother, guardian, and muse. With money from a former lover, she treated him to luxurious excess and helped turn him into a hypocrite when it came to material desires; in the midst of America’s Depression, they lived the high life in a French chateau. After their initial infatuation, he endured Carlotta for her ability to stage manage his life and decorate their many homes. With his health in decline, they separated briefly; then O’Neill allowed her back to become his nursemaid, as she took control of the future of his work. Although the Gelbs go out of their way to portray Carlotta as the more Machiavellian of the two and place much of the blame on her for O’Neill’s alienation from his children, readers may find it difficult to decide who was worse.

As the narrative ricochets from one diary entry to another, through a seemingly unending stream of interviews, dinner engagements, and hairstyle appointments, the reader is left with an incessant conflagration that makes O’Neill’s plays seem tame by comparison. If his work was Strindbergian, his life resembled Dante’s Inferno. Rather than end with the revelation and success of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, the book concludes with the failing health, death, and burial of O’Neill and then Carlotta. Having lived in personally designed homes and mansions, the master playwright dies a pathetic shell of himself in a small hotel suite, just as he was born in one.

As gripping as the tale of two antagonists can be, the sheer volume of monstrous behavior threatens exhaustion and a loss of proportion. As its title implies, By Women Possessed shines its brightest light on O’Neill’s personal trials, sometimes at the expense of his hard-fought artistry and legacy. Clawing the American theatre singlehandedly out of the doldrums of boulevard fare, he was able to transmute a pathologically miserable life—constant health problems, alcoholism, depression and dysfunctional relationships—into lasting art. Plays were the product of his so-called tragic worldview, but they were also his redemption from the cycle of personal torture that he bore and dispensed.

Michael Bloom is a freelance writer and director and the author of Thinking Like a Director.