So it was Zoot Suit time again on Feb. 12, when a revival of this Luis Valdez play opened officially at the Mark Taper Forum, just one year shy of the 40th anniversary of its birth, when it exploded on that same stage with the force of a sociopolitical A-bomb.

That was then.

Originally commissioned by the late Gordon Davidson, then-artistic director of Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, this 1978 play marked the first time that a powerful Latin American voice—crackling with self-deprecating humor, music, fury, dance, and dry wit—was invited to assert itself in a major mainstream theatre.

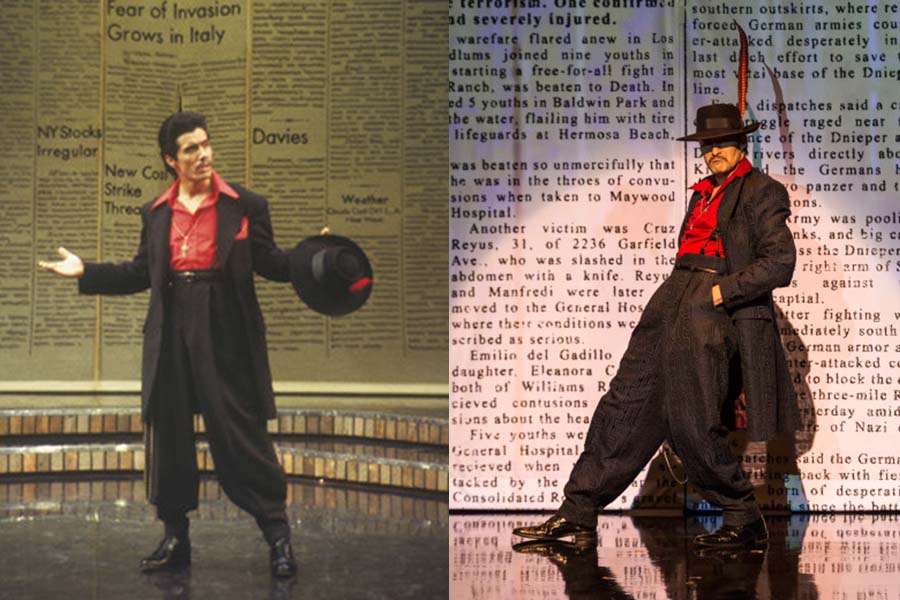

The play Valdez delivered that year was based on a real incident: the 1942 Sleepy Lagoon murder of a Los Angeles man, and the so-called Zoot Suit Riots of 1943, which arose from subsequent racial clashes, resulting in Latinx people being tried, convicted, and ultimately released for inadequate evidence. Valdez fictionalized the events, infusing his play with allegory, song, choreography, and a touch of mysticism. He also created El Pachuco, a larger-than-life symbolic character representing Chicanismo—essentially the Latinx soul.

It was a rousing piece of theatre that marshaled plenty of attention. It also was the first time the Latinx community could see itself on a major stage, in a magnifying mirror that reflected an image they actually recognized. They flocked in massive numbers to see a show that spoke to them in a language—both verbal and existential—they could understand, which delivered a form of respect they yearned for. Let’s call it self-respect. Above all, it gave them visibility of a kind they had not experienced before.

And this is now.

Inadvertently, the world has caught up with Zoot Suit. Because of the wave of anti-immigrant feeling emanating from Washington, D.C.—and elsewhere—these days, the timing of this revival turns out to be propitious. While social attitudes in the last few decades have in many ways loosened and become more accepting in much of the country, bigotry still infects other parts. And the conservative vision of the current administration, invoking a regression to policies that take a narrow nationalistic stance that recall an ugly past, has made Zoot Suit reemerge as—whaddya know?—a fresh protest drama.

It isn’t new, of course. Zoot Suit delivers the very same message it delivered in 1978. But it is tricked up in a throbbing new production by writer/director Valdez that is more physical, thrilling, and vigorous than ever. Christopher Acebo’s sleek modern set makes total use—top to bottom, back to front, and side to side—of the same Taper space where the play sprang to life almost 40 years ago. This production retains the best features of the older one—newspaper stacks standing in as furniture for the ever-present press, for instance—while taking advantage of stagecraft’s technical advances with all its bells and whistles, enhanced by Pablo Santiago’s bouncing lights and David Murakami’s projections.

