“Events are considered morally injurious if they ‘transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.’” —U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, quoting a 2009 article in Clinical Psychology Review

In the aftermath of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (our Afghanistan engagement), the issue of veterans’ reintegration and mental health has garnered a remarkable degree of attention. Media scrutiny of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and awareness of programs such as Mission 22—which calls attention to the number of daily veteran suicides—highlight America’s desire, however fitful, to address the needs of its war fighters.

But well-intentioned as many of these pro-veteran efforts are, some emerge from or promote superficial understandings of issues facing veterans, particularly post-traumatic stress (PTS) and moral injury. Similarly, American plays written in the last 15 years have increasingly addressed veteran reintegration, with varied results and nuance. From my own point of view both as a theatre practitioner and a veteran of Operations Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Enduring Freedom (OEF), this trend provides a unique entry point to consider the relationship between America’s theatre and its veterans. I offer this article as the opening salvo in what I hope to be an ongoing and generative exchange.

Over the last decade, as military operations in Iraq shifted from invasion to occupation to surge to drawdown, and finally withdrawal, American theatre witnessed an escalation in plays addressing the wars. Whether examining the effect of war on service members and their families, as Lydia Stryk’s American Tet (2005) and En Garde Arts’s BASETRACK Live (2014) so powerfully do, or exposing civilian audience members to simulated combat scenarios as in Josh Fox and Jason Christopher Hartley’s Surrender (2008), each play makes claims about what it means to be military. Given the widening chasm between the military and civilian populations, theatremakers must carefully examine and refine our representations, particularly in regards to reintegration and post-traumatic stress. This is not an attempt to guide American theatre away from political representations about war and war fighters. I offer this critique as a means of examining the current discourse in American theatre and its impact on veterans.

Grappling with how to represent the emotional stress of war onstage presents unique challenges. The first and most obvious: How does a playwright who has not experienced this specific type of trauma approach an informed understanding? Often playwrights turn to documentary theatre practices such as interviewing to develop stories. Paula Vogel and the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia, for example, held workshops with veterans and actors to craft Don Juan Comes Home From Iraq (2014). Quiara Alegría Hudes, whose Elliot Trilogy I talk about below, relied on close relationships with relatives. Other playwrights over the last decade found inspiration from secondary sources—from headlines and media reports. Finally, there were plays completely conjured from fiction and/or imagination, reflecting the playwright’s political understanding of the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Apart from the aesthetic value of each work, in the aggregate these plays have presented a narrow vision of service members or veterans. Those of us who returned from wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere are not homogeneous in our beliefs, experiences, or methods of processing events in the theatre of war. Yet the overwhelming majority of fictional military characters in the last decade battled a similar form of PTS or moral injury that incapacitated them and/or prevented their transition to society. In Julie Marie Myatt’s Welcome Home Jenny Sutter (2008) and Shawn Fisher’s Streetlight Woodpecker (2016), veteran characters, physically and morally wounded from direct action in combat, turn to alcohol or drugs. In Vogel’s play, Captain Don Juan’s spiral often borders on caricature. Although, to give credit where it’s due, Vogel, like many playwrights and actors involved in plays on this theme, recognized her position as a civilian and acknowledged her limitations in representing veterans’ stories onstage. This kind of humility gives me hope for a fruitful dialogue.

But the “worst-case scenario” characterization oversimplifies a complex situation. First, this discursive frame erases the emotional and physical difficulties facing soldiers who serve in capacities other than infantry (foot soldiers). Not every person who experiences combat is infantry, and being in infantry does not guarantee that a soldier will see combat. This feeds into a class distinction already at play among many veterans: those who were in the infantry and those who were not. What’s more, there are many ways to experience combat. As George Brant’s Grounded (2013) explores, a service member can experience combat without even being physically in the area of operations.

Second, not everyone who witnessed combat has PTS or a moral injury, and of those who do, many are able to transition successfully into the civilian world. In other words, veterans, even those with post-traumatic stress, should not be represented exclusively as loose cannons ready to explode. Please don’t misunderstand me as diminishing the importance of discussing PTS or moral injuries. On the contrary, by contextualizing the stress of war and its personal impact, theatremakers can help unravel dangerous mythologies that persist about veterans returning from war.

While there are many more examples, I’ve illustrated my thesis with a look at the work of three contemporary playwrights, none of them military veterans, and all of whose plays treat the subjects of PTS and moral injury among veterans of our recent wars.

