A girl of maybe 12 or 13 years old pushes through the doors into the theatre and stops in her tracks, looking at the world onstage: fuzzy purple grass, a raked stage covered in painted sand, a lifeguard chair with a ladder so curved it looks like it could topple at any moment. This is where the Star Belly Beachwatcher (Dean Holt) will sit, a Sneetch with the job of keeping the Star Bellies and the Plain Bellies separate. How does he do this? By watching the big, fat, stark red line right down the middle of Sneetch Beach. “Dad—lookit!” the girl effuses, her eyes gone wide. She’s ready to dive headfirst into the world of The Sneetches.

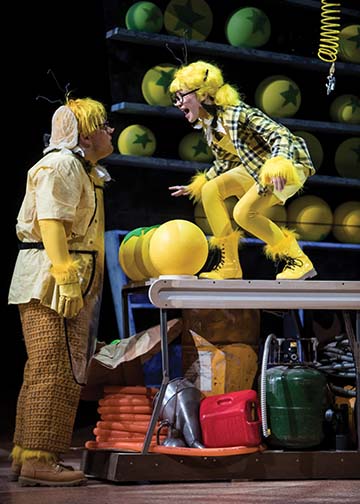

And what a world. As you’d imagine from the mind of Dr. Seuss, the Sneetches live in a colorful world that never met a curved line it didn’t like. The Sneetches themselves are yellow, from the tips of their toes to the tops of their antennae. But some Sneetches have green stars on their bellies, while some have no stars at all.

Seuss wrote The Sneetches less than 10 years after World War II. He’d observed how stars could be used to single out a group of people—as well as the disastrous results. Closer to home, he saw the effects of segregation. On Sneetch Beach, where the original story takes place, stars become desirable, and the Star Bellies use their genetic blessing to oppress those with nothing on their tummies. In the world premiere of Dr. Seuss’s The Sneetches: The Musical, which ran Feb. 7-March 26 at Children’s Theatre Company (CTC) in Minneapolis, the plot was embellished from the original 24-page tale in The Sneetches and Other Stories. Here Plain Bellies labor in a “beach-ket ball” factory, painting green stars on yellow beach balls they will never get to play with. The Star Belly side of Sneetch Beach is perpetually washed in sunshine, while storm clouds hang low over the Plain Belly side. And Star Belly children are taught early on about the way it is, was, and ever will be—namely, the Star Bellies are better than Plain Bellies, and we can’t let them forget it.

But one young Star Belly named Standlee isn’t having it. As played by Natalie Tran—a youngster with a clear voice, boundless energy, and unfakeable sincerity—Standlee is curious about her world, finding delight in the smallest of things. But her question-asking often gets her in trouble and doesn’t earn her any friends. Standlee wanders down Sneetch Beach into the beach-ket ball factory (a toy factory rendered ominous by scenic designer William Boles, with a work whistle to rival Sweeney Todd’s, thanks to sound designer Sten Severson). There she meets Diggitch (Reed Sigmund), an older Plain Belly who recoils at her attempts to play catch, as well as any possibility of their touching. (Star Bellies and Plain Bellies are not allowed to touch.)

Eventually Diggitch pretends to relent and promises to meet her later to play all the Hide-and-Go-Sneetch she wants. In her joy, she gives him a quick hug. Diggitch stiffens. Standlee stands back, says, “See. Nothing bad happened,” and scampers off. When their friendship is discovered, Diggitch is reviled by the Star Bellies and banished by the Plain Bellies. Standlee isn’t sure what she should do: Stick up for her new friend, or fall in line with the other Star Bellies? Keep asking questions about the way it is, was, and ever will be? Or pipe down and accept it?

