David Korins’s career might look very different if he had gotten the part he wanted in his high school musical. He auditioned for Billy Bigelow in his school’s production of Carousel but was cast as Jigger Craigin instead, giving him less rehearsal time and more time to help build the scenery.

“I never wanted to have as tragic an audition experience as that again, but I loved working backstage,” Korins recalls.

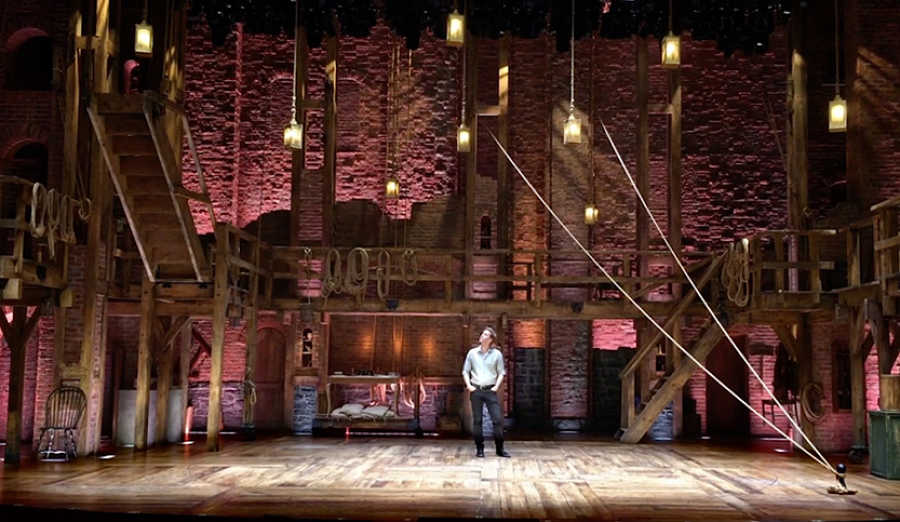

Flash forward several years, and Korins is one of the most in-demand set designers on Broadway, with four musicals this season: Hamilton, Dear Evan Hansen, War Paint, and Bandstand. Not to mention second and third productions of Hamilton, as well as restaurants (Florian and Bond 45), galleries (He was the creative director for Sotheby’s Americana Week, featuring Alexander Hamilton artifacts), TV design (he won an Emmy for designing Grease Live!), as well as working as a designer and creative director to pop stars like Kanye West, Lady Gaga, and Bruno Mars.

“Most people think of me of a theatre set designer because Hamilton is red hot, but my business is only 30-40 percent theatre,” says Korins. “Theatre is how I got into design, and I think that the reason I’ve had success crossing disciplines so much is theatre designers are really great collaborators. We don’t make our work in a bubble. We can’t make our work without collaboration.”

In his green-hued midtown Manhattan office, several associates sit in the open-concept, loft-esque space. Korins, tall, blonde, and boyishly handsome, looks like he might have fared well onstage or screen had that panned out. There is no computer and no drawing board in his corner digs—just a couch and some nice city views. There is a sign that says “Do 30 Pushups,” and when I call attention to this, he says he has a rule that anyone that says it has to do 30 pushups with him. (I pass on the workout on account of no upper arm strength.) He actually used to do 300 pushups and situps a day when he was in tech rehearsal (which as a designer is “all the time” he says). “Maybe the second part of my career I’ll make a techsersize video,” he jokes.

But it doesn’t look like he’ll have any time to create workout tapes any time soon. I sat down with Korins to talk about how he got started in design, what it’s like to have four shows on the Great White Way, and crossing disciplines.

How did you get started as a designer?

I got an internship at Williamstown Theatre Festival (WTF), and I really could see what the path was to be a working professional in the theatre in design. We painted and propped and built scenery, and I spent five years in a row there and then I’ve been back 10 or 11 summers. I’ve spent a lot of time there and met a lot of very important people in my life and collaborators.

