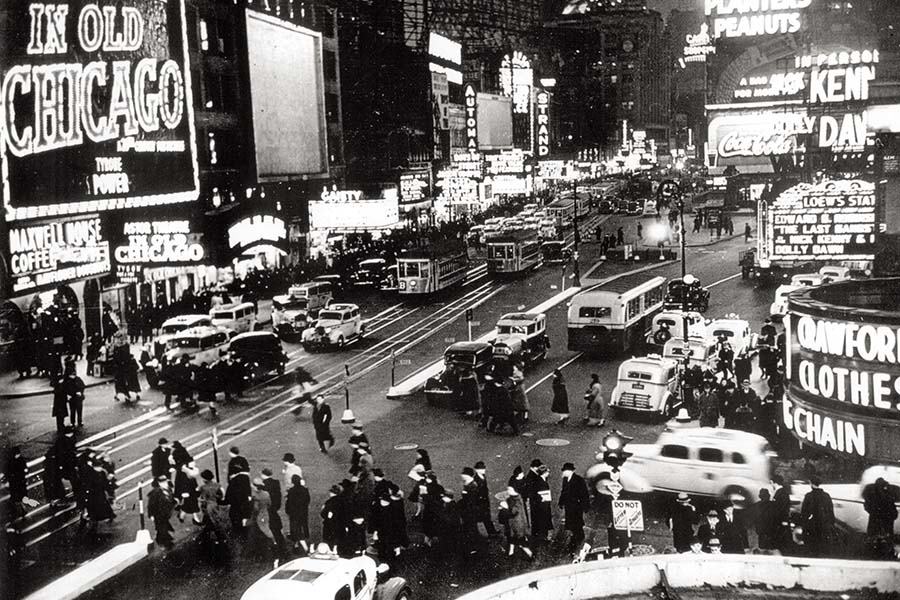

At a recent editorial meeting, the American Theatre staff had a telling exchange: When, one editor wanted to know, would we say was the purported Golden Age of Broadway? He didn’t mean it as a trick question—of course there’s no single factual answer about when any so-called “golden age” begins or ends, let alone whether said era was especially halcyon. He was instead wondering about the claim, in an illuminating article by theatre scholar Garrett Eisler in this issue, that Broadway’s Golden Age ranged from the 1920s to the 1950s. Isn’t there a rough consensus, this editor wondered aloud, that Broadway’s best years ran from the 1940s to the 1960s? Well, yes—if you’re talking about the Broadway musical. But the heyday of New York’s commercial theatre district as a marketplace of new playwriting arguably peaked in the late ’20s—Eisler mentions the 1927-28 season, with its extraordinary 257 openings in 71 theatres—and continued to be the natural home of serious American drama roughly through the early days of network television in the mid-1950s.

The focus of Eisler’s piece is the state of the drama on Broadway in more recent decades. But the conflation of “Broadway” with “musical” is an understandable and common one—the case of a branding campaign succeeding too well. With their splashy musical numbers, the annual Tony Awards, which reify the real-estate gerrymandering that constitutes the parameters of Broadway, have helped give the world the impression that the quintessence of American theatre is song and dance. But without casting too much shade on the great American musical—from a certain vantage point, our culture’s great contribution to the world stage—this issue arrives in part to debunk not only the popular notion that Broadway=musical, but also the common concern that new American plays are singularly endangered by the allegedly debased tastes and punishing economics of our commercial theatre.

As Eisler’s story patiently elucidates, those economics are plenty unforgiving, but hardly more intrinsically so than ever before. In fact, new American plays do make it to Broadway in numbers that have held roughly steady for the last few decades. The biggest change from the “good old days,” Eisler points out, is less in quantity or quality but in provenance and business model: The nonprofit resident theatre movement, which emerged in the last 50 years and has even spread in the last few decades to a handful of Broadway-eligible theatres, has become the primary incubator, developer, and sustainer of new plays and playwrights, both feeding plays to New York and giving them long (and lucrative) lives after their Gotham bows. This state of affairs is neither an unalloyed cause for celebration, nor is it an inevitable or irreversible workaround for an under-subsidized art form; but neither does it offer a simple narrative of decline.

Nonprofits have become big players in the song-and-dance trade too, and in particular with risk-taking, form-breaking musicals, from Hair to Rent to Hamilton to Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812. Another story in this issue tracks the path of three of this season’s new tuners (Amélie, Come From Away, and War Paint) from regional nonprofits to Broadway.

And of course NYC’s commercial district remains host to starry revivals of the American canon, with works by Williams, Wilson, and Miller making routine appearances. This season has again brought us works by each of these giants, as well as one by the less frequently revisited Lillian Hellman, with The Little Foxes at Manhattan Theatre Club. A gimlet-eyed idealist, Hellman had her own ambivalent relationship with the commercial theatre, which she saw as corrupt but inescapable, wrapping her critiques of capitalism in ripe, often pulpy entertainments. In 1962, after her peak as a playwright, she lamented to Thomas Meehan, “I think the day may come when there won’t be a serious Broadway theatre. We’re almost there now.”

Actually, Lillian, not yet.

A version of this piece appears in American Theatre’s April ’17 issue.