“What Ted Geisel—Dr. Seuss—is so good at,” said CTC artistic director Peter C. Brosius, “is raising profound ethical issues, profound social issues with such humor, such wit, and such joy. He’s such a radical.” The Sneetches offers those ethical issues in abundance, and the cast and creative team worked hard to bring them to the fore without overwhelming the whimsy. “That’s the balance,” said Brosius, who helmed the production. “The stakes are high, but you’re not making it solemn or earnest. Because [Seuss] isn’t solemn or earnest. He’s brilliant and imaginative.”

So mixed in with those profound ethical questions are some pratfalls, largely by Diggitch (Sigmund), as well as the silly physicality of the Sneetches themselves. Choreographer Michael Matthew Ferrell found contrasting movements for the Sneetches. The Star Bellies are all ramrod posture and Charlie Chaplin turnout, while the Plain Bellies, in their words, “schlumpf,” i.e., bend over so far that their noses almost touch their knees.

But some moments really strike that Seuss-ian balance: In the second act, Mayor Snietzsche (Max Wojtanowicz) gives up his star and finally crosses the line in the sand to the Plain Belly beach. Once over the line, he proclaims with outstretched arms, “I’ve discovered a beach!” It’s a silly moment, but one that also evokes the history of European imperialism, and the one-sidedness of textbooks that ignore the very people living on continents previously “undiscovered.” During previews and on opening night, the line got a big laugh. It worked for grown-ups and young people alike—a goal CTC has for all of its shows, sound designer Severson explained. “If something is purely for kids,” Severson said, “it’s pandering and boring for adults. Shoot too high, and kids are confused. Sneetches works exceptionally well.”

CTC has a long history of commissioning new work for their stages, in part, Brosius explained, because the canon of theatre for young audiences isn’t very large. By expanding that canon, he not only hopes to provide new shows for other theatres around the country but to continually reach young audience members. If all goes well, he said, seeing good work at a young age will give young audiences “a love of this art form for the rest of their lives. It’s both a gorgeous opportunity and responsibility.”

Elissa Adams, CTC’s director of new play development, is often the one offering that opportunity to writers. In the case of The Sneetches, she said, it began with having the rights, then finding the artists to adapt it, but “at least 50 percent of the time, if not more, we actually start with the artists.” From there, CTC and the playwright work together to find and shape a story. To the idea that theatre for young audiences must be restricted to certain topics, Adams said, “There’s no event that doesn’t somehow involve young people or children. Sex, war, politics. Young people are a part of that picture, and are affected by it and live within whatever that story is. Part of our philosophy is there is nothing that is not potentially appropriate for, or compelling to, or of interest to young people.”

Another draw for playwrights: “We commission to produce,” Adams said. CTC’s loyal audience has been built since the theatre’s founding in the 1970s, from a troupe that began performing in 1965, so kids who grew up seeing shows at CTC are now back with their own kids. Those adults may remember CTC’s very first Seuss adaptation, back in 1979: The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins. While Seuss works ranging from The Cat in the Hat to How the Grinch Stole Christmas have become stage staples at other theatres, CTC was the first theatre in the world to develop plays based on Seuss’s books, and they’ve maintained a strong relationship with the Seuss estate since.

When it came to The Sneetches, Adams reached out to playwright/lyricist Philip Dawkins and composer David Mallamud, who’d never worked together before. Adams said their first meeting was a real “blind date.” Added Dawkins, “It’s kind of like an arranged marriage—sometimes it works out.” Dawkins and Mallamud spent about three and a half years collaborating on The Sneetches, writing on their own, conferencing over the phone, or flying in to CTC for table reads and to play demos for CTC leadership.

“I surrounded myself with things that looked, or were, Seuss-ian, then spent several months noodling,” Mallamud said of his process. “If something seemed interesting, I’d record it. Slowly I started to find the musical voice of the piece. I just kept playing until songs emerged. Because the recorder I use has a counter, I know that I generally come up with 800 to 1,200 musical ideas per piece. Most of them are thrown out.”