I also started a theatre company, Edge Theatre Company, with [director] Carolyn Canter [in 2001]. It was really great. We were able to produce six shows over five years and they were very successful. And it was fantastic to be able to have a calling card that we produce at a very high level in New York City, and they were getting well-reviewed and well-attended. It was a great way to kickstart her directing career and my design career, but it also taught us to be really great producers.

When I was graduating [from University of Massachusetts—Amherst], I applied to Yale [for graduate school] because I thought that’s what you do, and I didn’t get in because they said I couldn’t draw well enough. So I moved to New York and I started assisting on Broadway and I started assisting full-time for other designers and because I was young and because I had skills from all the years at WTF and all the of shows I had done downtown. I basically figured out what the very least amount of money I needed to make monthly would be and every single other penny that I made, I hired people to help me. Because I realized, early on, one plus one equalled five, not two. If you have two people working, you’re more than twice as fast. Here I am almost 20 years later, I basically do the exact same thing still. I carry a huge overheard with my company, but we as 11 people divide and conquer and we work with the strength and power of much more than 11 people. Because I built the company for one reason and one reason only which was to give my collaborators the best possible experience I could deliver as far as creativity and servicing our dreams and imagination. I realized if I spent all my time drafting and building models, I wasn’t going to be nearly present enough in these meetings to be able to really turn around true and great ideas.

Was it hard to first make connections outside of theatre?

It’s always hard branching out. You need someone to be a real visionary in a different field to pick the set designer out and give them, not an architect, a restaurant job. Fortunately the more of those people you bump into, the more chances you get and it becomes easier. I had to jump through a million hoops to get that first feature film. I’m a really fast learner and I had no damn business designing a feature film or Kanye West’s concerts or restaurants, but I was going to make sure they were going to be excellent and beautiful and well-crafted and thoughtful, and when you do those things then you’re going to get hired more.

What is it like having four shows on Broadway at the same time?

The nice thing about those projects is each one of them happened at least once, if not twice, before it got to Broadway. In a way, they are remounting and refining things that we already had a first crack at. It doesn’t mean that the work is easier, but you’re not starting from zero. In Bandstand‘s case, it’s a redesign, but the jawbones of the ideas are still there, it’s just that the eyelashes have changed. With War Paint, it’s basically the exact same set. We’ve added a few things for a rewritten opening number, but it’s essentially the exact same set. The thing that I’m most proud of is they are all frequent collaborators and people I’ve worked with often. I’m really proud of the teams of that I’m part of, and I’m really proud of how varied and different each show is and how well I think each design in particular serves each one of those stories that we’re trying to tell. If someone saw all four shows, it would be really interesting study in here’s one designer’s voice working in four totally different ways and four totally different visually vocabularies. I don’t have a visual agenda. My goal is serve the narrative the best possible way I can even if I have to take a back seat because it’s not about the set.

What is your design process?

I try to start every process with a limitless budget, a limitless timeline, and I think of myself as limitless in regard to what I have to do. And I don’t try to think about the future trajectory, but because I have in my DNA the ability to build and engineer things, I can’t divorce myself from thinking about. I knew that if we were successful in Chicago with War Paint, we would eventually get to a Broadway theatre so I didn’t do something foolish. There’s a whole bunch of long-running shows on Broadway so there’s only five or six potentially available theatres. So I took an amalgamation of all of those five potential theatres, and I made a mashup ground plan and I designed the set to fit inside one of those things because I’m not foolish. At Paper Mill [with Bandstand], we couldn’t do that because the space is too big. That is a literal barn and we had to design it for that space with hopes that if we got lucky enough to get a theatre and momentum to come into town we would shoe horn it into a Broadway theatre.

Bandstand, War Paint, and Hamilton are all period pieces. Do you have a process when you do something from a historical era?