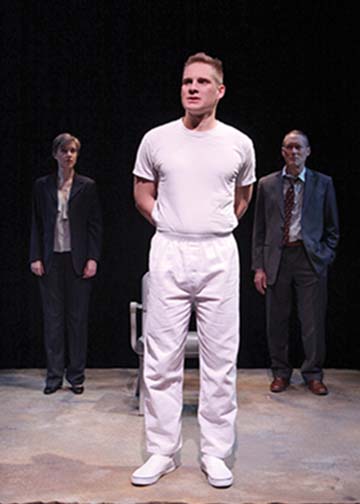

The first is Bill Cain’s 9 Circles, which premiered at Mill Valley, Calif.’s Marin Theatre Company in 2010 and is receiving its New York City debut at the Sheen Center, Feb. 21-March 19. The primary character in this play, Pvt. Daniel Reeves, suffers from an extreme version of PTS and is both physically and mentally prevented from rejoining society. Cain leads us through a descent into Pvt. Reeves’s mind as he acknowledges and accepts the gravity of his murderous actions while deployed to Iraq. Cain took inspiration from the real-life story of Pfc. Steven Dale Green, who received several life sentences for participating in the rape and murder of Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi and her family in 2006.

Drawing on the allegorical structure of Dante’s Divine Comedy, Cain opens the play at a meeting between Reeves and a lieutenant in the infamous Iraqi “Triangle of Death.” Reeves, a 19-year-old soldier from Midland, Texas, has a mental condition for which the Army discharges him honorably. A short time later, Reeves wakes up from a one-night bender to realize that he has been imprisoned and sentenced to death for raping and murdering a 14-year-old Iraqi girl during his deployment. In a series of nine total scenes, Reeves shuffles among lawyers, a priest, and a psychiatrist to reconstitute the full event in his mind.

Cain’s use of the Inferno’s structure allows him to draw parallels between Dante’s journey into hell and Pvt. Reeves’s journey toward death. The closer that Pvt. Reeves gets to his execution, the more he and we learn about his crime. Like Dante, though, as Reeves gets closer to his personal hell, he also begins to long for absolution. At the beginning Reeves is a grunt who “wanted to kill everybody.” By the end, however, he feels remorse and accepts his painful death as penance for the torture he inflicted on the Iraqi girl. True to his Jesuit tradition, Cain finds the redeemable within a monster.

As an indictment against American military negligence, Cain is less concerned with the actions of one tragic figure than in the larger crime of war itself. (In fact, the required reading list for Marines includes Black Hearts, which makes a similar case about accountability.) But while he builds a masterful argument, I question the use of the worst-case scenario to build the anti-war case. Cain borrows his story from an anomalous event and uses it to represent the whole. Like his real counterpart, Reeves is an undereducated young man from a small town who grew up with very little parental care and spent his formative years on the wrong side of the law, and who exhibited signs of mental illness from a young age. In fact, his juvenile criminal record meant that Reeves (and Green) had to enter the military with a moral waiver—a classic case of “go to war or go to jail.” In other words, this is a person who should arguably have never been allowed into the military.

In the discourse of PTS, 9 Circles delivers a profound critique of the military’s responsibility to its warriors while simultaneously reinforcing potentially negative stereotypes of those who deployed to a theatre of war. By defaulting to the worst-case scenario, Cain implies, perhaps unknowingly, that going to war turns service members into violent predators who have an utter disregard for law or human rights. This claim carries serious implications for war fighters trying to reintegrate back into society. Even as some soldiers are valorized once home, civilians typically maintain a watchful eye to see when they’ll lose control. And this has real social impact: Employers often refrain from hiring former military out of fear that they may suffer from PTS. According to a 2012 report by the Society for Human Resource Management, 42 percent of the employers polled consider PTS to be an obstacle in hiring veterans. Personally, I have lost track of the number of times someone asked me if I have PTS just because I was deployed. The narratives that drive this misunderstanding can undermine a veteran’s ability to feel connected with society again.

Quiara Alegría Hudes’s Elliot Trilogy takes a drastically different approach to these themes than 9 Circles. The first of the three plays, Elliot, a Soldier’s Fugue, which had its 2006 world premiere at the Culture Project in New York, tells a generational story of the wartime experiences in one family through three separate wars: Grandpop served in an all-Puerto Rican unit during the Korean War; both Pop and Ginny served during the Vietnam War (he Marine infantry, she a nurse); and Elliot, 19 years old, is a Marine in Iraq at the beginning of OIF. Elliot, who is partly based on Hudes’s cousin Elliot Ruiz, left Iraq with both physical and moral injuries. While on deployment outside of Tikrit, Elliot’s leg was sliced open by concertina wire when a car crashed into the checkpoint he was guarding, an injury that mimics Pop’s leg injury in Vietnam.