Mallamud’s big challenge, he said, was finding a unique sonic world for the Sneetches. “I listened to everything I possibly could,” he said. “I really wanted everything to influence this piece, from Bavarian folk to Stravinsky to bubblegum pop—everything.” Those influences are there if you listen, folded into songs with moments reminiscent of the can-can, vaudeville touches by way of Chicago, and Mungo Jerry’s “In the Summertime.”

Faced with the task of creating a two-hour-long show based on a story with only one named character (Sylvester McMonkey McBean, a huckster who instigates the rift between the two groups of Sneetches), Dawkins began his own preparation by rereading the entire Dr. Seuss canon “just to get an overall sense of his work as a full conversation.” He supplemented this reading with Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird to get a better sense of, in his words, “that feeling of being a kid in a world where the adults are making rash and dangerous decisions, but you feel in your gut and in your heart that the adults are wrong.”

It’s no coincidence, then, that young Standlee is a lot like Mockingbird’s Scout: precocious, curious, not afraid to ask why. She knows this makes her an outcast in the Star Belly world; at one point she sings, “I try to shine in darkness, but my light seems to offend.” Dawkins feels strongly that children should be encouraged to ask questions. “When children question authority,” he said, “it’s our job to value what they’re doing, to recognize that they are processing what they’ve been instructed to do. They are forming their own moral grid, they are building the ‘why’ of their ‘what’ and ‘how,’ and that’s good.”

One of the journeys in The Sneetches is Standlee coming to realize this same thing, but she has a low moment where she believes that growing up is all about no longer asking why: why she couldn’t be friends with a Plain Belly, why there’s a red line in the sand separating the Sneetches.

Brosius approached the Seuss estate about adapting The Sneetches for the stage eight years ago, long before the Trump administration was a glimmer in anyone’s eye, let alone its policies. “We had no idea how timely it would be,” Brosius said. Until rehearsals got underway, the script even had Mayor Snietzsche calling for the construction of a wall between the Star and Plain Bellies that both sides would pay for. “Suddenly, the world exploded,” said Brosius, “and that was no longer metaphorical.” The creative team changed the mayor’s campaign to one for widening the line between the two groups.

“It’s not just another production—this show is really important to put on right now,” said Essence Stiggers, a high school senior who played the self-obsessed Mee Mee, older sister to Standlee. The cast is so diverse, she pointed out, that everyone sees this story through different eyes. “We feel it,” added Michael Wieser, who played Mr. Snickety-Sneetcher, the fussy Star Belly schoolteacher. He said green room conversations revolved around political goings-on and how they connect to the work they’re doing. During early rehearsals, the cast looked through a dramaturgy packet—compiled by Adams, who served as the show’s dramaturg—about apartheid, Jim Crow laws, segregation, and Nazi Germany, and some of the history didn’t seem so distant. “The play means something very specific now,” composer David Mallamud said, “but in 10 years it could have a totally different meaning.”

Even the character of Sylvester McMonkey McBean (Bradley Greenwald), a Harold-Hill-meets-Billy-Flynn con artist who promises to give the Sneetches everything they desire (for a small fee) has a fresh if unwelcome resonance. Though Adams said she’s reluctant to compare McBean to the current president (“I’m already tired of that”), McBean’s playing both sides off of each other on Sneetch Beach, and his outrageous, unsupportable claims, inevitably invite comparison. The Sneetches can be read as critiquing not only discrimination and tribalism but also capitalism, and the way perceived status differences and low self-esteem can be exploited to encourage spending, often to reckless ends. As the Sneetches go nuts in a star-on-star-off frenzy, egged on by the rapacious McBean, audiences are reminded that no one escapes implication in a capitalist system.

Heady stuff for a show aimed at children. But Adams really hoped audiences would chew on this on the car ride home. “The idea of buying and selling things,” she said, “and what we buy and sell and choose to buy and sell, is often playing into what we think we want that we don’t have. It’s consumerism.” She added, “What’s cool about Seuss is, unlike Harold Hill, there’s no transformation of [McBean]. It’s not like he realizes what he’s doing is wrong. He’s gonna go on to the next town. That force is always there and will always be there, and it only ever wants to take things from you.”