Every single design process, whether it’s a restaurant or a gallery or a rock festival or a piece of theatre, is the exact same to me. It always starts with some sort of a source material and it starts with a client and an idea of what it is that you’re trying to achieve. In the case of Hamilton, it was Lin and Tommy [Kail] and the producers of Hamilton. In the case of a restaurant, it’s a restauranteur, and then you’re trying to figure out what is it that they want to achieve. And secondly, what is it that they want the patrons or their audience to feel when they’re having the experience? And what do they want those patrons and those audience members think about when they leave the experience? My job is to talk to my collaborator and really get a sense of what it is that they want people to feel and think before, during, and after the experience and then use all of the tools that I have at my disposal—whether it is line, texture, color, architecture, scale, proportion, whatever it is—and use all of those things to try and get people to feel that way. But the number one thing is figuring that out and then research. So whether it is Helena Rubinstein’s apartment on Fifth Avenue or it is New York City in 1776 or it is referencing old Arsenio Hall shows, it all starts with research. It used to being going to the picture collection at the New York Public Library. Now it’s a lot about books and Internet. I feel like what you’re doing as you walk around the city and the world is you keep your eyes open and you’re filing things away in your mental rolodex of images to pull from later, and the more you travel, the more you see and the more you’re filing things away to pull from.

You document a lot of your process on Instagram. In the lead up to the Tony Awards last year, you shared a lot of design concepts that didn’t make it to the stage in Hamilton. When and why did you start doing this on social media?

It’s funny, I have documented my work forever. I like to think of myself as someone who has the best possible front row seat because I’m sitting there in rehearsal with Bruno Mars and I’m sitting there in rehearsal with Lin-Manuel Miranda. I love taking pictures; I document everything painstakingly in our office—every design, every drafting, every rendering, every piece of research, every model. So I’ve been doing a version of “page to stage” for 20 years. Instagram is basically someone signing on for an advertisement for you every day. Some people take pictures of their food. Some people take pictures of their kids and their dogs and their cats. Some people take pictures of their work. The thing I’m doing is showing people the process of making art. No one’s ever seen a picture of food that I eat, but they see a picture of process. You could see Hamilton a hundred times and you will never see Lin in his costume writing on his laptop, but you will on my Instagram. I remember as a kid growing up, the only access I had to behind the scenes was Michael Jackson’s making-of video for Thriller, which was amazing to get to see those zombies in between takes. My Instagram is bringing that version to people all over the world.

How did you start working with Kanye West and other pop stars?

Kanye actually wanted to make his album “My Beautiful Darkness of Fantasy” into a stage show. I happened to be in La Jolla doing a show and he lived in L.A. at the time. We had a meeting and he asked me if he could hire me as a creative director to take that album and make it into a stage show. He was also about to start a whole bunch of promo performances on his way to headlining Coachella, so we did South by Southwest and Lollapalooza and a whole bunch of different shows on the way to getting back and then eventually launching what would be his next album. I worked with him as a designer, as a creative designer, at times as a costume consultant, as all sorts of different things. Lady Gaga and Bruno Mars came to me years later through industry connections.

I like doing rock ’n’ roll, because with theatre you really have to serve a much deeper, nuanced story. If there is a moment where George Washington sits down at his desk and is writing Hamilton a letter, we need a quill, we need a letter, we need an inkwell, we need a desk, we need a chair. And you then try and infuse it with some theatricality and some visual storytelling. But if Bruno Mars is singing “24K Magic,” it’s a three-and-a-half-minute-long song in which music has a very quick through line to your heart. He doesn’t need anything but a thing that looks awesome, so the storytelling is much bigger, broader strokes.

So I like doing both. I don’t know that I would ever want to do just one—theatrical design or pop shows or rock shows. I like doing an opera, and then doing a television show, and then doing an installation, and then doing a movie, and then doing a gallery. Because I actually feel like the more you know and the more you’re flexing those different kinds of muscles, the more you bring to things.