Perhaps more damaging, though, is Elliot’s moral injury, which stems from shooting an unarmed civilian Iraqi man. This event becomes a throughline that follows Elliot in all three plays. Hudes relates Elliot’s PTS to both Pop and Grandpop by interweaving their stories through A Soldier’s Fugue; the characters never actually speak to each other onstage but instead often narrate each other’s movements or simultaneously perform the same actions. For example, after their first kill, both Elliot and Pop kneel next to the deceased, grabbing and searching the dead men’s wallets to see photos of their families. The clear suggestion is that these different war experiences are not only strikingly similar but are in some sense transferable. Elliot went to war because Pop went to war like Grandpop before him. Yet none of the male characters ever share their stories with each other. Each man silently endures their trauma. Just as Grandpop’s flute is handed down from Pop to Elliot, so too is their moral injury.

In Hudes’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Water by the Spoonful, which premiered in 2011 at Connecticut’s Hartford Stage, the story picks up six years later, and the scope is broadened. It’s a multilayered story guiding the audience into emotionally dark locations plagued by drug addiction, PTS, terminal illness, divorce, and death. Yet despite the melancholy of her play’s individual parts, Hudes manages to assemble a beautiful mosaic demonstrating the strength of community and human compassion. The central plot line involves the online narcotics anonymous community created by Elliot’s biological mother, Odessa. In this world, we witness the transformative and nurturing power love and understanding have even when mediated through a virtual environment.

Even here Elliot continues to be the seminal character of this family narrative. Due to his persistent leg injury, he has left the Marines and now lives with his parents in North Philadelphia. As if managing his own physical and moral injuries weren’t enough, Elliot is also Ginny’s primary caretaker as she slowly approaches her death. Although he desperately wants to pursue acting, Elliot resigns himself to working at a Subway restaurant to help pay for rent and Ginny’s medication. After Pop notifies him by text that Ginny “is on a breathing machine,” Elliot seeks support from his cousin Yazmin, a recently divorced thirtysomething music professor at Swarthmore.

From the opening scene Hudes reveals that Elliot is still haunted by the ghost of the Iraqi man. Yazmin introduces Elliot to Professor Aman, who is played by the same actor that plays the ghost. Elliot wants Professor Aman to translate the Arabic sentence, “Momken men-fadluck ted-dini gawaz saffari.” We find out that the ghost continuously repeats this sentence when he appears; the ghost is asking for Elliot to return his passport. This relates back to the moment in Elliot, a Soldier’s Fugue when he bends down next to the Iraqi man and takes items out of his pocket. While Hudes does not confirm until The Happiest Song Plays Last, the final play in the trilogy, that Elliot did indeed take the passport, this interaction between Elliot and the ghost establishes the durability of Elliot’s moral injury. Even after six years, Elliot is plagued by hallucinations. Moreover, as the stress in Elliot’s life increases, so too does the intensity of his delusions. Near the end of the play the appearance of the ghost turns into a physical altercation as the ghost desperately reaches for Elliot’s pocket. The two briefly struggle before the ghost pulls Elliot’s wallet from his back pocket and empties its contents in much the same way Elliot did in Elliot, a Soldier’s Fugue.

Apparitions aren’t the only indication of Elliot’s PTS. In one interaction with the narcotics anonymous support group, Yazmin learns that Elliot overdosed on pain medication three times while in the hospital for his leg. While Elliot is not currently abusing prescription medication, Hudes insinuates that he previously resorted to self-medication or possibly suicide so that he could deal with his moral injury.

In the final installment of this series, The Happiest Song Plays Last, Hudes transports the audience two years forward from the funeral for Ginny in Puerto Rico. Yazmin has moved into Ginny’s house and become a matriarchal figure to the entire neighborhood. Meanwhile, Elliot, who decided to move to Los Angeles at the end of Water, is now in the deserts of northern Jordan filming a documentary about the war in Iraq. The movie, titled Haditha on Fire, is based on Battle for Haditha, a film Hudes’s cousin, Elliot Ruiz, filmed in 2007. The Elliot of The Happiest Song appears to have turned a corner in his battle against moral injury. While he still struggles, he realizes he must make peace with his actions. Initially he believes that disposing of the passport will help him forget. But after Elliot is unable to bury the passport in the sand, he asks his friend Ali, an Iraqi cultural advisor on the film, to return it to the dead man’s family. While this attempt also fails, it helps Elliot realize that he must learn to live with his decision. In the end, with the help of his pregnant wife, he plants the passport in Yazmin’s backyard, where the avocados “refuse to grow.”