Balancing McBean’s exhortations to “Spend, spend, spend!” is the socialist organizer Winnifix (Elizabeth Reese). When we first meet her, she’s up on a box with a megaphone, railing against the fumes from the beach-ket ball factory and the Plain Bellies’ low wages. Her flyers are tossed to the ground by morose Plain Bellies resigned to their lives. When Diggitch shows up late to work, she applauds her comrade’s tardiness, thinking it’s an act of resistance. Winnifix is also initially skeptical of McBean’s Star-On Machine (she totes a “Plain Pride!” sign)—that is, until her son Stelvin (the almost elastic Ryan Colbert) asks why they can’t look the same.

Winnifix is one of the few characters who begins the show questioning the status quo and sees her world clearly for what it is: an engineered system of oppression. This is made all too plain in an affecting scene between Winnifix and Stelvin after the Star Bellies discover Standlee and Diggitch’s friendship. When the mayor’s wife and son harrumph at Stelvin, he responds with vulgar gestures and Winnifix intervenes, telling him, “The Other Side will be looking for any reason to retaliate. We must keep our noses even further down. I tell you this not because it’s right but because it’s safe.”

But The Sneetches isn’t all down-in-the-mouth commentary. It wouldn’t be Seuss if it were. Boles’s scenic design, inspired by Seuss but not copying him, keeps the world whimsical and playful even in dark moments; there are snuggle crab puppets. And Dawkins and Mallamud’s charming song “But No” for the Plain Bellies, in which they sing about what they’d do and be if they had stars, is sweet and silly and offers the audience a small breather from the Star Bellies’ oppression. On opening night, Brosius said he was particularly moved by this number, namely by “the commitment, passion, and desperate yearning that the amazing actors who played our five Plain Belly leads showed.”

Another fun addition to the world is Dawkins’s embroidery of Seuss-like language, including “emergensneetches” and “disastrophes.” At one point Standlee asks Diggitch if he apologized because he “flarted.” The kids in the audience liked that one. (Actually, everyone did.)

Alex Jaeger’s costumes were a riot of yellows, with the Star Bellies resembling intensely yellow and very feathery WASPs. Jaeger said Standlee’s outfit was based on something he saw Taylor Swift wearing. The Plain Bellies wore a hodge-podge assortment of clothes: a pinafore here, work boots there, a lot of overalls. Their yellows were plainer and less saturated. Everyone wore black-and-white feathers around their necks that looked vaguely like ruffs. Jaeger’s original designs were closer to what Seuss drew in his book, but the creative team ultimately decided to diverge from it. “Skewing the creatures toward a more human appearance,” Jaeger said, “helps the audience to relate and allows the actor’s physicality, facial expression, and voice to tell the story more clearly.”

In the finale, Standlee and Diggitch instruct the other Sneetches how to make friends and move forward; as the revelry grows and grows, all of the yellows blend and dance like a Sneetch kaleidoscope. Together, they tear up the red line in the sand. The musical may not get to the hard work of rebuilding a society, but it does show the dismantling of oppression, and the importance of literally and figuratively reaching across the line.

Dawkins was struck by the audience reaction to this triumphant moment every night: cheering, clapping, and yelling so loud he could barely hear the music. “When we started writing this play, we knew this was an important message,” he said, “but we didn’t understand how much audiences—fatigued and scared by the state of the world—would really need that catharsis, that moment where two extremely prejudicial groups put aside their differences and agree to put in the work, exercise radical empathy, and literally destroy the barriers between them.” He added, “It’s been incredibly gratifying to sit in the house and be a part of that wave of emotion.”

Theresa J. Beckhusen is a writer and editor based in the Twin Cities.

A version of this piece appears in American Theatre’s April ’17 issue.