Above all the production sparkles with Lalo Guerrero’s galvanizing music, mixed with well-chosen standards from the 1940s catalog and some of Daniel Valdez’s enduring compositions (he serves as musical director now as he did then). The play makes the most of the fusion of sassy, sizzling choreography by Maria Torres and of Ann Closs-Farley’s visually dazzling, rainbow-colored costumes, with period wigs by Jessica Mills also there to remind us that these really are the ’40s.

Those are the very strong plusses.

If there are minuses, they are the same that came with the show in 1978. Zoot Suit had a legitimate axe to grind when it made its inaugural appearance. Initially prompted by the spillover from the United Farm Workers grape strike (La Huelga), El Teatro Campesino‘s broadly satirical style gave the original Zoot Suit the edgy stridency that often accompanies political plays. The characters have never been very deeply developed. All those newspapers, loudly proclaiming the increasingly sensational news, don’t allow for the kind of introspection that deep connecting requires.

There’s one exception: Henry Reyna, the story’s protagonist and implicit leader of the 38th Street gang, played here by Matias Ponce. Henry is a man more dragged into this scuffle than eager to find it, unlike his hotheaded younger brother Rudy (Andres Ortiz), who never looks before he leaps. (In a nice touch, Daniel Valdez, who played Henry in the original production, and Rose Portillo, who played his love interest then, now play Henry’s father and mother.) But Henry is the only character we really get to know.

This dearth of greater depth is no fault of the cast, which is consistently strong. This play was agitprop then and it’s agitprop now, and agitprop always renders relationships secondary to the message. What distinguishes this piece from so many other politically charged plays is the overall excitement it manages to generate in the process. In delivering its message it still manages to brim with life, humor, and energy.

Surprisingly, a lot of what I wrote when I reviewed the 1978 production for the Los Angeles Times still applies. Example:

[Zoot Suit] invalidates a strong political reaction to the dramatized event by reminding us that we are in a theatre, “a place of pretense,” and frees us to experience it for its sheer theatricality… [It] implores us not to think but to experience… It’s an important directive because Valdez’s characters… could be accused of being very brown and white—the good guys and the bad guys. Yet [Valdez] has taken what was an energetic but rambling piece… and honed it…”

Those “good guys” and “bad guys” are still “very brown and white,” but the joie de vivre of this revival is undeniably up a decibel or two. When Valdez says he understands the play better each time he directs it, you may take him at his word. He has trimmed some unnecessary fat from the original script, and in the process of modernizing the stagecraft he has invested Zoot Suit with a life force that mitigates its preachiness.

His greatest invention was and is the shadow presence of El Pachuco, a mythical character created out of the ether who serves as a symbol, yes, but also as a bridge between reality and a form of magic realism. Portraying this sly, surreptitious bad hombre propelled Edward James Olmos into a career as a film and TV actor when he played the role in the original staging. Damien Bichir’s performance as El Pachuco in this revival is at least as compelling as Olmos’s, while adding a very sexy dimension to it. He remains the dominant figure, lording it over everything, exhibiting the grace of a dancer, the wiliness of a snake, and the ultimate seduction of a Don Juan down to his deepest Aztec roots.

In 1978 I wrote: “By the time the piece is over, Valdez has achieved exactly what he set out to do: not only given us a story with a traceable plot, but also used it to pull us inside the Chicano, made us understand his pain, his pride, his baloney. We walk out warm and dazed.”

We do. Today’s production continues to be informed by an inextinguishable mix of freshness, nostalgia, acumen, and innocence. It is a story born of a not-so-different time that is good to revisit, especially when its message, though sheathed in so much fun, has regained a lot of its original sharpness.

Zoot Suit was a huge hit in Los Angeles the first time around. It was a unifier. It spoke very directly to its audience, and we know that the best theatre often is the kind that does that. Let’s not kid ourselves: Alienation was one reason it did not win over the critics or the audiences when it moved itself to Broadway in 1979. Broadway couldn’t relate. The show later found receptive audiences in Cuba, Mexico, and South America, where they most definitely could relate.

Will this rebirth transcend its California roots and appeal to other norteamericanos? And does it matter? These are the questions that theatre must pose but never needs to answer. Answers belong to audiences. Because the ultimate reality is that this play, really, is not just about one segment of the population of the world so much as it is about the behavior of the human race. All of us.

As of this writing, the current revival at The Mark Taper runs through April 2. It has been extended. Three times. Are we getting the message?