Despite the tidy wrapping that Hudes gives to Elliot’s story in this play, she advances two very important ideas. First, that people with moral injuries will never be able to undo the events that caused the initial trauma. A moral injury is a transgression against one’s own moral beliefs. Once a soldier commits an act that undermines her/his moral grounding this cannot be reset. As the cliché has it: The only way out is through. By having Elliot bury the passport in the dirt of the backyard, Hudes suggests that Elliot’s moral injury is now part of not only his story but the entire family’s story.

Furthermore, by having Elliot bury it where Yazmin was trying to grow avocados, Hudes suggests that this moral injury can produce something positive for generations to come. Many Puerto Rican families who move to states in the Northern U.S. try to grow avocados, a traditional food, but can’t because of the weather. Elliot’s decision to plant the passport in the backyard signifies that this moral injury will, like avocados, become part of the family heritage—but the avocados can’t grow. This does not mean the family will transgress their moral beliefs, but rather that Elliot’s moral injury will help to guide future generations in his family, including his soon-to-be born son.

In addition to the character-centric implications, Hudes makes a larger statement about moral injuries. Ali writes a letter to Elliot about the son of the man he killed: For eight years the boy has not been able to speak. Neither doctors nor his mother can help him overcome the trauma he witnessed. He has been forever impacted by a decision out of his control. By invoking this child and his trauma, Hudes reminds the audience that despite the difficulties facing Elliot, the family of the man he killed will never be able to replace their loss. While we, as veterans, and as Americans, contemplate and mourn our losses, whether physical or mental, we must always remember the cost to those who had no choice in the war.

Like most other plays written about OIF or OEF in the last decade, Hudes’s main character received his moral injury because he was in combat and killed someone. It is understandable because of her personal relationship with her cousin that she wrote about this experience. It does, nevertheless, belong with the group of plays that only discuss moral injury in terms of direct action in the battlefield. What happens to service members who are not directly “in the fight” but are removed from it through technological advances? Are these veterans at risk for PTS or moral injury?

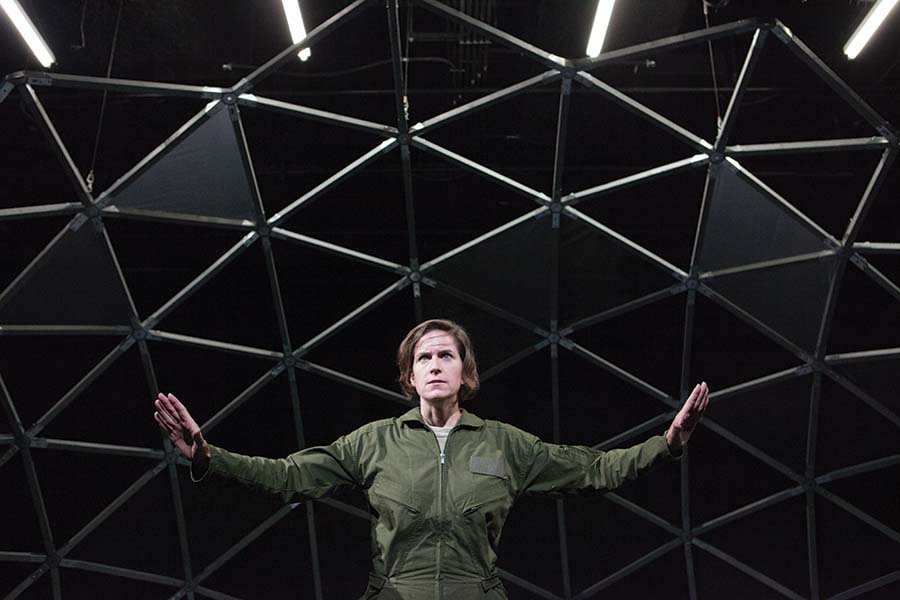

That’s the territory covered in Brant’s Grounded, which tells the story of a highly praised F-16 fighter pilot forced to leave the cockpit due to her pregnancy. After a few years away she decides to return, only to be relegated to a remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) squadron—or, as she derogatorily calls it, the “Chair Force”—in a trailer several miles outside of Las Vegas. As she switches between recollections of sorties over Afghanistan with her new job at a computer monitor, the Pilot struggles to make peace with a surreal new battlefield. For 12 hours a day she hunts down terrorists across the world, making kills with the push of a button. After her shift is over, she returns home to her husband and child without any of the physical remnants of war upon her. Ultimately the Pilot is unable to compartmentalize these parallel lives, as she begins to experience empathy for those on the other side of her screen.

