Every year I fly to St. Lucia in January to help celebrate Derek’s birthday (Jan. 23). I bring him a sable brush for his watercolors. Traditionally, the island celebrates this day with an entire week of poetry and play readings, a celebration at the Governor-General’s House, ending finally with the “Nobel Speech,” this year given by Jamaica Kincaid.

Many of Derek’s friends come from all over the world to celebrate with him as well, and I am among these hangers-on. We are a staunch if mismatched band of writers from Boston, Spain, China, Italy, England, India, Transylvania, Canada. Derek and his partner Sigrid take us to dinner and honor us with a boat ride down to Soufriere on the west coast of the island. On the boat we sway to reggae music and sip the undrinkable pink punch (the only liquid offered on the boat) until we stop for lunch at the Ladera Resort above the Pitons. Then we turn back up the coast to Castries, stopping for a late afternoon dip in the Caribbean Sea. By sunset, we are sunburned and sated. It is a kind of heaven.

But this year Derek is physically frail, and he cannot make the boat trip down the island. So all of us wander Rodney Bay, cast adrift, more lost than found, sampling the tourist bars, tracing the beaches, and sitting on Derek’s veranda waiting for him to rise from his nap. Caz Phillips and Glyn Maxwell, perhaps his dearest friends now, and I sit with him.

“What one thing do you love about this island?” he demands of me. I reply, “You.” “No, no, aside from me!” (I know there is no right answer to this.) I stutter out, “I love the sound of the sea.” We can hear it from where we are sitting. He is silent, and then…“That is so cliché.”

We cannot separate Derek from St. Lucia, this stunningly beautiful and deeply flawed rain forest of an island, suffering from all the classic Caribbean riches—crime, poverty, corruption—and resting on tourism and volcanic rock. Colonized by the Spanish, French, and British, its language blends an Englishman’s drawl with a French patois. Derek is and will always be St. Lucia to me.

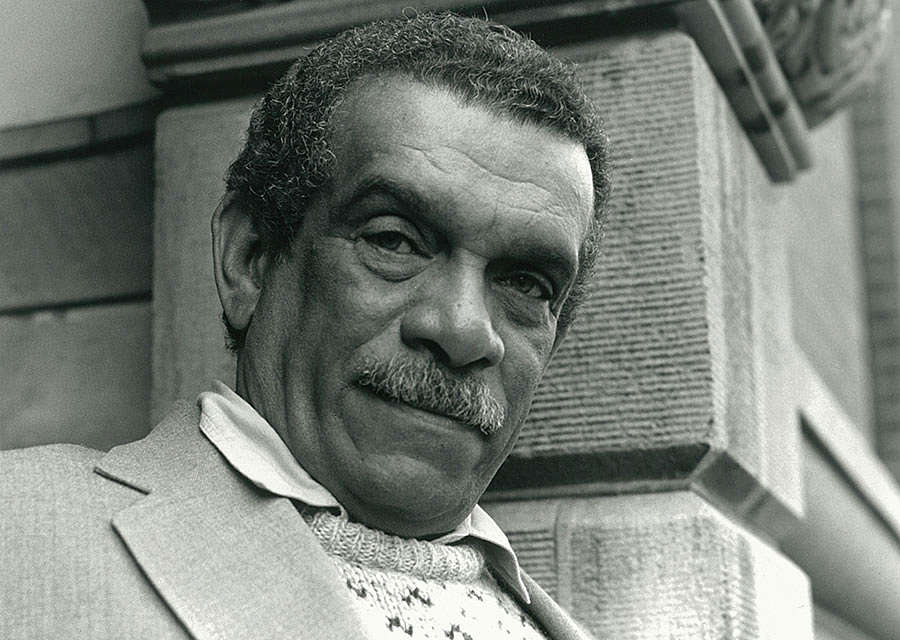

I am not alone in loving Derek, but those of us who loved him did so at our own risk. As complicated as his island, Derek was brilliant and charismatic, an inordinately generous friend, and a prodigious lover of puns. To wit: “A mushroom walks into a bar. ‘Anybody want a date? I’m a real fun guy.’” Aside from this questionable sense of humor (don’t get me wrong—I counted it a good day when I could make Derek laugh), he was also knotty and mercurial. Rooted in what I believe was a true shyness, he was oddly inept in social situations, and he could be boyish and petulant when he didn’t get his way.

Derek played the bongos. He loved cats. He proudly professed himself a “crier” and was easily moved to tears when something touched him, which was often in his later years. Months after the unexpected death of his great friend Seamus Heaney, he would break down at a mention, a memory. It was an endearing quality given his standing in the world of the literati. No sucking it up for Derek. He let everything out. He wore his heart on his sleeve like a talisman.

Many of us who come to celebrate Derek’s birthday were his students at one time or another. We are representative of hundreds—maybe thousands—of writers who Derek mentored over the years, and we have hung onto his mentorship like a guarded jewel: “Yes, I worked with Derek Walcott.”

I was lucky enough to audit his playwriting classes for 20 years at Boston University, where he taught playwriting and poetry in the creative writing department. As a teacher, Derek was demanding, curious, and uncompromising. The inevitable story students pass down is about one unlucky playwright who sat through an entire semester hearing only the first line of his play. But it was no joke: Derek viewed a play as something to be fleshed out and shaped, and he knew that the playwright must know everything about the world she creates. If the beginning of the play doesn’t work, the rest of the play won’t either. That’s a hard lesson for those of us who love the sound of our own voice, but I have held onto this in my own writing and teaching. Derek was always, always right.

Derek’s Boston Playwrights’ Theatre was born from his desire to teach playwriting at Boston University, I suspect because he missed the “family” of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop mightily. Thankfully we were honored to produce a number of Derek’s plays over the years: the mysterious and powerful Dream on Monkey Mountain and the joyous The Joker of Seville, in collaboration with his Trinidad Theatre Workshop. We produced Pantomime, and the cautionary folk-tale Ti-Jean and His Brothers. We premiered Walker, a Play with Music, Derek’s theatrical investigation of the life and death of abolitionist David Walker. And we workshopped his plays over the years: The Odyssey, Ghost Dance, Viva Detroit!

He used the theatre as a workplace, and to him it was a shelter. It has been a gift to me and to my life in the gheatre to learn from Derek, to see his constant revisions, his forced compromises, and his successes. His plays are just like the man himself: huge, full of complexities and humor, musical, and deeply human.

One of my last memories of Derek is him sitting with a young poet on the veranda, with Pidgeon Island some small distance across the sea, talking through the young man’s initial drafts. Derek gave back into the cauldron from which we all came. He demanded focus and forgave youth. He understood that we will all get better if, and only if, we keep writing. His passion never wavered, and he taught by example. I am grateful for it all. I remember the call for excellence, the demand for truth. I miss the bad jokes; I miss his laughter. I miss his mind in the world with us.

I think of an image from his epic poem Omeros: The king going home.

Kate Snodgrass is the artistic director of Boston Playwrights’ Theatre, and a professor of the practice of playwriting in the English department of Boston University.