In a world where war fighting is increasingly technological and extrajudicial killings with RPAs are becoming the norm, Brant calls much needed attention to the personal impact this may have on people in our armed forces. At the beginning of Grounded, the Pilot is confident in both her skills and the purpose of her missions. She is seemingly unaffected by the lives she takes when she fires missiles at verified targets. On the other hand, after she accepts her new assignment in the RPA squadron, each confirmed kill weighs heavily on her, until finally she chooses to disobey orders by not firing on a terrorist. In the Pilot’s situation, increasing her proximity to the battlefield—even virtually—has allowed her to view the enemy as a human being rather than as simply a target, as she did previously. From the cockpit of her F-16, it would have been difficult to see the people she was killing; indeed, the Pilot acknowledges that she was “long gone by the time the boom happens.” But sitting in the trailer and shooting targets using satellite imagery means that she can see the results of her actions: One minute she sees a human figure on a computer, the next minute she sees an explosion where the person was standing. The Pilot can no longer ignore the destruction her missiles cause. She must confront them through the gray screen.

In addition to feeling empathetic connections with her targets, the Pilot’s decreased proximity to her home and family make her more susceptible to moral injury. Part of the psychological survival mechanism of military personnel in combat resides in successfully segmenting their lives. This is particularly true when it comes to separating war fighting and family time. During my own deployments, I found it difficult to speak with my wife over the phone or Internet without being temporarily consumed by thoughts of my own mortality or the gravity of being in a theatre of war. But distance made this feeling subside quickly. In the case of RPA pilots, however, that physical distance is removed; they can go home to their family each night after a day at the office. According to an unnamed Air Force drone pilot in an interview with Foreign Policy magazine, war and family “are two very, very different worlds. And you’re in and out of those worlds daily. I have to combine those two worlds. Every single day. Multiple times a day.”

The Pilot in Grounded is unable to maintain psychological distance between the area of operations and her home life. Her two worlds ultimately collide when she is ordered to terminate her target while he is visibly embracing his child, and for a moment the Pilot is unable to distinguish between her target’s life and her own. She superimposes her daughter over the target’s son and is unable to complete her mission. When another RPA pilot steps in to make the kill, the Pilot sees her own daughter dismembered by the missile. As everyone else in the RPA trailer cheers around her, she believes they are cheering for the death of her daughter. The Pilot’s moral injury occurs precisely because of her proximity to home and her family. Far from codifying PTS tropes, Brant’s depiction disrupts common narratives about wartime psychological trauma.

All of the works I’ve discussed represent some of the issues at play for war veterans attempting to integrate into a civilian population that simply can’t understand or relate to combat experiences. Prior to his imprisonment, Cain’s antihero repeatedly wakes up in a jail cell and ends most nights blacking out after heavy drinking. In Hudes’s trilogy, Elliot, who battled an addiction to prescription meds, is now haunted by a hallucination. Over the course of his play, Brant’s Pilot slowly disengages from the family she loves because she can’t separate her combat life from life at home.

Like most other depictions of life after war, however, these stories represent only a minority of veterans. The conversation about PTS and moral injury should continue, but we must also explore other lines of discourse in the representation of war veterans. In the last decade, we saw increased homelessness amongst military veterans; a medical system that failed some of the poorest former service members; the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell; the official acceptance of women into combat roles; transgender people being able to openly serve; and an increasing chasm in communication between the military and civilian worlds. These seem like promising subjects for the stage. We should also see more work about the impact of deployments on the spouses and children of military veterans, not necessarily from the position of PTS but simply due to the long separations. In three years, I saw nine marriages in my company dissolve because of deployments. These issues are as important as PTS, yet they’re relatively unexplored.

Most importantly, we must be nuanced in our representation of the military. Veterans in America are typically valorized, victimized, or demonized. I would settle for our lives being dramatized.

Bart Pitchford is a researcher, freelance writer, sound designer, artist, military veteran, and activist. During his eight years in the U.S. Army, he deployed as a Psychological Operations Sergeant to Iraq, Yemen, and Pakistan. He is also a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, and his dissertation focuses on performance and citizenship of displaced Syrians living in Jordan.